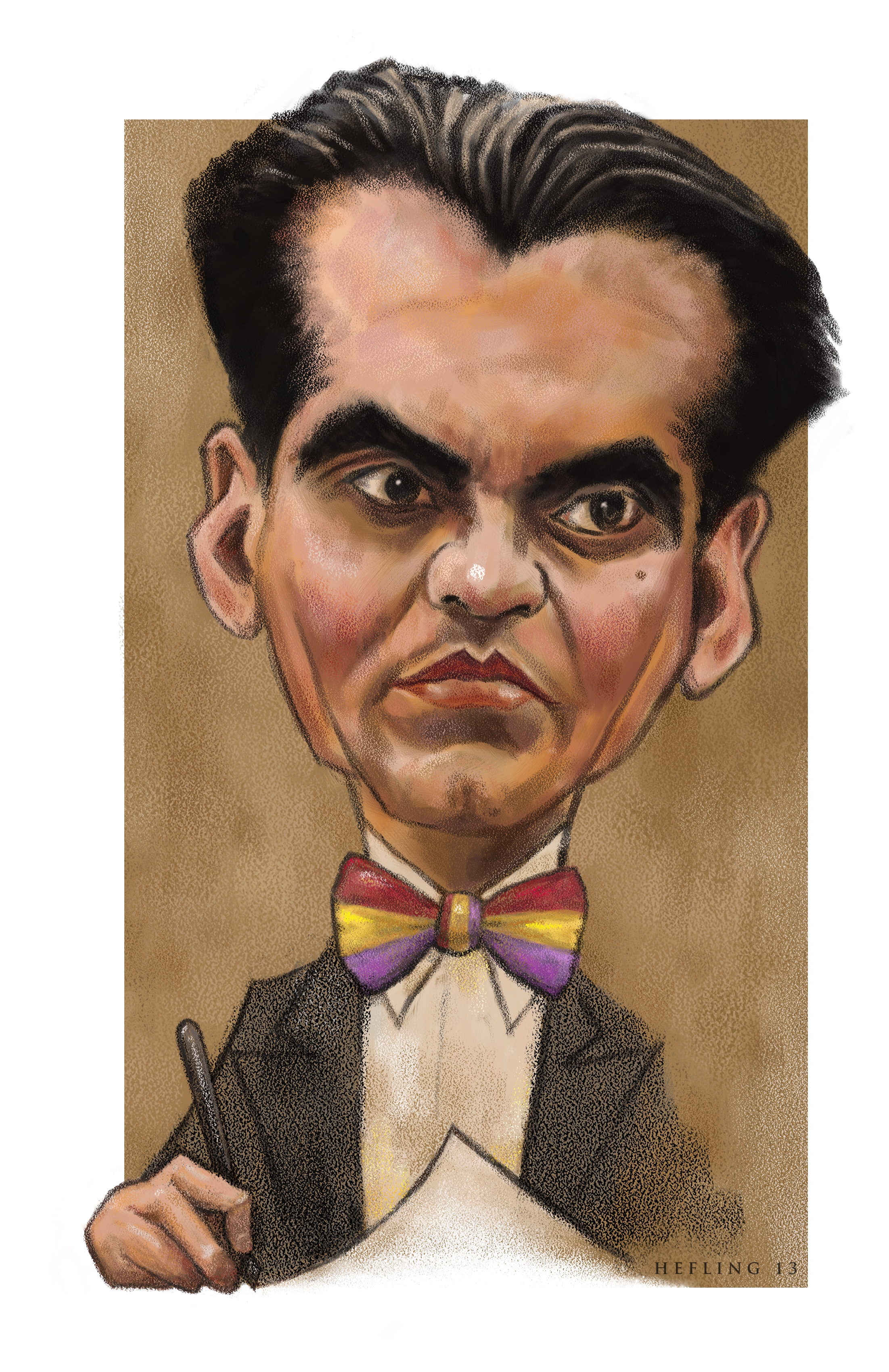

WHEN Spanish poet Federico García Lorca and American student Philip Cummings first met and became lovers in Madrid in July 1928, they had no idea that their brief liaison would evolve into an intimate relationship that spanned two continents and almost three years. Despite their disparate backgrounds and ages (Lorca was thirty, Cummings 21), they had much in common: both were charming extroverts who shared a love of music, literature, and all things Spanish. But while Cummings had just begun composing verses, Lorca was already Spain’s best-known young poet, destined to achieve lasting international fame for his much-loved poems and plays.

