IN THE EARLY 1980s, I began to patronize a gym at the University of Toronto. The locker room proved interesting. The young men seemed proud of their bodies, and normally walked totally naked to and from the showers, a towel slung casually over the shoulder. It was clearly a badge of healthy masculinity to feel comfortable in one’s birthday suit.

If I remember correctly, it was in the late 1990s when first I noticed a significant change in locker-room behavior. To put it succinctly: young, presumably heterosexual men stopped showering together, and have never gone back. Today, if they do shower, they make sure to walk from their locker to the showers with a towel wrapped securely around their middle. Then they make use of the private shower stalls—a fairly recent amenity, apparently installed for reasons of modesty. At my gym, there is still a communal shower option, but I see guys patiently waiting for an unoccupied private stall, even though there are plenty of communal showerheads available. But more typical nowadays are locker rooms with separate shower stalls with curtains or doors as the only option, with no communal showers at all.

At the gym, most men under 45 no longer take off their undershorts when they change into gym clothes, and vice versa, no matter how sweaty their underwear has become. Not showering means that they often leave the gym covered in sweat—in a climate where the mercury hits 95 degrees in summer and descends to minus five in winter. To deal with the attendant odor from working out, they douse themselves in deodorant, if necessary from head to foot. This seems a high price to pay to avoid displaying their private parts in front of their fellow males.

To be sure, a few men still use the showers, which of course requires stripping. And swimmers must strip in order to get into their trunks. But to prepare for either destination, they enact what has been described the “towel dance,” wrapping a towel around the waist, removing their underpants beneath the towel, and putting on their bathing suit or workout trunks before dropping the towel. (The process is reversed when the swim or workout is over.) This is not an easy maneuver to execute, and I’m amused to watch these guys struggle not to fall over just to keep the towel in place. Those bold enough to dispense with the towel turn their backs to face into their locker as they furtively whip off their towel and pull on their trunks.

Asking gay friends about other gyms in town, I’ve heard that these practices are fairly widespread. Indeed they seem to be the norm in both Canada (or at least anglophone Canada) and in the U.S. Some American men have told me that it’s still common for straight men to shower, but that the shift to private stalls is the norm—along with performances of the “towel dance” before and after showering. Why there might be a difference between shower practices in the U.S. and Canada is anyone’s guess, and there may be regional differences in both countries of which I am not aware. But the trend toward extreme modesty—the shift away from male nudity in public places in general—has been widely observed. And it represents a fairly radical departure from norms that have governed male nudity in most Western societies for many hundreds or thousands of years.

The question of why this revolution has occurred is certainly of great interest, and I’ll try to tackle it later on. But first let me try to establish the point that male nudity in public—especially in the presence of other men—has been an accepted practice through the ages.

Men Bathing Together in Western Art

For millennia in European societies, men have never hesitated to strip in front of other men to wash, bathe, or swim. It was only in the 19th century that the bathing costume was invented to allow men and women to swim together—which itself marked a significant socio-sexual revolution.

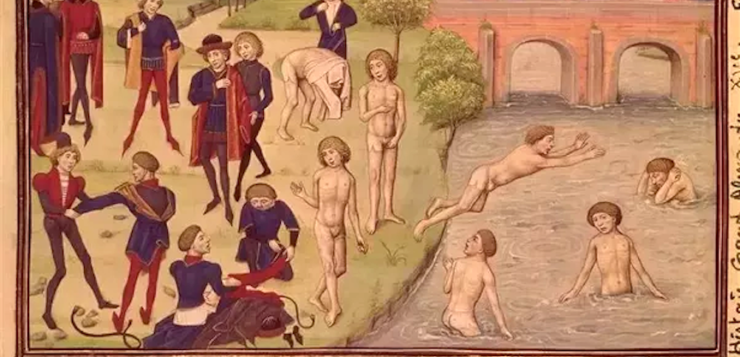

The phenomenon of nudity in all-male settings is widely documented in ancient Greece and Rome. The ancient Germanic peoples as well, according to Tacitus, took a very casual view of male nudity. The fall of Rome and the ascent of Christianity, which is not normally thought of as friendly toward nudity, undoubtedly put a damper on many sexual practices, but there was never any particular taboo on nudity among males (unlike in many Islamic cultures). Even the highly Christianized medieval world tended to be quite “earthy” in matters of everyday conduct. Male nudity was treated as unremarkable, provided no women were present, in activities such as bathing and swimming. We can see an example of this in the early 15th-century illuminated manuscript known as the Très riches heures of Jean, Duke of Berry (see page 16). In the background, male peasants halt their hard work to cool themselves with a swim in a stream, stripping naked to do so—presumably a perfectly typical event during harvest.

