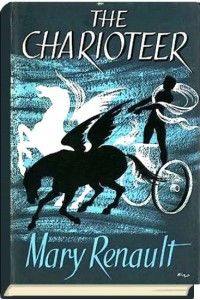

BEST KNOWN for her historical novels set in ancient Greece, many with overtly homosexual themes and scenes, Mary Renault began her career with a novel set in modern times called The Charioteer (1953). Taking place during World War II, the novel  recounts the story of a wounded soldier named Laurie “Spud” Odell who is both torn between two lovers and conflicted about his own homosexual feelings. One of his lovers is similarly confused, but the other, a naval officer who’s a veteran of the British public school system, seems quite comfortable with his sexual leanings and accepts himself as a different kind of man.

recounts the story of a wounded soldier named Laurie “Spud” Odell who is both torn between two lovers and conflicted about his own homosexual feelings. One of his lovers is similarly confused, but the other, a naval officer who’s a veteran of the British public school system, seems quite comfortable with his sexual leanings and accepts himself as a different kind of man.

That The Charioteer was read as a “gay novel” is demonstrated by the fact that it became an instant bestseller among homosexual readers soon after its publication. Indeed if there’s a case to be made for it as “the first” such novel, it lies in the fact that it found a large and eager audience of gay readers—as did Renault’s next novel, The Last of the Wine (1956). Indeed these two novels undoubtedly provided much of the American reading public with its first exposure to homosexual themes and characters. And while The City and the Pillar (1948) had sold quite well a few years earlier, author Gore Vidal had seen fit to create two angst-ridden protagonists one of whom murders the other in the final scene. Renault, in contrast, took pains to portray same-sex relations in a positive light, notably in The Mask of Apollo (1966) and in The Persian Boy (1972), which effectively outed Alexander the Great.

Taken together, these books might qualify Mary Renault, herself a lesbian, as the first gay novelist, as she wrote not a one-off novel about same-sex love but a body of work that kept it front-and-center as a recurring theme.

Following is an essay by the late Alan Conrath, slightly edited by me, which appeared in the May-June 2004 issue. — RS

Alan Brady Conrath, who died in 2005, was a writer and poet—by day an accountant—based in Boston.