In June 1929, a year after meeting Cummings, Lorca traveled from Madrid to New York City with the stated intent of learning English. He dutifully enrolled in a summer language course at Columbia, but skipped most of his classes and explored the city instead. When the course ended in mid-August, he took an overnight train from New York to northern Vermont at the invitation of Cummings, a native Vermonter. There, in the tiny village of Eden Mills, he joined Cummings at a rustic cottage beside Lake Eden that Cummings had rented for the month of August. Although Lorca spent only ten days at the lake with Cummings, his time in Vermont had a profound effect on both his poetry and his personal worldview.

While Lorca and Cummings were not alone at the cottage—Cummings had invited his parents, aunt, and cousin to stay there as well—they had ample opportunity to continue their affair without fear of discovery. With Spanish serving as their own private language, they could say whatever they wished without arousing suspicion. With not enough bedrooms to go around, they were happy to share a private sleeping porch. And, as the favored young men of the household, they could take off on their own whenever they wanted for as long as they wanted, and no one gave it a second thought.

During and immediately after his stay at Lake Eden, Lorca composed a series of eight poems that reflected his Vermont experiences and his changing feelings toward Cummings. These poems later formed a core component of his landmark collection, Poet in New York. In fact, the Vermont poems make up almost one-quarter of the work, despite its city-centric title. Yet even today, the full story of Lorca’s intimate relationship with Cummings, and the poems it inspired, is almost unknown.

It may seem strange that such a pivotal episode in Lorca’s emotional life was overlooked for so long, especially since his romantic affairs have long been of interest to scholars and biographers. But this omission was not an accident. It was instead one of many repercussions of Lorca’s tragic execution at age 38 by Franco sympathizers in August 1936, at the start of the Spanish Civil War. In the chaos that followed, a small group of Spanish faculty members at Columbia University took on the task of helping Lorca’s family promote and protect his literary legacy. As part of this effort, they adopted a strict code of silence, actively suppressing any information that hinted at Lorca’s homosexuality. Since they had reason to suspect that Lorca and Cummings were lovers, they made a conscious decision to treat Lorca’s visit to Vermont as a meaningless side trip, and to dismiss Cummings as an inconsequential person in the poet’s life.

The primary spokesman for this group was Dr. Ángel del Río, a professor of Spanish literature at Columbia from 1929 until his death in 1962. During Lorca’s time in New York, Del Río served as host, guide, and guardian for the poet, whom he had met in Madrid a few years before. In this capacity, Del Río escorted Lorca to Grand Central Terminal in August 1929 and helped him board the train to Vermont. Most importantly, when Lorca’s stay in Vermont ended, he went directly to a summer boarding house in the Catskill Mountains to spend three weeks with Del Río, his wife, and their infant son. Considering the close friendship between the two men and the emotional turmoil evident in his poems of the period, Lorca would surely have unburdened himself to Del Río about at least some aspects of his relationship with Cummings.

After Lorca’s untimely death, whatever Del Río said or wrote about the poet’s life, particularly his New York period, was considered the authoritative word on the subject. Del Río never met Cummings and bore him no personal ill will. The decision to erase Cummings and Vermont from the official version of Lorca’s life story was simply a casualty of the more pressing need to deflect attention from the poet’s sexual orientation. And perhaps Del Río and his colleagues were right. Perhaps Lorca’s poems and plays would be unknown to us today if his homosexuality had become public knowledge, causing publishers and scholars to steer clear of his work. Consider, for example, the alarm expressed by biographer Mildred Adams in 1971 upon hearing “certain unpleasant rumors” about Lorca’s lifestyle. Adams was a well-educated, well-traveled journalist who had known Lorca personally, and even she seemed dismayed at the thought that he might have been gay.

For his part, Del Río avoided mentioning the Vermont visit for as long as he could. In 1941, he went so far as to censor a letter that Lorca had sent him from Eden Mills, deleting a sentence related to Cummings, before allowing it to be published. The offending sentence, discovered by Christopher Maurer and Andrew A. Anderson, reads: “My young friend Cummings translates my songs and looks at me with the tenderness of a wounded cow.” Del Río apparently decided that any mention of tender glances, particularly in connection with Cummings and Vermont, was simply too hazardous to include.

