OF ALL the childhood aphorisms jostling within my grown-up mind, the one about judging books by their covers surged to the surface when I first saw Michael Kearns’ new book, The Truth is Bad Enough: What Became of the Happy Hustler? (CreateSpace, 2012). Next to the subtitle there appears an alluring photograph of the young Kearns cradling a teddy bear. The back jacket is peppered with celebrity and literally oozes Hollywood Fabulous, making this precisely—to be honest—the kind of book I used to sigh over and reshelve within the ever-diminishing queer section at the late Borders Books. “Hollywood’s first openly gay actor … puts most other show-biz autobiographies to shame,” boasts Sir Ian McKellen. Impressive, yes. But please! The “who’s on first” game is best saved for baseball or sketch comedy. Such “glamorism” isn’t activism, is it?

Knowing Kearns, I knew to think twice. I first met him in 1999 as a colleague working to open USC’s ONE Institute & Archives. I interviewed him formally in the summer of 2005 as part of my research on the history of GLBT activism in Los Angeles. My second interview with Kearns, occasioned for this article, arose from a heightened interest in branding and labels inspired by my impressions of the cover of his new book.

Kearns notes in the book that the words “actor” and “activist” both stem from the word “act”: to exert energy or force. This connection, though, took him decades to perceive, and for a long while the tension between being and actor and becoming an activist “played havoc” with his sense of identity. Kearns first became known to the American public as “Grant Tracy Saxton,” author of the autobiographical book, The Happy Hustler (1975). The gregarious central character was largely a construct of Kearns’ first lover, Thom Racina. Following on the success of Xaviera Hollander’s The Happy Hooker (1972), Racina wrote Hustler and then hired the handsome Kearns to be the “true” author of the book.

Kearns filled the Saxton role admirably. His lean, farm-boy torso graced the cover of The Advocate in November 1974, and he was featured on the talk-show circuit for a whole year after Hustler’s 1975 publication, including guest appearances on Donahue and the late-night show Tomorrow with Tom Snyder. The book met with far greater success than he or Racina had anticipated, but the pressure of living the lie exacted considerable penalties over time. In fact, it almost killed him.

Kearns filled the Saxton role admirably. His lean, farm-boy torso graced the cover of The Advocate in November 1974, and he was featured on the talk-show circuit for a whole year after Hustler’s 1975 publication, including guest appearances on Donahue and the late-night show Tomorrow with Tom Snyder. The book met with far greater success than he or Racina had anticipated, but the pressure of living the lie exacted considerable penalties over time. In fact, it almost killed him.

This conflict between “acting” and “being” drives much Kearns’ early life—and provides the compelling impetus for The Truth Is Bad Enough. Another agonizing force in Kearns’ life, however, repeatedly emerges from society’s demand that he compartmentalize himself into particular and discrete categories. As I reflected over our second interview, I realized to what degree I had been complicit in this. Curious about the transition from actor to activist he portrayed in the book’s second of three “acts,” my first question was: At what point does something you do become something you are? How does one know when a threshold has been crossed?

“I’ve never crossed any thresholds or opened any closets,” came his reply. “Being gay and being an actor are inextricable. I don’t compartmentalize myself.” Unfazed and a bit perplexed, I pressed on. Reflecting on how his sense of self and purpose had changed dramatically in the book due to the arduous process of adopting his daughter, Tia, I asked: “Did becoming a father make you feel somehow less gay?” His response: “Becoming a father made me feel more gay. More human. More female. More male.”

The first two “acts” of the book concern Kearns’ battle with alcoholism, sex addiction, and HIV, so I next asked if he perceived sex addiction to be a personal affliction best left for psychologists, or if it should be treated more as a social disease that could perhaps be tackled by social scientists like myself. Again Kearns resisted my attempt to pin his wings to the velvet. “We’re all complicated,” he said: “There’s a fine line between sexual freedom and sexual addiction. I don’t want to be the one to define either, except for myself. My depression was clearly realized in conjunction with having a lot of sex and feeling increasingly empty. I’m not sure that sexual addiction per se is a ‘social disease.’ But it can be teamed with a plethora of social diseases. It’s really something someone has to self-diagnose—and then do something about. It doesn’t mean stop having sex. Or even stop having lots of sex. But what’s the motivator of the sex? I was trying to feel loved, wanted, younger—not good when you’re in your fifties. When I stopped pigging out on so much sex, I did feel loved, wanted, and younger—in many different ways.”

