FASHIONING MASCULINITIES

The Art of Menswear Victoria & Albert Museum

March 19 to November 6, 2022

FASHIONING MASCULINITIES

FASHIONING MASCULINITIES

The Art of Menswear

Edited by Rosalind McKever and Claire Wilcox

V&A Publishing. 272 pages, $60.

VIRGINIA WOOLF, author of the gender-bending mythical biography Orlando, would have delighted in Fashioning Masculinities: The Art of Menswear, a comprehensive exhibition at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum—and its accompanying catalog—which deliberates upon the sartorial representations of masculinity through the ages. On the topic of fashion Orlando remarks: “Vain trifles as they seem, clothes have, they say, more important offices than merely to keep us warm. They change our view of the world and the world’s view of us.” Rosalind McKever and Claire Wilcox, the exhibition curators and book editors, survey paradigms of masculine fashion and maintain the centrality of clothing as a signifier of class, culture, gender, political ideology, and race.

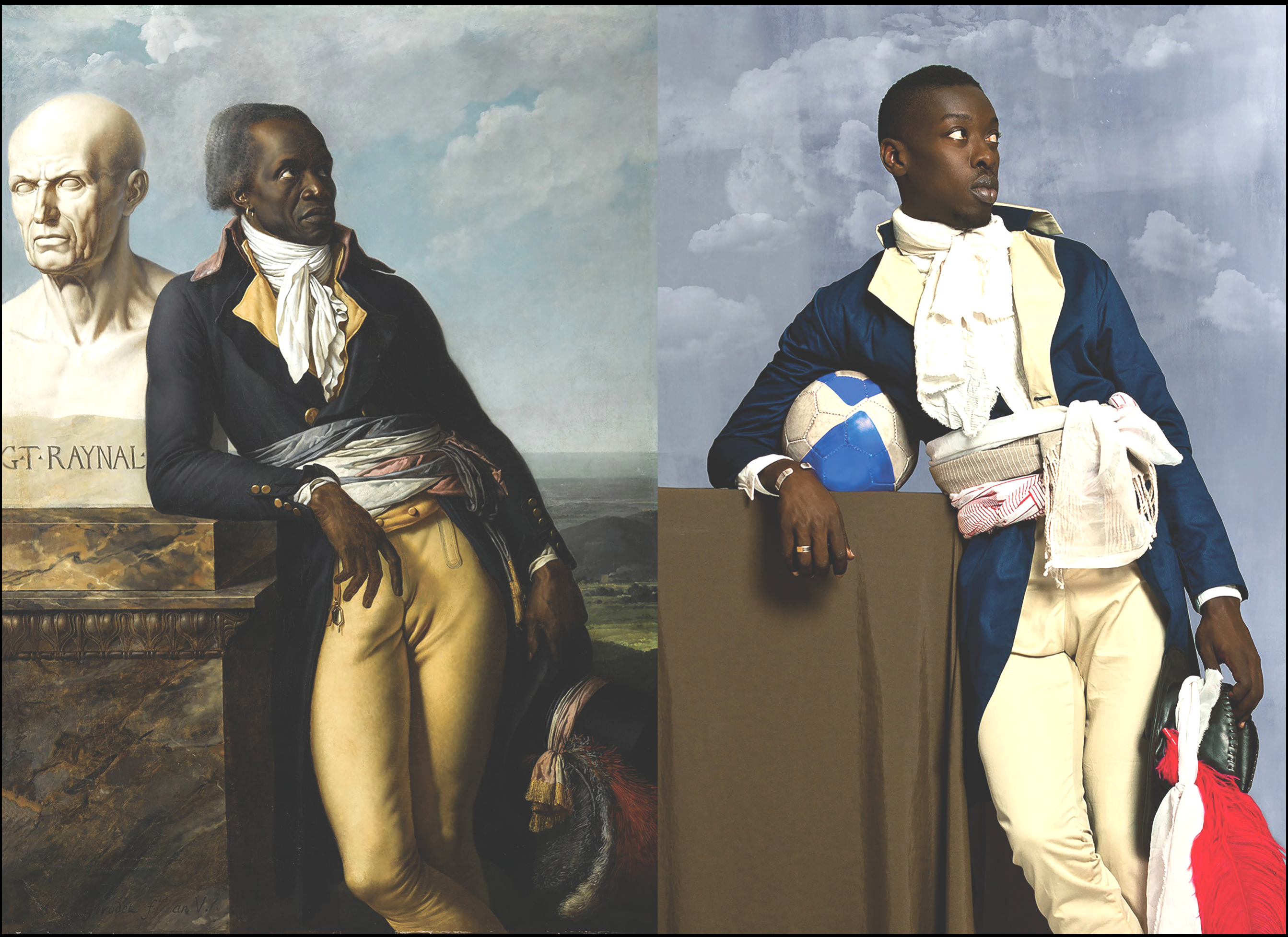

The image selection for the cover of the catalog, a recent self-portrait by Senegalese photographer Omar Victor Diop, captures some of the exhibit’s themes. The photograph is a re-imagining of a late 18th-century painting by the French romanticist Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, of a portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley, a formerly enslaved person from Saint-Domingue who gained his freedom and fought in both the American War of Independence and the Haitian Revolution. Diop juxtaposes the contemporary with the historical using costume, props, and poses, such as depicting Belley in a parliamentary uniform with a modern football under his arm, which is a reference to the racist mistreatment of African footballers by Europeans (Figure 1). The exhibit also uses performance videos such as Matthew Bourne’s New Adventures, a rendering of Pas de Quatre, a 19th-century traditional ballet with all-male dancers costumed in men’s underwear. Changing cultural contexts are explored in two paintings that hit the viewer with competing flares of pink-puffery and moiré satin extravagance, first in a painting by Joshua Reynolds titled Portrait of Charles Coote, 1st Earl of Bellamont (1738-1800), next in a face-to-face encounter with designer Harris Reed’s portrait Fluid Romanticism (Figure 2).

Divided into three main galleries, “Undressed,” “Overdressed,” and “Redressed,” the exhibition spans the centuries with wide-ranging displays from classical sculptures, Renaissance paintings, and 17th-century military body armor, to 20th-century underwear, T-shirts and jock straps, and a 21st-century velvet tuxedo gown by designer Christian Siriano worn by Billy Porter on the red carpet of the Academy Awards in 2019.

Fig. 2. Left: Joshua Reynolds. Portrait of Charles Coote, 1st Earl of Bellamont, 1773-74. Middle: Photo by Giovanni Corabi. Harris Reed, Fluid Romanticism. Left: Harris Reed on Harper’s Bazaar, April 2022.