When it was no longer possible for Del Río to pretend that he knew nothing at all about the Vermont episode, he said as little about it as possible. In 1955, he finally identified Cummings (by last name only) as Lorca’s host in Vermont. However, he still professed privately not to know whether Cummings was a real person or a figment of Lorca’s lively imagination.

Just as Del Río intended, the true nature of Lorca’s relationship with Cummings remained secret for a full fifty years after the poet’s death. It was Cummings himself who eventually came clean. He had married in 1938, fathered two children, and become a successful public speaker and news analyst. However, according to his family and the son of one of his longtime partners, he also used his frequent work-related trips to pursue sexual relationships with other men. Cummings longed to tell the world about his intimate activities with Lorca, but he had his own reputation to protect and could not bring himself to go beyond broad hints to a few researchers. Not until 1986, after his wife had died and he was in failing health, did Cummings finally reveal the whole truth to Spanish poet Dionisio Cañas. Unfortunately, by then almost no one was listening.

Just as Del Río intended, the true nature of Lorca’s relationship with Cummings remained secret for a full fifty years after the poet’s death. It was Cummings himself who eventually came clean. He had married in 1938, fathered two children, and become a successful public speaker and news analyst. However, according to his family and the son of one of his longtime partners, he also used his frequent work-related trips to pursue sexual relationships with other men. Cummings longed to tell the world about his intimate activities with Lorca, but he had his own reputation to protect and could not bring himself to go beyond broad hints to a few researchers. Not until 1986, after his wife had died and he was in failing health, did Cummings finally reveal the whole truth to Spanish poet Dionisio Cañas. Unfortunately, by then almost no one was listening.

Because the underlying facts about Lorca’s relationship with Philip Cummings were suppressed for so long, Lorca scholars and biographers continued to assume that the two were just casual acquaintances. A few of them, notably Daniel Eisenberg, Ian Gibson, and Leslie Stainton, made valiant attempts to document how Lorca and Cummings spent their time together at Lake Eden, but many important details were missed or simply unavailable at the time. And since no one knew that they had been lovers, no one wondered how their relationship might have influenced Lorca’s Vermont poems, or how their shared experience of being young homosexual men in an unforgiving world might have shaped their private conversations.

CONSIDER, as a case in point, how hearing the poems of Walt Whitman for the first time, as translated by Cummings, may have affected Lorca. By the late 1890s, Whitman’s unabashed celebration of love between men in Leaves of Grass, his magnum opus, had given him almost iconic status among English-speaking gay men. According to literary critic Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, anything to do with Whitman—photographs of the poet, gifts of his books, specimens of his handwriting, news about him, or admiring references to him—could serve as a secret signal between men seeking other men as partners.

For gay men, the most important and meaningful poems in Leaves of Grass were found in the section, or “cluster,” that Whitman titled “Calamus” after a common wild reed (Acorus calamus, also known as Sweet Flag) with an unmistakably phallic flower stalk. The “Calamus” cluster consisted of 45 poems that praised both comradeship and romantic love between male companions—not only in the abstract, but also as an ingredient of Whitman’s own personal life. And while the homoerotic aspect of Whitman’s poetry was virtually ignored by scholars and critics for decades, it was unmistakable to gay male readers.

As a result, Whitman himself became a cherished role model for young men struggling to understand and accept their homosexuality. He served as a source of comfort, hope, and affirmation in their lives, as well as an imagined, accepting father figure. The diary entries below, for example, were written in the 1920s by a young gay resident of the District of Columbia:

July 5, 1923: I walked home rather happily and settled into my leather-seated rocker and read in “Calamus”— the heart of Leaves of Grass. What a noble, lovable man old Walt was! And he was a government clerk too, like myself. Often, I yearn toward Walt as toward a father, look up at his picture, then close my eyes and feel him beside me, rugged and strong with his gentle hands caressing and comforting me.

December 9, 1929: Walked home deeply wretched. Got out my Whitman and read all of “Calamus.” It seems that all my strength and vitality have gone toward loving Dash.

