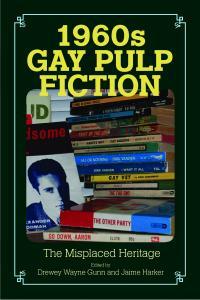

1960s Gay Pulp Fiction: The Misplaced Heritage

1960s Gay Pulp Fiction: The Misplaced Heritage

Edited by Drewey Wayne Gunn and Jaime Harker

U-Mass Press. 304 pages, $27.95

IN THE EARLY 1950s, the New York publishing company Greenberg was convicted of sending obscene materials through the mail. The publishers were fined and the books were effectively banned. The offending texts were three gay novels (none with explicit sexual content): Quatrefoil (1950), by James Barr; The Invisible Glass (1950), by Loren Wahl; and The Divided Path (1949), by Nial Kent. The federal government’s crusade against what J. Edgar Hoover (or his ghost writer) called “the tainted temptations of muck merchants” continued into the 1960s. In 1961 alone, there would be almost 400 convictions for the same offense. But a series of rulings by the Supreme Court in the late ’50s and early ’60s, plus the unprecedented accessibility—and visibility—of inexpensive pulp paperbacks, radically changed the rules of the game.

By the 1960s, new production and distribution technologies made gay texts and images widely available to the public for the first time. Unlike the Greenberg hardcovers of the ’50s, pulp paperbacks bypassed the conservative world of conventional publishing that relied on big-city bookshops, reviews in academic journals and major newspapers, and sales to libraries. Instead, cheaply priced books were displayed, covers out, on newsstands, at bus terminals and drugstores, and even at highway road stops in small towns. In 1960, eight books of gay fiction were published in the U.S. In 1969, there were 268, all but eighteen of them paperback originals! The unprecedented success of the pulps soon emboldened hardcover firms like Grove Press to publish gay authors, including John Rechy, William Burroughs, and Jean Genet.

The paperback explosion was driven by technology and changing public attitudes in the post-war era, but it could not have happened if gay publishers hadn’t challenged the laws. In his essay “Historicizing Pulp,” Whitney Strub points out that when the homophile magazine One fought a legal battle against the obscenity laws, it “persevered despite losing at every rung of the judicial ladder, successfully appealing to the highest court in the nation, even though it found little legal support, even from such free speech defenders as the ACLU.”

However varied their quality as literature, this new gay genre had an important effect. In the words of one commentator, “whatever their negative images or messages, they told us we were not alone.” In an era when Time magazine was denouncing homosexuality as “a pernicious sickness” that “deserves no encouragement,” widely distributed pulp paperbacks provided an alternative view. Along with the ’60s youth rebellion, they helped lay the foundation for the gay liberation of the ’70s. For example, the popular illustrated tour book A Summer on Fire Island (1968, Guild Press), provided what contributor Philip Clark calls “an innovative combination of fiction and reportage … an unusual look at life at the famous gay retreat … with the entire ending an extended argument for gay civil rights that prefigures the demands of the gay liberation movement.”

In his essay on Guild Press publisher H. Lynn Womack, Clark quotes John Loughery’s observation that “the role of books and writing in the development of an identity—prior to the age of television at any rate—has often been of special significance to marginalized groups. … For homosexuals, whose families and teachers are not likely to have much to say to them on the subject, the gay novels and plays encountered in adolescence and early adulthood can be vitally important and long remembered.” Clark provides fascinating information about Womack, a rather sketchy but brave porno publisher (“Poor taste that makes money is perfectly justified!”), who had the advantage of owning his own printing plant. Womack won a key Supreme Court censorship case and for a time ran his business from the confines of a mental asylum.

By the 1970s, with legal restrictions eased and gay subject matter no longer universally taboo, more authors were able to publish their work in hardcovers or trade paperbacks. At the same time, mass-market sales of popular gay fiction by authors like Patricia Nell Warren and Gordon Merrick soared. The way was open for more “literary” writers like Andrew Holleran and Edmund White.

1960s Gay Pulp Fiction contains twelve essays on various pulp writers and on aspects of the pulp phenomenon. A number of contributions focus on single authors: Samuel Steward (Phil Andros), Victor J. Banis, Richard Amory (author of the popular Song of the Loon and its sequels), Jay Greene, and Dirk Vanden. Philip Clark’s piece on Womack is a tantalizing introduction to an oddly neglected figure. Reed Massengill has an informative essay on Alexander Goodman (George Haimsohn), author of various gay-themed books and co-creator of the musical Dames at Sea. Jeremy Fisher writes about the 1965 Australian novel No End to the Way by Neville Jackson (G. M. Glaskin), pointing out that before the 1970s, Australia routinely banned all works that made reference to male homosexuality, even academic and scientific texts.

There are a few minor errors. The editors advance Gay Sunshine Press as the first gay literary press, though it was preceded by the Toronto-based Catalyst. James J. Gifford confuses pederasty with pedophilia, which is unfortunate. The index appears incomplete: there is no entry for the ACLU; while Grove Press is listed, Greenberg is not. But these are minor annoyances. Refreshingly, there is a minimum of academic jargon, though a few neologistic monsters like “narrativization” and “metronormativity” have crept in. An appendix provides notes on some of the more significant writers, including a useful guide to pen names.

1960s Gay Pulp Fiction will be of interest to both academic scholars and general gay readers and should be read in tandem with co-editor Drewey Wayne Gunn’s fully illustrated 2009 compilation The Golden Age of Gay Fiction.

Ian Young is the author of Out in Paperback: A Visual History of Gay Pulps (MLR Press) and Encounters with Authors (Sykes Press).