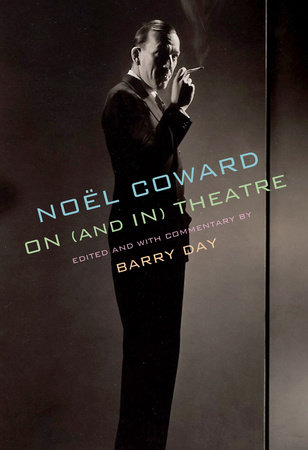

NOËL COWARD ON (AND IN) THEATRE

NOËL COWARD ON (AND IN) THEATRE

Edited by Barry Day

Knopf. 496 pages, $40.

IT’S HARD TO IMAGINE, in the age of Disney+, Amazon Prime, Netflix, Hulu, and HBO, that when the playwright Noël Coward (1899–1973) was growing up, the London stage was the center of the English-speaking world of entertainment—and such a pot of gold for writers that it even tempted Henry James to write plays. James was never able to figure out the art form that made playwrights like J. M. Barrie (Peter Pan) and Oscar Wilde rich and famous. He was, to his horror, booed during curtain calls at the premiere of his play Guy Domville—in the same theater that would host, not long thereafter, and to great applause, The Importance of Being Earnest.

But in Barry Day’s splendid compendium of interviews, letters, speeches, and table talk by Noël Coward (along with 138 illustrations), we travel back to a world in which Coward was the epitome of style, glamour, and theatrical success, particularly between the two world wars—a Renaissance man who wrote songs and plays, acted, and directed in a career that stretched from the heyday of George Bernard Shaw to that of the Angry Young Men like John Osborne (Look Back in Anger). Coward went from singing in church to performing in Las Vegas after his plays were no longer hits. What makes this book so interesting is the historical sweep—the fact that Coward’s mentors were George Bernard Shaw (who had to tell Coward to stop imitating his work and be himself) and Somerset Maugham (who, unlike Henry James, got rich writing plays for the London stage), whereas in his later years he was appraising the work of Harold Pinter and Edward Albee. Nothing is more interesting in Day’s book than the chapter in which Coward assesses the work of other playwrights, like Barrie, Maugham, T. S. Eliot, Eugene Ionesco, Samuel Beckett, and finally Osborne, Terrence Rattigan, Albee, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, Eugene O’Neill, and Peter Shaffer.

Writing, Coward believed, was superior to acting because writing lasts and performances happen only once. And that single occasion was not always magical: “I have been having a terrible time with After the Ball,” he wrote about one of his plays, “mainly on account of Mary Ellis’s singing voice which, to coin a phrase, sounds like someone fucking the cat.” Alas: “She couldn’t get a laugh if she were to pull a kipper from her twat.”

Coward wrote dozens of plays, but the four comedies for which he’s best remembered are probably Hay Fever (1924), Private Lives (1930), Design for Living (1933), and Blithe Spirit (1941). He began performing as a choir boy, “but I hated doing this because the lack of applause depressed me.” Years after being cast at the age of ten in a children’s play called The Goldfish, he admitted: “I was a brazen, odious little prodigy, over-pleased with myself and precocious to a degree. … I was, I believe, one of the worst boy actors ever inflicted on the paying public.”

By the time he was in his twenties, however, he’d learned a lot, though most of his early plays were forgettable at best, until The Vortex (1924), a play about a young man addicted to drugs and a mother addicted to serial love affairs. The Vortex shocked the critics and made him a star. “Success,” he said, “took me to her bosom like a maternal boa constrictor.”

After that, he was for many years the public face of a particular style of sophistication, one associated with the Bright Young Things: English aristocrats (though Coward’s parents were working-class poor) who spent their time getting divorced, saying brittle modern things to one another, and smoking cigarettes—lots of cigarettes. In fact, in the many photos of him in the book, Coward is almost always holding one. In one iconic photograph, Gertrude Lawrence, his costar in Private Lives, has hers in a very long cigarette holder. It was all about the cigarette—the angle at which it was held.

