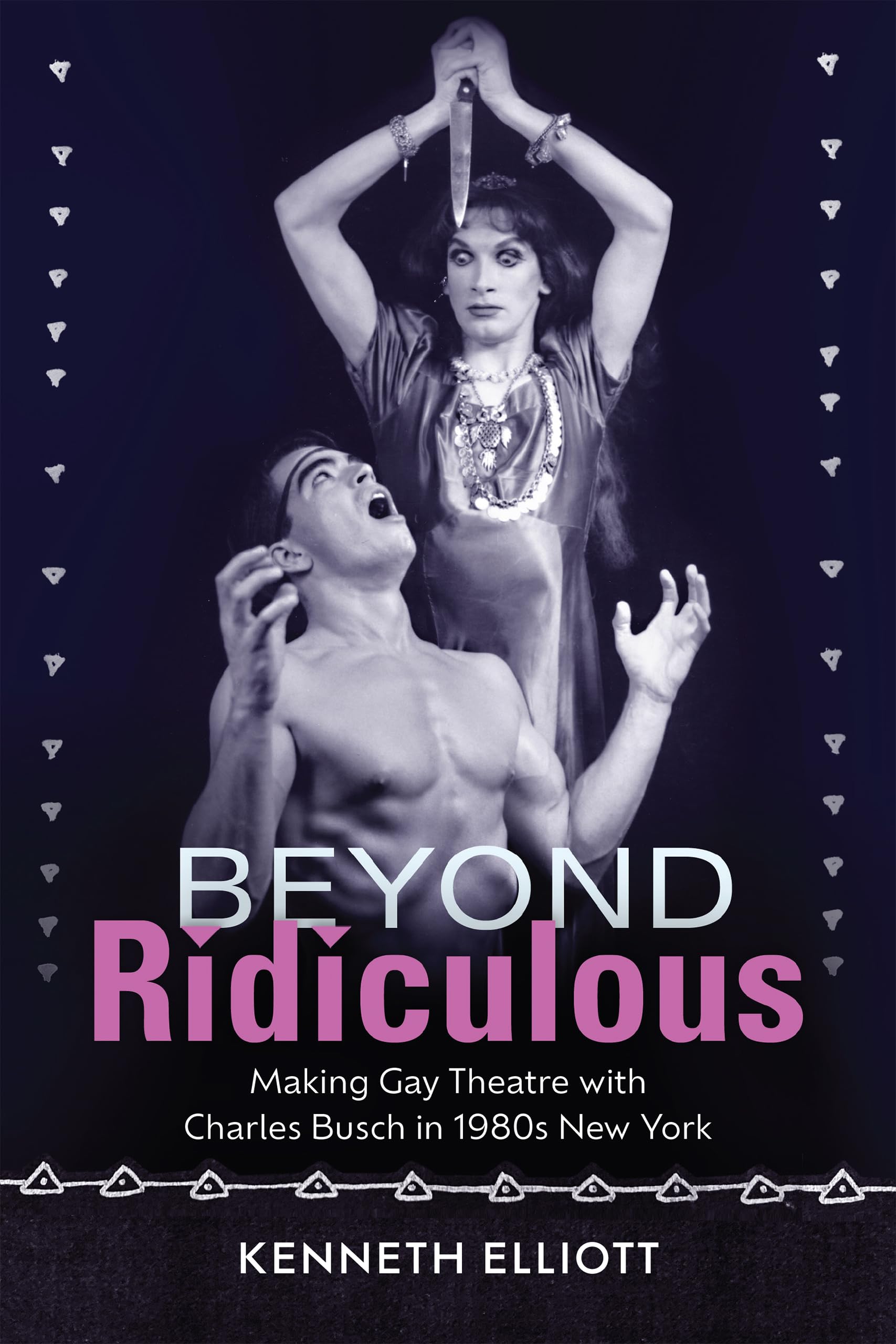

BEYOND RIDICULOUS

BEYOND RIDICULOUS

Making Gay Theatre with Charles Busch in 1980s New York

by Kenneth Elliott

Univ. of Iowa Press. 194 pages, $35.

CHARLES BUSCH’S landmark plays for the Theatre-in-Limbo (1984-1991) were the product of a very particular yet short-lived cultural moment, the final flourishing of the Theater of the Ridiculous movement that goes back to the mid-1960s and is most closely associated with Charles Ludlam. It was as though, from the mid-1970s through the mid-’80s, the political intensity of the Gay Liberation movement could be relaxed as gay people playfully, and in some cases tauntingly, exposed the absurdity of the most oppressive conventions of heterosexual culture.

