NEW YORK’S Metropolitan Museum of Art recently mounted an unusually large and comprehensive exhibition of drawings and writings by the Renaissance Italian master Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564). Among the scores of drawings in the exhibition, titled Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer (which closed in February), one group forms an exceptionally coherent and unprecedented ensemble of drawings that is only rarely gathered together.

Between 1532 and 1533, the 57-year-old Michelangelo gave six highly finished drawings on mythological and allegorical subjects to the art-loving young Roman nobleman Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, who was the great love of the painter-sculptor-architect’s long and often solitary life. Soon after they met in Rome, Michelangelo poured out his passionate desire for the exceptionally handsome, intelligent twenty-something in both visual and verbal arts. He showered Tommaso with dozens of love poems, often closely related in theme and imagery to the drawings. The Met’s wall labels and Web posts dealt more frankly and fully with the homoerotic significance of these works than have previous presentations, though space limitations precluded an in-depth analysis of this landmark achievement in queer self-expression.

Michelangelo’s dense cluster of gifts was doubly innovative. The so-called “presentation drawings” invented a novel genre: detailed, refined compositions that the artist gave only to his closest friends. These beautiful and elaborate works transformed drawings into an independent art form, not just for disposable preparatory sketches, and also into a medium for intimate personal communication. His poetry, too, was original and personal: the first substantial body of verses in a modern language addressed by one man to another. To find a voice for this passion, Michelangelo had to adapt and subvert the familiar tradition of love poetry from man to woman—epitomized by the verses of his literary hero, Francesco Petrarch, in praise of Laura—to address a male beloved.

Taken together, these drawings and poems are a multi-layered, achingly honest confession, both a celebration and an analysis of Michelangelo’s intense yet conflicted feelings for Cavalieri. The glimpses that this creative cornucopia gives us into the artist’s psyche, including his intense religiosity, foreshadow the arc of his life and career over his final decades.

