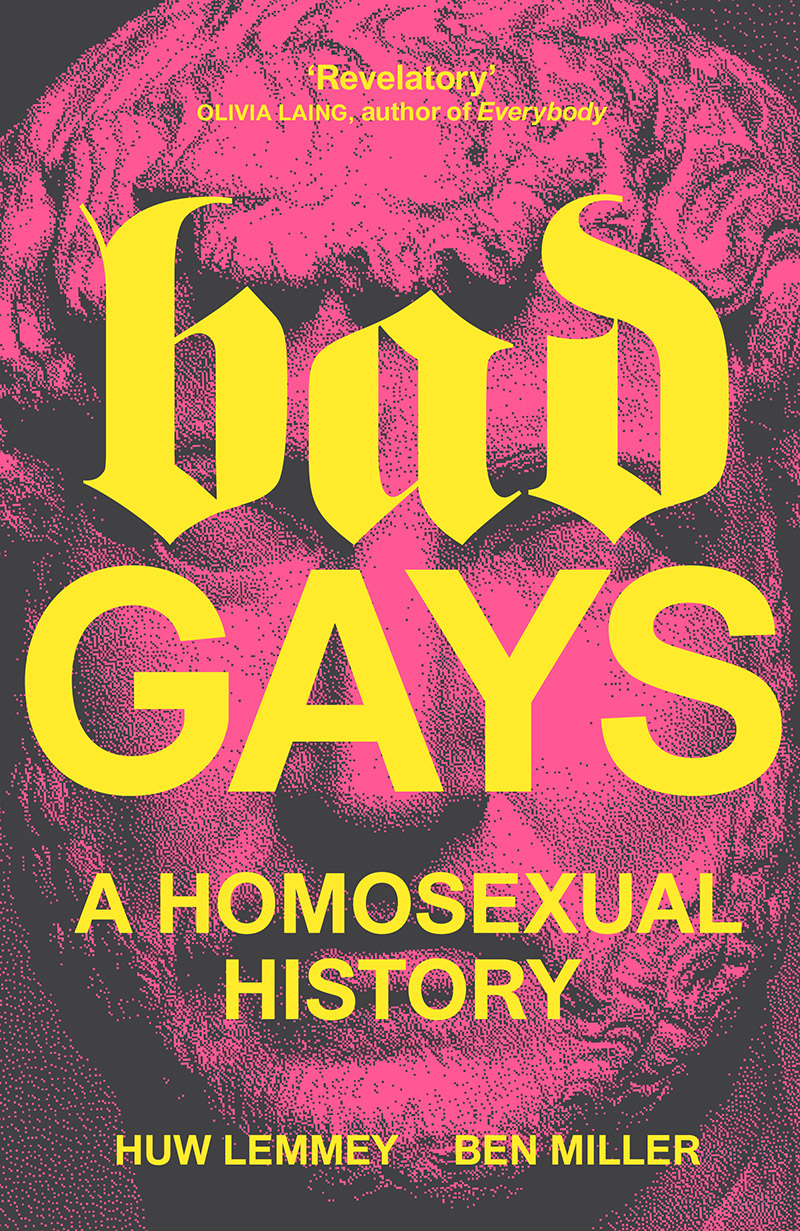

IN THEIR INTRODUCTION to Bad Gays: A Homosexual History, authors Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller illustrate one of their central arguments with a trenchant contrast. Oscar Wilde has emerged as one of the key figures of the contemporary LGBT rights movement, they point out, as he “was one of the first men in British society to give a creative form to a sexuality that barely yet understood itself,” and they agree that he earned this place.

But what about his lover, Lord Alfred Douglas, better known by his nickname “Bosie”? Just as Wilde had contributed to what was emerging as a new identity and had created something akin to a rallying cry for a century of queer activism that would follow, Bosie could be thought of as sheer “evil twink energy” (the first of many such biting epithets used by the authors). While largely forgotten in the history books, Bosie emerged as viciously anti-leftist, anti-Irish, and anti-Semitic. He would even accuse Winston Churchill of being caught up in Jewish conspiracies during World War II. Churchill would successfully sue Bosie, who died broke, and only two people attended his funeral.

It’s a provocative argument, one they put forth in a way that’s both thorough and entertaining. Why, they ask, have so many historical gays close to power gone so wrong? As they put it, “When a gay man becomes a fascist, how does his homosexuality affect his attraction to the politics of venerating the state as though it were a go-go boy dancing on a box?” Questions about power, corruption, and repression make up the bulk of this book, which is a who’s who of queer nasties through history. Some of the subjects are obvious—J. Edgar Hoover and Roy Cohn, for example—but I was less familiar with the antics of Victorian sex worker Jack Saul. Their conclusions about how Margaret Mead’s sexuality informed her research are worth reading. The final chapter, on Dutch politician Pim Fortuyn, who embraced Islamophobic anti-immigrant rhetoric before being murdered in 2002, is the most captivating entry in the book, given its relevance to our current political malaise.

With each chapter standing on its own—presumably an artifact of the book’s origin as a podcast—an overarching argument can seem elusive. But that could also be seen as a virtue, as it allows for a more casual style of reading. The writing style is conversational, so it can seem like chatting with an enthusiastic academic who’s equally comfortable analyzing Virginia Woolf or passing celebrity gossip. I was horrified at some revelations and laughed out loud at others.

It’s impossible to be comprehensive in a book such as this, but some of the omissions were surprising. I wondered why there was no chapter on Leopold and Loeb, the child-murdering duo who killed a fourteen-year-old boy and almost got the death penalty (but were spared when their attorney, Clarence Darrow, introduced Freudian experts who shifted the blame to their upbringing). But this is a minor complaint. Bad Gays is a memorable book, one that I’m still pondering months after finishing it. Lemmey and Miller have reminded us of how incomplete and arbitrary our history can be.

Matthew Hays teaches film studies at Concordia University, Montréal.