August 25, 1930: Tonight is the anniversary of the first sexual experience I ever had—with Randall, ten years ago. It was then that I thought I had finally joined forever with a loving friend and companion. I still cherish the memory of that beautiful moonlit night. No matter what happened afterward, “that night I was happy.”

The quoted phrase in the last entry is from the poem “When I Heard at the Close of the Day,” which had particular resonance for many gay men. In it, Whitman described the elation he felt at his lover’s return after a long absence, leaving no doubt about the gender of his beloved. The last two lines read in full: “In the stillness in the autumn moonbeams his face was inclined toward me,/ And his arm lay lightly around my breast—and that night I was happy.”

Spanish poet and translator León Felipe has long been credited with introducing Lorca to Whitman’s work, but evidence suggests that Lorca’s first exposure was actually with Cummings. The following entry from the journal Cummings kept during their time together at Lake Eden indicates that he brought a copy of Leaves of Grass with him to the cottage and shared it with Lorca:

The lake was rough-shod this afternoon and the gusts of wind swept in on us, lying beside a big log, and trying to understand the infinite beauty of Whitman. Where better could we enter into a familiar companionship with this great Interpreter than in the outdoors of a mountain landscape? The storm clouds and the wind movement gave a scenic background, making a living vitaphone of the words of our great Walt.

We are all so prone to discuss the work of the day, the sunset, the storm—everything which has particularly moved us, in the terms: “If I could only put that on paper!” Whitman has put it all down for all of us. He has grasped a whole humanity and made significant gestures at those forbidden subjects which we usually cast aside as “quite beyond us”—a sort of mental shrugging of the shoulders on our part. Nothing seems to have been beyond the pen of Walt Whitman, though he may only have touched some subjects in a curious reverent mood.

It is unlikely that Lorca was already familiar with Leaves of Grass, since little of Whitman’s work was available in Spanish at the time, and Lorca knew almost no English. Cummings, serving as both curator and translator, would almost certainly have begun with the “Calamus” cluster—the very poems that addressed the “forbidden subjects” he noted in his journal and which he knew would be of greatest interest to his friend. It must have been a slow process, with Cummings translating line by line, perhaps pausing to point out each reference to a male lover or praise for the male physique. How amazed Lorca must have been to discover that one of America’s most revered poets had written openly and honestly about his attraction to other men, and not been shamed, shunned, or imprisoned because of it.

While we have no proof that Cummings translated the “Calamus” poems for Lorca at Lake Eden, some of Lorca’s Vermont poems appear to reflect, at least in part, the tone and content of Whitman’s work.* Consider, for example, Whitman’s “In Paths Untrodden,” the first “Calamus” poem and a harbinger of those that follow. The poem is almost a manifesto, a declaration that the speaker is finally ready to reveal an essential truth about himself that he has hesitated to state openly in the past. Its intimate, first-person voice is characteristic of many of Whitman’s poems, and we are clearly intended to conclude that the speaker is Whitman himself, given that he even tells us his age.

In paths untrodden,

In the growth by margins of pond-waters,

Escaped from the life that exhibits itself,

From all the standards hitherto publish’d—from the pleasures,

profits, conformities,

Which too long I was offering to feed my Soul;

Clear to me, now, standards not yet publish’d—clear to me

that my Soul,

That the Soul of the man I speak for, feeds, rejoices in comrades;

Here, by myself, away from the clank of the world,

Tallying and talk’d to here by tongues aromatic,

No longer abash’d—for in this secluded spot I can respond

as I would not dare elsewhere,

Strong upon me the life that does not exhibit itself, yet

contains all the rest,

Resolv’d to sing no songs to-day but those of manly attachment,

Projecting them along that substantial life,

Bequeathing, hence, types of athletic love,

Afternoon, this delicious Ninth-month, in my forty-first year,

I proceed, for all who are, or have been, young men,

To tell the secret of my nights and days,

To celebrate the need of comrades.

There are intriguing parallels between “In Paths Untrodden” and Lorca’s “Double Poem of Lake Eden,” one of the best-known poems from his Vermont period. It may be Lorca’s most deeply personal work, a pure cry from the heart. It projects a level of pain, anguish, and frustration that is absent from Whitman’s poem, but the two share several common threads. These include a strong sense of place, a promise to speak truthfully, and a clear correspondence between the speaker of the poem and the poet himself. The last six stanzas of the poem, below, are from the translation by Greg Simon and Steven F. White:

But I want neither world nor dream, divine voice,

I want my liberty, my human love

in the darkest corner of the breeze no one wants.