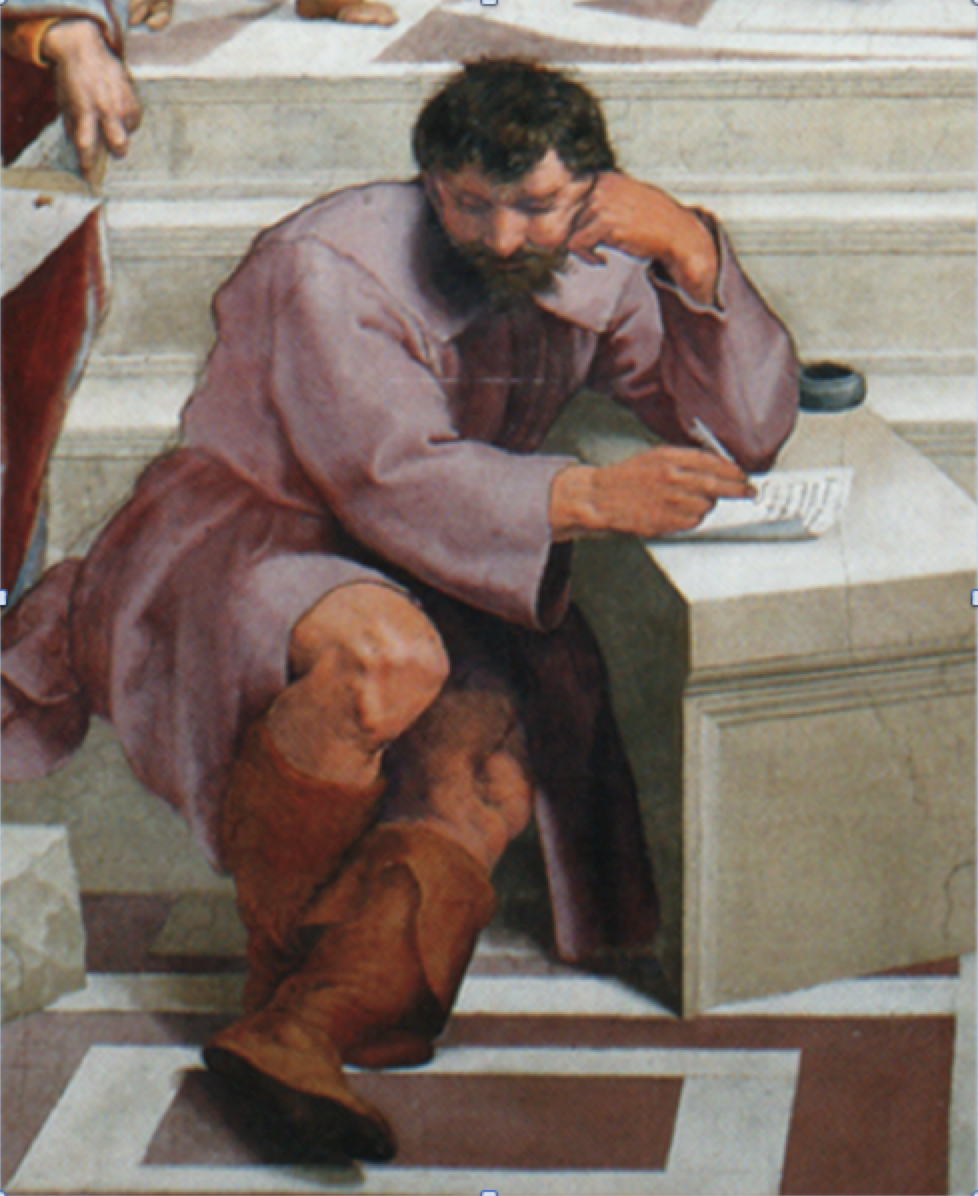

Few people today know that Michelangelo was a poet as well as a visual artist, but his contemporaries were well aware of his devotion to the written word. As early as 1510, his arch-rival at the Vatican workshops, the painter Raphael, depicted him in his fresco The School of Athens—a group portrait of their famous contemporaries dressed as ancient Greeks—as Heraclitus, the “gloomy philosopher,” writing on a sheet of paper propped up on a sculptor’s block (figure 1). Michelangelo could, of course, be cranky and depressive. One of his first poems, the autograph of which was displayed in the exhibition, complains about the discomfort of frescoing the Sistine Chapel ceiling, at the same time that Raphael was painting him into The School of Athens just down the hall. Like many sheets from Michelangelo’s hand, it combines writing and drawing, in this case a cartoon of himself craning his neck awkwardly backward almost ninety degrees to paint on the surface over his head.

detail of Michelangelo as Heraclitus.

Michelangelo was the first artist to be so deeply involved with words as well as pictures, and the greatest until William Blake in the late 18th century. For him, text and image were complementary weapons in his expressive arsenal: only visual imagery could capture the external beauty of one’s beloved, but it took the specificity of words to convey his or her inner qualities, the deeper reasons for emotional connection. I say “his or her” because Michelangelo did write to both men and women, and he gave drawings to both genders. But the Cavalieri gifts deserve special attention as the first such multi-media love letters, and as the first between men—an early landmark in the gradual emergence of minority voices that have flowered fully only in modern times.

The pictures and poems catalog a wide variety of responses to his infatuation for Cavalieri, from ecstasy to fear to concern for the two men’s public reputations. The first pair of images he sent illustrate his complementary themes: the positive and negative aspects of love, which can induce both joy and pain, rapturous delight and helpless terror.

Embodying the positive side of love is the handsome mortal shepherd, Ganymede (figure 2), who caught the amorous attention of Jupiter, the busily bisexual king of the gods. The first drawing (of which only a copy survives) depicts Jupiter swooping down to earth, disguised as an eagle, and carrying the youth up to be his heavenly cupbearer and lover. Love’s negative side is represented by the primitive giant Tityus (figure 3), who attempted to rape the goddess Latona, for which he was chained to a rock in the underworld, where a vulture perpetually pecked at his liver. His grisly punishment symbolizes the condemnation of uncontrolled or forbidden lust.