§

Queer æsthetics have had a singular influence on the sensibilities of modern fashion. Many if not most of the iconic fashion designers from the 20th century golden age of style were gay men: Christian Dior, Perry Ellis, Halston, Yves Saint Laurent, Willi Smith, Valentino, Gianni Versace, Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana, Jean Paul Gaultier, Tom Ford, Marc Jacobs, Michael Kors, Karl Lagerfeld, Alexander McQueen, et al. In tandem with the innovations of fashion designers were queer photographers, who have been instrumental in shaping fashion and in creating fashion houses. The Hollywood film portraitists Cecil Beaton and George Hurrell inspired fashion photography, an avant-garde of fashion photographers led by Baron de Meyer, Horst B. Horst, George Hoyningen-Huene, George Platt Lynes, Steven Meisel, Herb Ritts, Francisco Scavullo, and Bruce Weber. George Platt Lynes’ photograph Nude Boy (1937) is included in the exhibit because of Lynes’ profound impact upon fashion iconography. Historian Elspeth H. Brown in her book Work!: A Queer History of Modeling asserts that Lynes’ so-called “amorous regard” or “amorous glance” became the fashion model’s look—the exchange of glances central to queer desire: “[T]he fashion tableau references public outdoor cruising practices.”

During the euphoric 1970s, Peter Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe were immersed in New York’s downtown art and homosexual underground, and their photography bears witness to it. They cruised the pre-gentrified districts of Greenwich Village before displacement—on the Hudson River waterfront piers, at the graveyard shift in the Meatpacking District, and in the after-hours sex clubs. Their work may be considered marginal to fashion. Still, sartorial tropes appear in many of their images, often campy, parodic, and cynically subversive. Both Hujar and Mapplethorpe understood the importance of fashion in constructing subcultures and identities. Queer cultural historian Jack Fritscher wrote in Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera: “Robert was a canny fashion photographer, creating fashion by cruising the streets and bars where, as Vivienne Westwood knew, fashion happens first. From the leather bars and the movies, Robert texturized leather peerlessly in his photographs of chaps, vests, gloves, jackets, and hoods.” Included in the exhibit is Mapplethorpe’s portrait of former bodybuilder Arnold Schwarzenegger (1976), which points to the photographer’s interest in Classicism and an attitude toward the self, the body, and personal identity. In a couple of images of Ken Moody, his most photographed subject, he satirizes high fashion with the model portentously about to devour a stiletto shoe or balancing one on his butt. He was transgressive about gender, going into territory beyond his leathermen images, as in Self-Portrait (1980), where he’s in partial drag with makeup, his hair coiffed into voluminous curls, and wearing a fox fur boa.