And it wasn’t only peasants who swam together nude, or virtually nude, in the 15th century, as we can see in an image from another French illuminated manuscript (page 17). Although these upper-class males do not doff their underwear, it is so skimpy that, especially when wet, it would have left little to the imagination. It is also possible that the artist clothed the swimmers in undershorts contrary to actual practice, for reasons of pictorial decorum. After all, who in real life would have wanted to pull dry hose over wet underwear after a swim?

Moving forward a few centuries—but still in a rather puritanical age—another example of male nudity as an everyday occurrence may be seen in an 18th-century painting by Claude-Joseph Vernet (page 17). Here we see men stripping and swimming in a surprisingly crowded setting, complete with women not too far away. No one seems to notice or care what the swimming men are up to, so matter-of-fact is their presence in a painting that’s mostly about the fine people on the promontory and the busy world over which they preside.

Most readers will be familiar with the famous 19th-century painting The Swimming Hole (1885), by the U.S. artist Thomas Eakins (1844–1916). The ease of these young men in their nudity is evident. No one who viewed this painting when first exhibited, or for many decades thereafter, would have found anything unusual in this scene, and it was not regarded as homoerotic. It wasn’t until the 1970s that art critics began to postulate a such an element in this painting.

As it happens, the University of Toronto itself offers an interesting example of the custom of nude swimming for men. The university’s first student center, Hart House, opened in 1919. Among other facilities, it housed a gym and swimming pool. Because Hart House was open only to men, as stipulated by the principal donor, the indoor swimming pool was monosexual. What’s interesting is that swimming nude was not only permissible, it was obligatory. No swimming trunks were allowed, the official reason being that, because they could shed fibers into the water, they would impede the pool’s filtration system. (Early bathing suits were often made of wool, so the prohibition was not entirely baseless.) This rule remained in force until 1972, when Hart House finally permitted women to use its facilities. From then on, everyone using the pool had to wear a swimming costume.

Of course, Hart House was not exceptional in this era. When the YMCA was an exclusive club for men and boys, bathing suits were optional. Most young men today would probably find this practice astonishing, if not perverse. The mingling of nudity and sex is such that we have trouble imagining that a nude body can be entirely sexless and even uninteresting.

The casualness of nudity in all-male environments is documented in a wide range of sources right up to the postwar era. Anyone who has viewed Dian Hanson’s My Buddy: World War II Laid Bare (Taschen, 2014), based on the Michael Stokes Collection of photographs, will be aware of the degree to which nudity in a male-only context, in this case the U.S. military, was completely acceptable as recently as the 1940s.

From “Innocent” to Sexualized Bodies

That mainstream society’s view of male nudity totally altered during the second half of the 20th century is remarkable, if seldom remarked upon. A revealing example of this revolution may be seen in the changing reception of some of the paintings of the English artist Henry Scott Tuke (1858–1929). Tuke painted a number of scenes with naked youths at their center that we would view as homoerotic but which were deemed “innocent” at the time, because mere nudity (in males) was not seen as intrinsically sexual. Tuke lived in Cornwall for much of his life, painting portraits, sea scenes, and other genres, and sometimes nude young men. Ruby, Gold and Malachite is an example (page 18). Tuke is now generally considered to have been homosexual, and he may well have derived more than artistic satisfaction from painting these adolescent males, but the public viewed his art as perfectly innocent. The City of London purchased Ruby, Gold and Malachite for the Guildhall Art Gallery from the artist himself, following its exhibition in 1902.

For Tuke’s contemporaries—for the heterosexual men who dominated the art world and society in general—male bodies were not viewed as sexual objects, even when naked; only female bodies were. Looking at Ruby, Gold and Malachite today, we wonder how anyone could fail to see its homoerotic (or even pedophilic) undercurrents. Tellingly, the curators of the exhibition Queer British Art 1861-1967, held in 2017 at the Tate Britain museum in London, chose to include this picture as an example of “queer art.” Once innocent, now homoerotic: this painting is a perfect illustration of the degree to which the mainstream perception of male nudity has changed since the early 20th century.