Presented to his beloved at the outset of their relationship, these paired drawings, and poems linked to them, announce the tragic ambivalence that Michelangelo suffered all his life toward love, toward the earthly beauty that stimulates it, and toward the created beauty of art. As he admitted to Tommaso in poem 76 (his autograph copy of which was in the show):

This, lord, has happened to me since I saw you:

a bitter sweetness, a yes-and-no feeling moves me; certainly it must have been your eyes.

Beyond the admiration of mortal beauty, deeper messages of the Ganymede drawing are revealed in related poems. Texts and images are closely intertwined, recalling the complementarity captured in the Roman author Horace’s phrase ut pictura poesis: a poem is like a painting, and vice-versa—two sides of the same psychic coin.

Although the young, beardless Ganymede would correspond more closely in age and appearance to Cavalieri, here he stands in for Michelangelo, who swoons in the transcendent grip of Tommaso’s godlike, inspiring beauty. In numerous poems, Michelangelo evokes that sense of exaltation, both physical and spiritual, through parallel images of wings and upward flight. This from poem 83:

I see in your beautiful face, my lord,

what can scarcely be related in this life:

my soul, although still clothed in its flesh,

has already risen often with it to God.

… every beauty seen here [on earth]resembles…

that merciful fountain from which we all derive [i.e., God];

…so he who loves you in faith

rises up to God.

In other words, Michelangelo not only delighted in Tommaso’s physical body, he regarded that sublime beauty as a reflection of God’s eternal perfection, an uplifting foretaste of heavenly joy. He imagines love as a ladder, on which the lower rungs of earthly beauty can inspire the lover upward toward a similar but more profound union with God. His love for Cavalieri is justified and ennobled by this spiritualizing function. In the drawing, we delight in the vision of a rapturous earthly emotion; in the poem, we understand its divine overtones.

Michelangelo’s theory of love grew out of the popular Renaissance philosophy of Neoplatonism, which attempted to reconcile Greek tradition and Christian values, often by finding allegorical interpretations of pagan myths, especially their erotic elements. An engraved copy of his Ganymede (figure 4), made to illustrate a book of moralizing emblems, shows how these philosophers recognized their ideas in Michelangelo’s image and appropriated these ideas to enrich their own tradition. To them, the name “Ganymede” derives from the Greek words for “enjoyment of the intellect,” and the mythic shepherd symbolizes the pure, innocent soul drawn heavenward by the love of God, while the dog below stands for base earthly desires left behind in that enraptured ascent.

Similarities of both form and content connect the Ganymede to another of the Cavalieri drawings, The Dream of Human Life(figure 5), which also illustrates Neoplatonic ideals about the soul’s ascent to the divine, aided by beauty. The thematic link is underscored visually by the central male nude, similar in body type and pose to Ganymede (four of the drawings feature variations of this same smooth-faced muscleman). The swirling, dreamlike figures around him represent the seven deadly sins, such as gluttony, avarice, and lust. A winged spirit, personifying beauty and chaste love, hovers over the youth with a trumpet, awakening him from worldly temptations to a transcendent spiritual life. It is difficult to find a precise, literal meaning for this complex allegory, but that was the point: presentation drawings were designed to provoke careful examination and learned discussion, another form of communion between donor and receiver. On a more poetic plane, however, it shares with The Rape of Ganymedethemes of the struggle between carnal and spiritual pleasures and the yearning to free the immortal soul from its temporary earthly prison.

The longsuffering Tityus represents the opposite pole of desire, the lust that expresses itself through the body, not the mind. Two kinds of pain overlap in this image: the externally imposed pain of punishment for illicit passion—a particularly resonant theme for a man loving another man—and the more internal pains any lover feels when his beloved is absent or unresponsive. The poems lament his sense of helplessness: he repeatedly calls himself a “slave” or “prisoner” of love who is “tortured” and “martyred” by frustrated desire. He even puns on the name of the man who inspires this bitter sweetness (in poem 98):

If, to be happy, I must be conquered and chained,

it is no wonder that, naked and alone,

I remain prisoner of an armed cavalier.