Peter Hujar’s encounter with fashion dates to 1967 when he attended a master class taught by photographer Richard Avedon and art director Marvin Israel. He would later shoot for Harper’s Bazaar and GQ. He made portraits of performers in the backstage dressing rooms of theaters and nightclubs. Many performance artists posed for him, including members of the Cockettes, Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo, and the Theatre of the Ridiculous, including Ethyl Eichelberger, John Edward Heys, Charles Ludlam, Larry Ree, and Mario Montez. Several of his best-known images were Warhol superstars, such as Candy Darling on her Deathbed (1973) and Jackie Curtis Dead (1985), employing dramatic chiaroscuro lighting techniques. The photograph Christopher Street Pier #2 (Crossed Legs) (1976) uses only a few items of clothing—well-worn work boots and athletic socks—as signifiers. The location is a pier on the Hudson River. Hujar was a consummate storyteller, and this is an example of his photographic narrative technique. In this image, we see only the legs of a reclining man, his face blocked by his crossed legs in a campy pose reminiscent of a high-kick dancer. The gay clone uniform requires only few items of clothing to identify the subject as a gay man. While he appears to be sunbathing, it’s more likely that he’s cruising in a well-traveled Greenwich Village gathering place.

§

While it may seem that the promotion of cosmetics, skincare, and beauty products for men is a recent phenomenon, masculine grooming has its roots in the 18th century with the proliferation of elaborate male grooming paraphernalia. The exhibit includes a veneered satinwood and leather, velvet-lined dressing-case, tortoiseshell shaving sets, and silver tweezers. Alan Withey’s catalog essay “A Polished Impression” explains that, as part of an interest in physiognomy in the 18th century, eyebrows were considered an indicator of character, and men plucked and dyed them accordingly: “the ideal shape eyebrows was arched; thick, bushy eyebrows were viewed as a potential sign of clownishness; while those pointing downwards suggested malice.” The exhibit follows masculine grooming into the 20th century with the photograph Ted with Comb (1977) by Chris Steele-Perkins. It’s a portrait of a Teddy Boy, a member of a teenage, working-class subculture in Britain in the 1950s and ’60s. They wore flamboyant Edwardian-style clothing—long drape jackets with velvet collars, tight drainpipe trousers, bootlace ties, and thick crepe-soled shoes. Teddy Boys had heavily greased hairstyles molded with Brylcreem into a glossy ducktail. Ideas of masculinity are reflected in male hair grooming. Photographs of Elvis Presley obsessively combing his coal-black hair into a pompadour in front of a mirror were legendary. In 1958, when he was inducted into the Army, his closely cropped G.I. haircut stunned his fans worldwide, becoming a historic pop culture event. Mapplethorpe embraces the ducktail as a symbol of countercultural nonconformity in Self-Portrait (1981), wearing a motorcycle jacket with only the back of his head visible with a slicked-back punkish hairstyle.

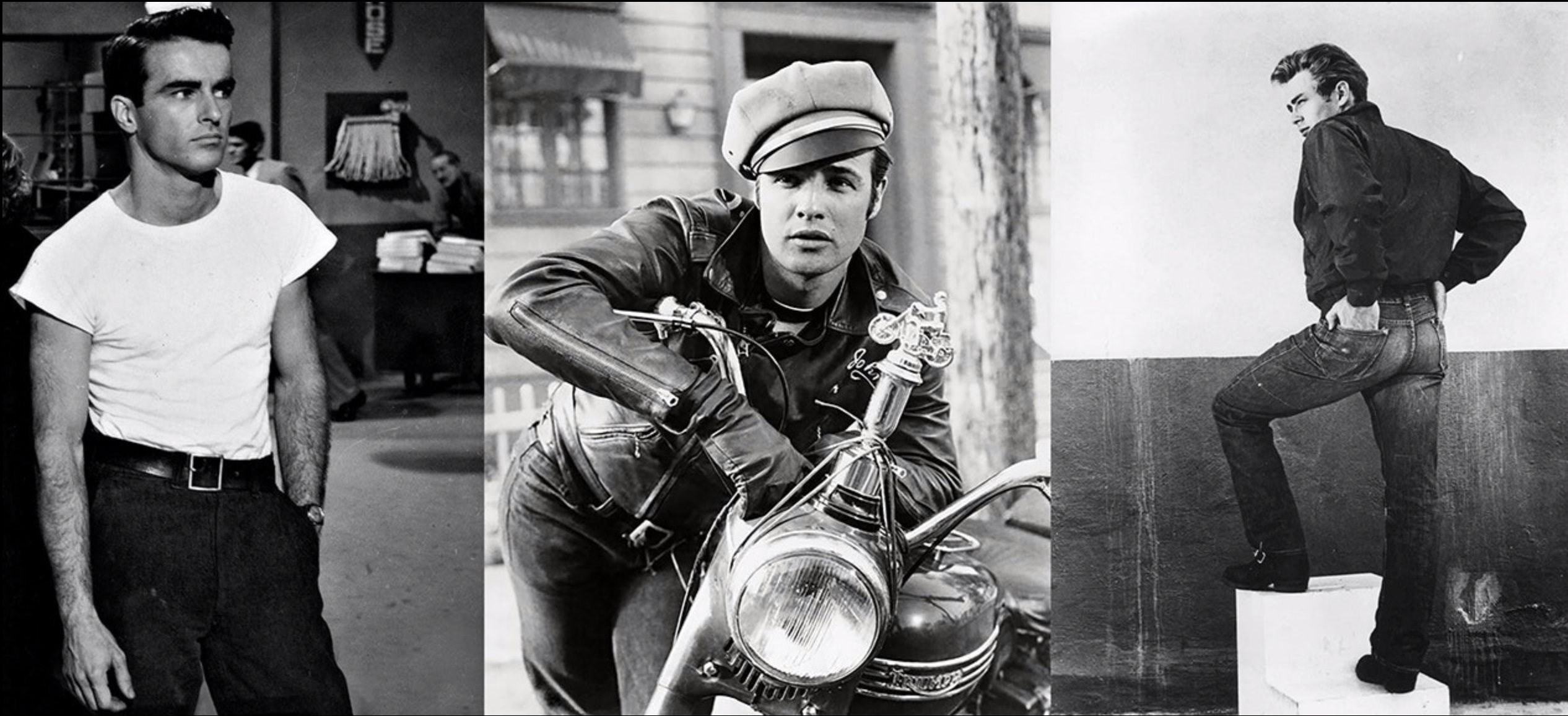

Male grooming behaviors can be seen as ritualized performances, and they pop up in several noteworthy films. In Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963), Bruce Byron, playing the lead character of Scorpio, while preparing for a night out becomes metamorphosed into an archetypal leatherman as the camera wanders into adjoining areas of the bedroom in a fetishistic montage of sartorial accouterments—a motorcycle jacket, chains, and belts. The walls are decorated with photographs of icons like James Dean and Marlon Brando, whose portrayal of Johnny Strabler in The Wild One (1953) was influential in shaping homosexual identity through costume, particularly the asymmetrical motorcycle jacket, symbolizing—for some viewers at least—the rebelliousness that inspired the biker and gay male leather subculture of the era. That sensibility can be seen in the hypermasculine figures in the art of Tom of Finland and Rob of Amsterdam, which displays the sartorial bravado of biker jackets, chains, engineer boots, garrison belts, harnesses, key rings, neoprene wristbands, and police and highway patrol uniforms.

Of Brando’s appearance in a torn, sweaty T-shirt in the Broadway production of A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), Gore Vidal later remarked: “There was an earthquake.” It signaled the postwar trajectory of the T-shirt (previously an undergarment) and the rise of street style, the semiotics of a “cool” and detached masculinity. Montgomery Clift wore a T-shirt and leather jacket in A Place in the Sun (1951), his hip-slanted swagger hinting at homoerotic availability.