Whatever Henry Scott Tuke’s sexual orientation or artistic inspiration, his many paintings of nude youths in watery environments were uncontroversial in their day precisely because of the entrenched assumption that all men are heterosexual and couldn’t care less about one another’s penises. It was this studied ignorance of homosexuality that allowed artists like Eakins and Tuke to get a pass on images that we would identify as clearly homoerotic today. Only when people started to talk about homosexuality, when its existence was publicly acknowledged, did such representations become controversial or taboo.

That discussion began in the late 19th century, as did much else concerning human sexuality—but only in restricted circles. For most of society, homosexuality remained out of sight and out of mind until the mid- to late-20th century. Thus men who came of age in the 1950s and ’60s, or even as late as the ’70s and ’80s, will remember a world in which it was perfectly normal to strip down in the locker room and shower communally after gym class or a sport. It was the guy who was shy about exposing himself who was seen as peculiar, if not downright girlish. Prudery was purely a feminine trait.

So what happened twenty or thirty years ago that changed all that, causing men to cover up in front of each other, often going to great lengths to avoid the briefest exposure? It was a slow process that’s still going on. What happened, first and foremost, is the gay liberation movement of the 1970s and ‘80s. It enabled our emancipation, but it also blew our cover. Once people became aware of homosexuality, they began to look out for it. Adolescent males in particular began to scrutinize their peers, and themselves, for evidence of gayness. Suddenly there was something else to worry about on that always challenging passage from boyhood to manhood.

This unprecedented awareness of homosexuality, which has been building steadily since the 1970s, is what has changed everything. Just as paintings or sculptures of nude males have become embarrassing or suspect—just watch the nervous response of a heterosexual man to the sight of nude male statuary in a museum—so has male nudity in the real world become problematical, because it is now tainted with the possibility of gay desire. If homosexuality was invisible in the past, now it is everywhere: in the news, at the movies, on TV. And let there be no mistake: it is still a Bad Thing for the vast majority of heterosexual males, who will go to great lengths to avoid any hint of being gay. Hence the uptight locker-room scene that I’ve described. This and other all-male social settings are now heavily policed, or self-policed, for hints of homosexuality.

Of course, there is also a keen awareness on the part of straight gym-goers that there just may be gay men in their midst. And just as they would enjoy checking out nude women if they could, they assume (not incorrectly, perhaps) that the gay guys are checking them out. This concern is compounded by the general tendency to equate nudity with sex, and voilà: young men no longer want to strip naked and shower together. If just being naked with other men is intrinsically sexual, then it is by definition gay.

The effects of this new hyper-awareness of homosexuality extend far beyond the gym. It is as though hetero men have internalized a form of homophobia that’s directed against themselves. Any physical closeness between heterosexual men has become fraught with gay overtones—except in contact sports, where the presence of “virile” aggression and violence erases any hint of homoeroticism. Before the early 20th century, men who were good friends didn’t hesitate to walk arm-in-arm, or with an arm slung around the other’s shoulder. Countless photographs from the 19th and early 20th centuries attest to the warm physicality that could subsist within male friendship. That is almost unheard of now.

I’ve seen young men in my city refuse to sit side-by-side on the bus or subway train; they will leave an empty seat between them or sit on opposite sides of the vehicle, or one will stand. The same occurs at the cinema: male friends trying to leave an empty seat between them—though this trend is said to be waning. I recently overheard one young man tell another that “two men walking under the same umbrella is, you know, kind of gay.”

Heterosexual men are paying an ironic price for gay liberation. It is as though, in order for homosexual and bisexual men to achieve a certain level of tolerance in our society, heterosexual men have had to move away from each other, both physically and psychologically. Any warm feelings that one man may have for another are now a cause for self-doubt and further withdrawal from other men. However, gay men are not to be blamed for this situation. It is only the lingering aversion to homosexuality experienced by many straight men that leads to this insecurity. There are, of course, many straight men who are not homophobic, and they tend to be men who are perfectly confident in their sexuality. Perhaps this is something that comes with age, which is why many men do seem to become more relaxed in the locker room as they get older.

Nevertheless, I think we have a right to be a little depressed about the new prudery. Things are better for gay people since the start of gay liberation, to be sure, but homophobia has not died out, contrary to our earnest hope. Instead, it has transmogrified into something else, an unexpected consequence of the LGBT movement itself and the widespread awareness of gay people (as in the slogan “We are everywhere!”). Straight men pay a price for their fear of exposing themselves, both literally and metaphorically, to other men. But to the extent that their fear of intimacy reflects an awareness of gay men’s presence, it is a constant reminder to be on our guard.

Now retired, Steven Spencer worked for 26 years as an interpretive planner at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada.