THE POLITICS OF ILLINOIS from the 1830’s to 1850’s can provide a good case study of attitudes toward gays—partly because the region was then a part of the American West, where political discussion was almost unrestrained, and partly because participants included some of the most famous characters in American history.

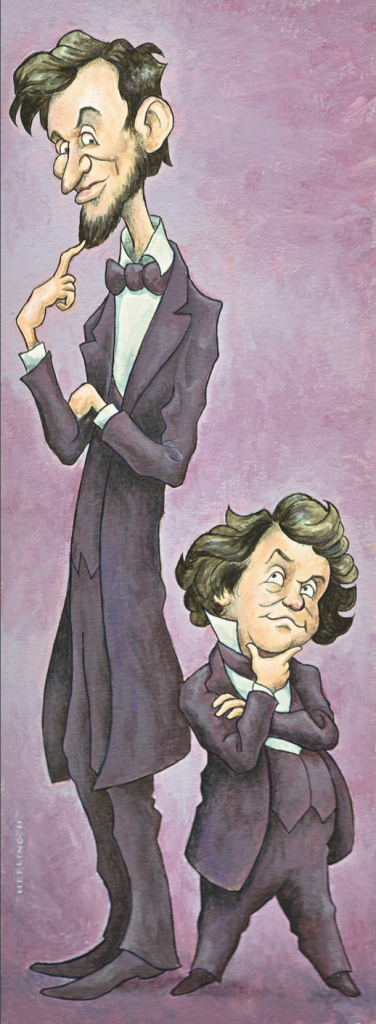

Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln’s famous political adversary and debating opponent, could be quite uninhibited in public in his physical contact with men. A friend noted that soon after Douglas won election to the Illinois state legislature, he “in so short a time made himself acquainted and familiar with the members of the legislature, and had become quite a pet with them, sitting on their knees even.” Another politician later observed that after Douglas became a judge, “It was not unusual for him to come down from the bench, or leave his chair at the bar, and take his seat on the knee of a friend, and, with an arm thrown familiarly around the neck of his companion, have a social chat, or a legal or political consultation.” An eyewitness watched Judge Douglas routinely descend from the bench while a case was underway and go over to lawyers, “often sitting in their laps.” Someone who casually knew Douglas recalled, “He has been seen at Knoxville, when the court room was crowded, to seat himself upon the knee of old Governor McMurtry and, with his arm upon his shoulder, talk with him for a considerable time.”

Social customs change, and such lap-sitting per se isn’t necessarily evidence of erotic or tactile pleasure, but in this case we have the recollections of Douglas’ contemporaries—their startled confusion—to justify our own hunch.