After that, he was for many years the public face of a particular style of sophistication, one associated with the Bright Young Things: English aristocrats (though Coward’s parents were working-class poor) who spent their time getting divorced, saying brittle modern things to one another, and smoking cigarettes—lots of cigarettes. In fact, in the many photos of him in the book, Coward is almost always holding one. In one iconic photograph, Gertrude Lawrence, his costar in Private Lives, has hers in a very long cigarette holder. It was all about the cigarette—the angle at which it was held.

Although Coward felt that when one was a star, one should behave like one, he had a down-to-earth view of this role. He was first and foremost a writer: “It seems to me that a professional writer should be animated by no other motive than the desire to write and, by doing so, to earn a living.” He was just as critical of his own work as he was of others’. About his play Conversation Piece in 1934: “The play itself, I think, is dull and garbled and I am faintly ashamed of it.” After all, “writing is work.” But “the only way to enjoy life is to work. Work is much more fun than fun.”

Noël Coward on (and in) Theatre is composed rather like a scrapbook, with photographs, reproductions of Playbills and theatrical posters, excerpts from Coward’s essays on the theater, interviews he gave, his plays, his bon mots, his opinions of fellow playwrights, actors, producers, and critics, and even poems and song lyrics. The book is divided into six chapters, with an “Intermission” on “Star Quality” (“I don’t know what it is, but I’ve got it!”). Three of them deal with how he wrote his plays, the rest with everything else. Finally, “Curtain Calls” ends with an essay he wrote called “The Decline of the West End.” We also get subsections of these chapters devoted to: “Coward on Talent or the Lack of it”; “Coward on Timing”; “Coward on Clarity of Delivery”; “Coward on Stage Fright”; “Coward on Being ‘Noël Coward’”; “Coward on Not Being ‘Noël Coward’”; “Coward on Vice and Squalor in the Theatre.”

Coward’s view of his milieu was simple: “The primary purpose of the theater is to amuse, not to reform, improve, or edify people.” (I guess times have changed.) “I’ve decided I’m not an O’Neill fan. … The Iceman Cometh—and I wenteth. … Long Day’s Journey into Night turned into Day’s short journey to the Exit at the first intermission.” After seeing a production of Chekhov’s The Seagull: “I hate plays that have a stuffed bird sitting on the bookcase screaming—‘I’m the title! I’m the title!’” He had no illusions about his own aspirations. “I could no more sit down and say—‘Now I’ll write an Immortal Drama’ than I could fly, and anyway I don’t want to. I have no great or beautiful thoughts.” What he did have was what one of his biographers would call A Talent to Amuse. Of course, the English theater has always valued that. Even the plays of George Bernard Shaw, which seem cerebral to us now, floated on streams of witty repartee. And then there was the author of A Woman of No Importance and Lady Windermere’s Fan.

The biggest surprise in Day’s book is probably Coward’s feelings about Oscar Wilde: “All my life I’ve been accused of being like Wilde or Congreve, but the truth is—I’m not a bit like either.” A director of one of Coward’s plays explained it this way: “Everything that Noël sent up, Wilde was sentimental about, and everything Wilde sent up, Noël was sentimental about. … It was like having two funny people at a dinner party.” Still, it’s odd to come upon this reaction to The Importance of Being Earnest in Coward’s diary: “It is xtraordinary indeed that such a posing, artificial old queen should have written one of the greatest comedies in the English language.” He was contemptuous even after reading De Profundis: “Poor Oscar Wilde, what a silly, conceited, inadequate creature he was and what a dreadful self-deceiver. It is odd that such a brilliant wit should be allied to no humour at all. … The trouble with him was that he was a ‘beauty-lover.’”

The last line is startling. And so is Coward’s estimate of Somerset Maugham when his mentor grew old. By the time he was senile, Coward was calling him a “Disagreeable old sod!” and “that scaly old crocodile. … The Lizard of Oz.” The reason? “Maugham hated people more easily than he loved them. I love people more easily than I hate them. That is the difference between me and Somerset Maugham.”