For Kearns, actor merged with activist in the early 1980s, when death galvanized him into manhood. In response to the growing AIDS crisis, Kearns and his partner, James Carroll Pickett, cofounded Artists Confronting AIDS in Los Angeles. They wrote and produced AIDS/US in 1986, a docudrama portraying early victims and first responders to the plague. Spectators and performers alike were “transfixed by the authenticity of the work,” states Kearns in his book. The experience, he told me, was a spiritual confluence in which “theater and church combined.”

Through the melancholy second act of The Truth Is Bad Enough, dozens of friends and his first two lovers wither in Kearns’ arms. He watches them die wondering if they had lived a life of purpose. Would they be remembered? AIDS/US was Kearns’ reply to them in the affirmative. Night after night, a damp-eyed audience came to empathize with the lives re-enacted onstage. He asked in our first interview: “Is it tragic that many of us achieve our political zenith as a result of 45 of our friends dying? It is sad. But it did make us into something. It gave us some kind of fiber—some kind of strength and metal.” Now, he added: “The multiple deaths took me to a deeper place as a person and an artist. In fact, I don’t believe I really looked at myself as an artist before I started dealing with AIDS’ devastation.” Through the success of AIDS/US, Kearns was reminded that where performance meets persuasion, things get political real fast.

Morris Kight, the late doyen of Christopher Street West, L.A.’s gay pride organizer, first recruited Kearns into activism soon after The Happy Hustler’s publication, and the two remained close friends. Kight, a formidable publicist and political strategist, taught Kearns that one’s life could be plotted much like a play. The key was patience, learning when to restrain and when to let go—a skill cultivated in the theater. Under Kight’s ægis, Kearns waited until the right moment to come out as HIV-positive: a 1992 interview on Entertainment Tonight in which the first openly gay actor in Hollywood became the first openly gay actor with HIV.

From here on, his identity as an activist was honed, and that role took on a renewed importance. After four decades of HIV activism, Kearns has garnered dozens of awards for his work both on and off stage. Yet he considers his most important work as an activist to have been fostering and ultimately adopting his daughter, Tia. On a personal level, the adoption signified a turning point in his life when he began to plan as if he had decades of life ahead of him, not just a few weeks. As an activist, though, fatherhood gave him credibility. All of the former theatrics and grandstanding—despite the validity of his message—now felt more legitimized, more real: “I think that my living with Tia as a black child—of course this is about class and about gender and race, it’s about all kinds of different social issues that I’d been preaching—this was the single manifestation of my political mandate. Because it is very human. And you couldn’t be more human. But if you want to look at it from a political point of view, and then you ask me what did I most accomplish, that’s it! There is no question.” Accordingly, some of the most pleasant compliments Kearns receives come from those who come to know his story and likewise decide to adopt.

Kearns concludes that many of his life’s conflicts had been self-imposed, derived from the process of reconciling the man to the boy who had fathered him and embracing core aspects of his personality that he had confronted in childhood and then rejected through prolonged adolescence. Consequently, the third and final “act” of Truth, where he becomes a father, is a return to the passions and values that had motivated him in youth. “In so many ways, I am, as a nearly 63-year-old man, the same little boy I was as far back as I can remember. I love sexiness, I love men, I love to perform, I love drama, I love to tell stories, I love to help people. That refusal to deny my authenticity is what led to my place in history—provided I have a place in history.”

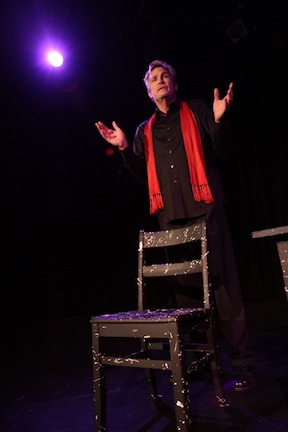

While Kearns’ corpus addresses many phases, topics, and themes, his performance art overall stands as a testament to survival. Pressing on against formidable antagonists, much of his success can be attributed to his clarity of focus and indomitable will. “Will and ambition are brothers,” he said. “I was ambitious to succeed—whether that meant as a boy-about-town or an actor-activist. I wanted to matter. I wanted to mean something.”

C. Todd White, author of Pre-Gay L.A.: A Social History of the Movement for Homosexual Rights, teaches anthropology at the Rochester Institute of Technology.