As Kenneth Elliot reports in Beyond Ridiculous, his history of Busch’s company, the name Theatre-in-Limbo (“hyphenated like Stratford-upon-Avon”) was derived from the makeshift space where they produced their first plays. The Limbo Lounge was an art-gallery-cum-performance-space-cum-unlicensed-after-hours-club on East 10th Street in the heart of Alphabet City. (It later moved to a vacant garage on East 9th, which was a larger but more awkwardly configured space.) The very word “limbo” suggests the marginal quality of these productions, which invited audiences to delight in well-known cinematic formulas even as the plays undercut their triteness, and which were never more serious than in their determination to have fun. A mad exuberance and raw creativity enlivened Busch’s initial productions, notably Vampire Lesbians of Sodom, Theodora, She-Bitch of Byzantium, Pardon My Inquisition, and Gidget Goes Psychotic. Audience members were crammed into a cramped space and seated on the floor, a veritable purgatory.

Busch starred in a series of female parts. But unlike Charles Pierce’s over-the-top impersonations of Bette Davis, Tallulah Bankhead, Carol Channing, Katherine Hepburn, and Mae West, which became so popular that Pierce became something of a fixture on 1980s television, and—unlike Charles Ludlam, whose plunging bodice revealed his hairy chest when he played Camille—Busch evolved into a sensitive portrayer of women on stage, especially as he parodied B-movie conventions. The Lady in Question, in which an actress visiting an alpine village becomes a heroic member of the Nazi resistance movement, was conceived in part as the opportunity for Busch to wear an elegant, full-skirted green satin dress that he’d fallen in love with and sought to create a heroine worthy of wearing. Busch’s ability to play female parts proved so convincing that he dared to do so before the movie camera, under the harsh glare of production lights, in Psycho Beach Party and Die, Mommie, Die!

Unfortunately, Theatre-in-Limbo’s moment in the sun was cut short by two phenomena. The first was the commercialization of the East Village as speculators began gobbling up the Village’s relatively cheap real estate, depriving Off-Off-Broadway performance artists of the makeshift spaces in which they thrived. Elliot, the company’s astute business manager (as well as the plays’ director and Busch’s leading man), secured the lease on the historic Provincetown Playhouse, which allowed the company to move from Off-Off-Broadway to the more legitimate Off-Broadway, generating higher visibility for their productions. (The transferred production of Vampire Lesbians of Sodom ran for over 2,000 performances.) The downside was a less spontaneous audience of tourists in search of “an authentic Greenwich Village experience” and up-towners exploring the avant-garde chic of theaters south of Union Square. Busch’s plays became more plot-driven and less flamboyantly campy. (In Red Scare on Sunset, for example, Busch played a movie actress whose husband has been coopted by a communist cell in Hollywood.) Inevitably, the company lost the improvisational energy that came from engaging directly with an audience seated only a few feet away and with whom the actors rubbed shoulders in the building’s only bathroom, which sometimes served as the performers’ dressing room as well.

Second, even though the “Limbo” was founded during the early AIDS years, the crisis as it escalated caused audiences to reconsider how apolitical their fun could afford to be. (Founding company member Bobby Carey succumbed to the disease. He was a physically alluring young man whom Busch invariably found a way to bring on stage naked.) But this is not to say that the epidemic killed gay theater. Paradoxically enough, AIDS helped make gay theater commercially viable. Playwrights like Larry Kramer, Terrence McNally, William Finn, and Tony Kushner scored Off-Broadway and Broadway triumphs with plays that a decade earlier might have been consigned to Off-Off Broadway. But Busch’s form of satire did not seem able to make the leap to address a bona fide health care crisis. (Imagine him as Rosalind Russell’s Sister Kenny resolving to find a treatment, not for polio, but for AIDS.)

Instead, Busch went on to write a successful but more conventional comedy, The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife (2000), which became an excellent vehicle for Linda Lavin, rather than Busch himself, as a self-indulgent, upper-middle-class woman undergoing a midlife crisis. His more recent efforts—like Shanghai Moon and the current Ibsen’s Ghost—costar commercially successful actors like B. D. Wong and Thomas Gibson, suggesting the extent to which Busch is no longer in limbo, but has moved on to more mainstream success.

Elliott’s history of the Theatre-in-Limbo is less a study of the company’s contributions to the development of gay theater than an eyewitness account of Off-Off-Broadway’s last hurrah. Let it serve an an antidote to Busch’s fictionalized account of the company in Whores of Lost Atlantis (1993), which tried so hard to capture the screwball antics of those early performances that it fell horribly flat. Nevertheless, taken together the books might help explain why, like the legendary Camelot, the Theatre-in-Limbo burned so brightly but for such a short period of time.

Raymond-Jean Frontain is professor of English at the University of Central Arkansas and editor of the academic quarterly ANQ.