My human love!

Those sea-dogs chase each other

and the wind lies in ambush for careless tree trunks.

Oh, voice of before, let your tongue burn

this voice of tin and talc!

the way children cry in the last row of seats—

because I’m not a man, not a poet, not a leaf,

only a wounded pulse that probes the things of the other side.

rose, child, and fir on the shore of this lake,

to speak truly as a man of blood

killing in myself the mockery and suggestive power of the word.

No, no, I’m not asking, I’m telling you what I want,

my liberated voice lapping at my hands.

In the labyrinth of folding screens my nakedness receives

the punishing moon and the clock covered with ash.

I was speaking that way.

I was speaking that way when Saturn stopped the trains

and the fog and Dream and Death were looking for me.

Looking for me

where cattle with little feet of a page bellow

and my body floats between contrary equilibriums.

At first glance, the poem seems almost surreal, dense with images meaningful only to the poet himself. However, once we learn that Lorca did his writing seated alone by the lake, using an overturned boat as a writing desk, we can link several of the poem’s elements to the actual place where it was composed. It is striking how Lorca seems to mirror, then expand upon, the confessional and declarative tone of Whitman’s poem. Whitman’s speaker vows to talk openly and honestly about those he loves, and Lorca’s speaker does the same (“I want … to speak truly as a man of blood”). But Lorca’s speaker goes further, demanding that the reader, and society at large, acknowledge the validity of his emotions and desires—a demand that Whitman never felt compelled to make.

Another commonality is the decision made by both poets to identify himself with the speaker of the poem. For Lorca, in particular, this was a marked departure from the more removed, neutral persona he normally adopted. Perhaps emboldened by Whitman’s directness, Lorca even included his full name in the ninth stanza of his initial version of “Poema Doble”: “I want to cry saying my name,/ Federico García Lorca, on the shore of this lake.” Lorca gave Cuban editor Juan Marinello a copy of the poem with the wording shown above in the spring of 1930, but his boldness did not last. Shortly thereafter, he revised the second line to read “rose, child, and fir on the shore of this lake.”

Lorca’s struggle to decide how much to reveal about himself in his work continued long after his stay at Lake Eden, but Whitman’s poems may at least have allowed him to rethink what was possible. Despite the deep anger and sadness he felt at the injustice of his situation, Lorca may have found new hope that a homosexual poet could write honestly about his relationships with other men without destroying his literary reputation. Sadly, his life was ended long before he could fully explore this possibility.

It has been ninety years since Lorca and Philip Cummings spent ten days together at a lakeside cottage in northern Vermont, but only now is the full story of their relationship coming to light. Looking back, we may be tempted to criticize the deliberate efforts to suppress the truth about both men as individuals and as a couple. Fortunately, the time when such efforts can succeed has passed. Looking forward, we can anticipate new insights into this important voice of the early 20th century as additional facts, clues, and connections are revealed.

References

Cummings, Philip. “August in Eden.” In Songs, by Federico García Lorca, edited by Daniel Eisenberg, translated by Philip Cummings. Duquesne University Press, 1976.

García Lorca, Federico. Poet in New York. Edited by Christopher Maurer, translated by Greg Simon and Steven F. White. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

Manrique, Jaime. Eminent Maricones: Arenas, Lorca, Puig, and Me. University of Wisconsin Press, 1999.

Russell, Ina, ed., Jeb and Dash: A Diary of Gay Life, 1918-1945. Faber and Faber, 1993.

__________________

* It should be noted that Lorca also wrote a poem titled “Ode to Walt Whitman,” where his interest in Whitman is explicit. Here the speaker decries the flamboyant decadence of the homosexual demimonde he sees around him and commends Whitman’s praise for unpretentious, more masculine partners. However, Lorca did not write his “Ode” until several months after he left Vermont and returned to New York, by which time he had drawn his own conclusions about Whitman.

Patricia A. Billingsley, a biographer based in Williamsburg, Massachusetts, is writing a book about Lorca’s time in Vermont and his relationship with Philip Cummings.