The author of Hay Fever could not understand the gloom that seemed to take over young playwrights after World War II. In 1948, he had dinner in New York with Tennessee Williams and Gore Vidal: “Vidal intelligent and charming, Tennessee less charming but curious. They both gave out a sort of ‘end of the world’ feeling; they were good company but doomed. I felt sorry for them.” Later, having seen one of Williams’ hits, he wrote in his diary: “Went to Tennessee’s new play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof—full of adolescent sex, dirty words and frustrations, but at moments very fine. It was beautifully played but over-directed by Elia Kazan.” Of Sweet Bird of Youth in 1959: “Like all of Tennessee’s plays it has moments of brilliant writing but the play is not really good. None of the characters is really valid and the emphasis on squalor—drugs, syphilis, castration, sex, sex, sex—is too heavy and almost old-fashioned.” (Ironic, to say the least, coming from the author of The Vortex.)

There was something about Coward—perhaps that he stood for Theater—that drew young playwrights to him. Included in Day’s book is a photo of a handsome young Edward Albee (“very intelligent, but badly tainted with avant garde, Beckett, etc.”) with Coward’s arm around his shoulder. As time goes by, he sounds more and more like an old fogey, but really he was simply sticking to his fundamental principle: that the theater should amuse—no one wants to hear about your private troubles. On Albee’s Tiny Alice: “Altogether maddening evening in the theatre, so nearly good and yet so bloody pretentious. I told Edward what I felt, and he was very amiable about it.” There’s lots of tips for writers in this book. One of the most valuable may be the discovery that the plays he worked hardest and longest on were mostly flops; the ones he wrote in five or ten days are the ones we remember.

Exactly how Coward was “read” when he was an international star is not elaborated in this book, but the question piques one’s curiosity. The song “Mad About the Boy,” for instance, is the monolog of a young woman who’s fallen for a lad on the silver screen, and yet, if you go to YouTube, you can find not only an album cover with a young Coward beside the title, but Coward himself singing the song, something that makes the lyrics much more poignant, as many comments attest. Here’s the first stanza: “Mad about the boy/ I know it’s stupid to be mad about the boy/ I’m so ashamed of it/ But must admit the sleepless nights I’ve had/ About the boy.” Was it just assumed by the public that Coward was singing it simply because it was his own song, or did they realize he was homosexual and not care, or did only his fellow poofters know the reality? Day does not go into this. Whatever the answer, he was one of those people—as Vito Russo showed in The Celluloid Closet—who made no attempt to butch it up and were accepted anyway, indeed enjoyed because of it.

From Ivor Novello to Laurence Olivier, from Gertrude Lawrence to Mary Martin and Elaine Stritch, Coward’s career spans so many changes not only in theater but in the culture itself that Barry Day’s scrapbook is a treasure trove for theater mavens, fans of Coward, and students of social history. In an era when people get on airplanes in shorts and flip-flops and watch movies on their smartphones, one may well ask: What does Coward have to say to us? His world has vanished along with the British Empire, the Bright Young Things, cigarette holders, and the shock value of divorce. Even the songs Coward composed (classics like “I’ve Been to a Marvelous Party,” “Mad About the Boy,” “Someday I’ll Find You”) came from an English music hall tradition that has disappeared. What lasts are the plays. Who knew there were so many? As for the sophisticated patter, the belief that whatever else it does, the theater should entertain, Day’s book reminds us that all of that was based on hard work and discipline. Coward was, for a man associated with insouciance, utterly dedicated.

“Work hard,” was his advice, “do the best you can, don’t ever lose faith in yourself, and take no notice of what other people say about you.” Still, it should come as no surprise, I suppose, that playing in London at the Noël Coward Theatre on the day I write these words is the musical Dear Evan Hansen—an American import.

Andrew Holleran is the author of the novels Dancer from the Dance, Nights in Aruba, The Beauty of Men, and Grief.