The exhibit includes a publicity photo of James Dean from Rebel Without a Cause (1955) in which he’s looking over his shoulder as seen from behind, wearing very tight jeans that accentuate his backside, as does his hand in a back pocket. The only missing element is the hankie code bandana. This image epitomizes Dean’s homoerotic appeal (Figure 3). In On the Road (1957), Jack Kerouac wrote of “his muscular neck, T-shirted in the winter night.” He understood the symbolism of the T-shirt. The exhibit displays Bruce Weber’s well-known, controversial photograph known as “Advertising campaign for Calvin Klein underwear, 1982, Model: Tom Hintnaus.” On the Greek island of Santorini, the suntanned Hintnaus was photographed like a bronze statue against the wall of a whitewashed cubiform house wearing crisp, blindingly white briefs. When a monumentally large ad was used on a billboard above Times Square displaying Hintnaus’ conspicuous bulge, rubbernecking motorists literally stopped traffic.

A photograph of a jockstrap designated “Duribilknit, Jockstrap. Wool and surgical elastic. New York, c. 1947” appears in the exhibition catalog. The jockstrap is a symbol of dynamic, athletic masculinity, and from its development in the mid-20th century, it has emphasized male virility for those wanting to look bigger, using seams around a pouch and an additional inside pocket in some cases.

The erotic function of supportive garments for men dates back centuries. Long before jockstraps there were codpieces, such as the highly decorated ones from the 15th century that were worn to draw attention to men’s junk. In the essay “Hard and Straight: The Creation of Nineteenth-Century Masculinity Through Corsetry” in Crossing Boundaries: Fashion to Deconstruct and Reimagine Gender, historian Alanna McKnight wrote: “Codpieces were noteworthy not as sexual invitations to women but as symbols for social, temporal, and territorial power.” Darth Vader and the Storm Troopers wore codpieces as genital armor in Star Wars (1977), and Tom Cruise wore one in the film Rock of Ages (2012). In the leather subculture, a re-envisioned codpiece appeared that was part cockring and part genital armor. When director William Friedkin was scouting locations for the film Cruising (1979), he went to the Mineshaft—the notorious New York sex bar—on jockstrap night and later reported: “Everyone was in a jockstrap, some with leather boots and vests, executioner masks, or leather jackets. Men of all races, colors, and social status mingled as equals.”

After Andy Warhol was shot by Valerie Solanas in 1968, he had numerous surgeries and was deeply scarred. He wore corsets to support his internal organs. Always the artist, many of the corsets were hand-dyed solid colors—blue, green, yellow, and pink. Historian Alanna McKnight says in her essay “Hard and Straight” in Crossing Boundaries: “Corsets are garments that are now seen as quintessentially feminine; however, through the nineteenth century men also wore corsets to not only form their bodies but also to form a masculine ideal.” They were worn by men in the 19th century to structure their bodies into paradigmatic masculinity. Corsets and harnesses have emerged along with male décolleté and exposed butt cleavage at public events: Timothée Chalamet in a rosette-embellished harness at the Golden Globes 2019; Michael B. Jordan in an embroidered bib at the SAG Awards 2019; Lenny Kravitz in a lace-ruffled bodice with a sheer corset at the Met Gala 2022, where Evan Mock showed up in corset-detailed suit and Ben Platt in corseted suit with black pumps.

In 2020, Harry Styles made media history as the first man to appear on the cover of American Vogue. He wore a Gucci lace-trimmed ball gown and tailored tuxedo jacket. A new generation of queer artists is challenging homophobia and misogyny in film, television, and music, including hip-hop and rap (Figure 4). Most prominent is openly queer Lil Nas X, who wore an ensemble designed by Donatella Versace at the Met Gala 2021, which consisted of a dramatic cape, gold-plated armor, and a crystal-beaded bodysuit. Nas is well aware of the homoerotic possibilities in the song “Jailhouse Rock,” which includes the lyrics “You’re the cutest jailbird I ever did see./ I sure would be delighted with your company./ Come on and do the Jailhouse Rock with me.” Elvis performed the song in the film of the same name with gyrating pole dancing; and Freddy Mercury performed it strutting shirtless and sweaty. Nas’ prison-themed version in his music video “Industry Baby” is overtly sexual, with inmates dancing naked in a communal shower.

Since the late 20th century, representations of gender have been challenged by feminists and transgender and LGBT activists in resistance to hegemonic, immutable constructions. The reformulation of gender has dominated academic, social, and political discourse with genderqueer people in the vanguard. The world of fashion, too, can be subversive and transgressive.