Two further drawings in the Cavalieri series delve deeper into other painful consequences of love. In The Archers, Cupid naps in the foreground while his surrogate army of bowmen aim their unseen arrows into a male herm, a carved symbol of eros and fertility. Arrows and darts were conventional Petrarchan metaphors for the hurtful pangs of desire; their fearful power is evoked in this sketch through a dozen Ganymede-esque nudes, all piercing the helpless male with a burning desire that’s also manifest in this poem (74):

Who else is there who lives only on his death,

As I do, on suffering and pain?

Oh, cruel archer, you know just the moment …

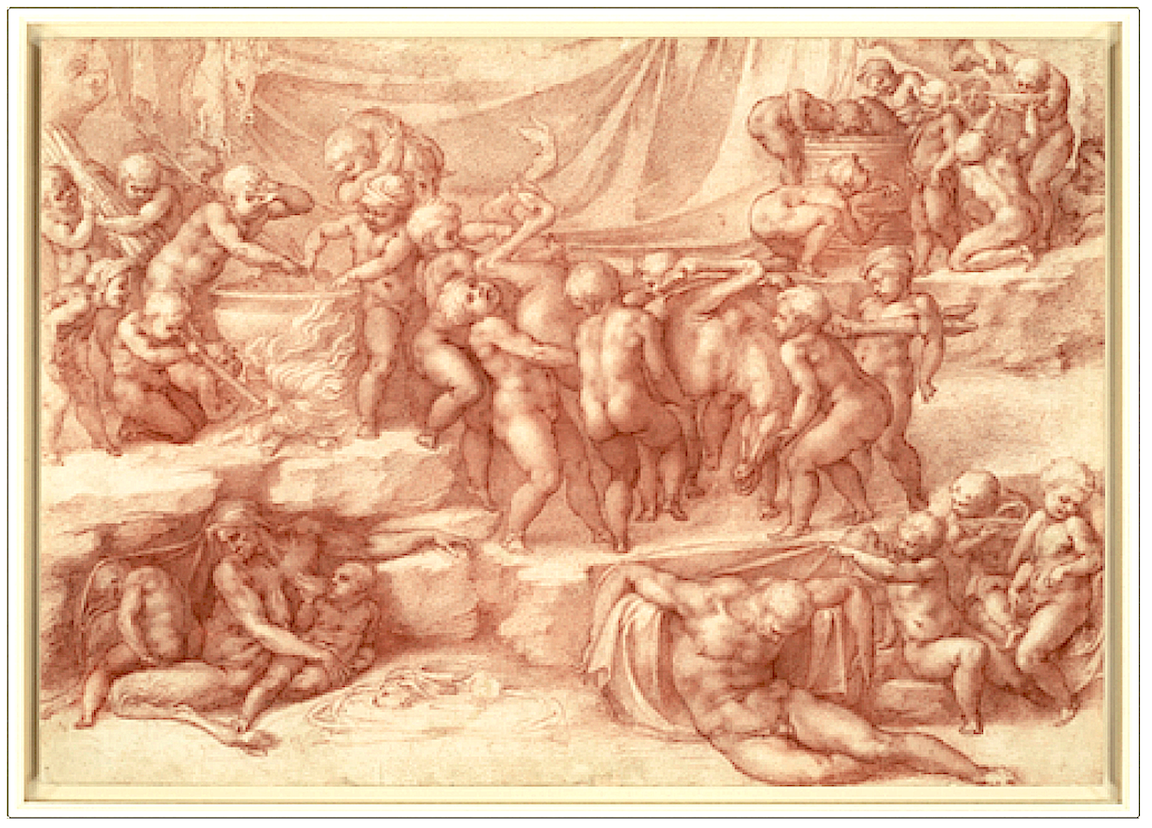

In the drawing titled A Bacchanal of Children(figure 6), Michelangelo depicts a crowd of uncontrolled, cupid-like infants indulging in riotous behaviors. One group at upper right drinks from a huge vat of wine, while one of them urinates into a dish. A group at left fan the flames beneath a boiling cauldron, while others struggle with a writhing wild beast. These creatures stand for bodily instincts, devoid of reason, animalistic, like the foreground figures, a half-goat satyr mother at the left, and a naked man passed out from drink.

This nightmarish fantasy encapsulates Michelangelo’s moral dilemma: he was torn between his desire for passionate union with another man and his deeply religious fear that such passion could get out of control. He felt guilt and self-doubt because the Christian culture he’d internalized labeled any physical intimacy between men as sodomy, condemned as both a sin and a crime. No wonder he defensively denied several accusations of sodomy and insisted in his poetry that his love was “chaste” and “honest.” When rumors about the purity of his intentions reached Cavalieri, a poem reassured him not to listen to such hypocrites, because (poem 83): “the evil, cruel, and stupid rabble/ point the finger at others for what they feel themselves.” Understandably, then, Cavalieri was anxious about public exposure of his love gifts. He wrote to Michelangelo after a powerful Medici cardinal insisted on having the drawings copied, lamenting that “I did all I could to save the Ganymede [from being copied].”

A final drawing, actually a series of three, highlights a more internal kind of fear: the anxiety a lover feels that his painful longing may be met with indifference or rejection. The sketchier first draft bears a written request to Tommaso either to send it back if he doesn’t like it, or to approve it for completion—suggesting that these compositions were not surprise gifts but rather, like the shared conversations about their meanings, something of a collaborative effort between creator and receiver.

Phaeton, a child of the sun-god Apollo, begged his father for permission to drive the great horse-drawn chariot of the sun, a herculean task for which the mortal adolescent was unfit (figure 7). Apollo regretfully consented, and, predictably enough, the arrogant youth careened wildly through the heavens until Jupiter, higher still, resolved the crisis by toppling Phaeton with a thunderbolt. The ill-fated youth’s sin is hubris—overweening pride and ambition—a vehicle for Michelangelo’s sense of presumptuousness in daring to “fall for” the godlike Tommaso. It is as if to say: I fear that my love for you may end only in frustration and tragic failure.

As with any romantic drama, we all want to know how it turned out in the end. Unfortunately, the Phaeton drawing was prophetic: Michelangelo’s ecstatic and terrifying passion gradually faded, as it had to, for reasons of official morality and class barriers. As his poems and pictures show, to Michelangelo and his contemporaries, the ultimate goal of this mortal life is to raise the inner soul toward an ecstatic union with God, not with humankind, regardless of gender. In this struggle, mind must triumph over matter, the spirit over the body.

The artist’s last forty poems do not address either love or art, except to disparage them as trivial pursuits, distractions from the quest for sanctity and salvation, which grew ever more consuming as the artist lived on into his late eighties. At the end of his life, he renounced both of his lifetime passions. He rejected art as “laden with error” and dismissed love as “gay and foolish,” concluding (poem 285):

Neither painting nor sculpture will be able any longer

To calm my soul, now turned toward that divine love

That opened his arms on the cross to take us in.

Though the arms of Ganymede gave way to those of Jesus, Cavalieri remained a lifelong friend, and even a colleague, completing Michelangelo’s designs for the Capitoline Hill in Rome and comforting him on his deathbed in 1564. His native city, Florence, staged a grand funeral. Among the large temporary canvases erected to commemorate his many achievements was one depicting Michelangelo crowned by Apollo and the Muses for his literary accomplishments. Now a long-bearded elder, he is still shown penning verses on paper, just as Raphael had portrayed him half a century earlier. His greatest fame remains his visual art, but his writing was a serious avocation, essential to appreciating his most personal visual works. Michelangelo knew his older compatriot Leonardo da Vinci, who was also a prolific writer; so perhaps he also knew, and certainly would have concurred with, Leonardo’s pithy declaration: “Painting is poetry that is seen rather than felt, and poetry is painting that is felt rather than seen.”

James M. Saslow is professor emeritus of art history at Queens College, CUNY, in New York City.