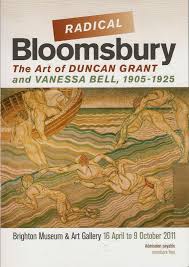

Radical Bloomsbury: The Art of Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, 1905-1925

Radical Bloomsbury: The Art of Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell, 1905-1925

Brighton Museum and Art Gallery,

Brighton, UK

April 16-October 9, 2011

IN NOVEMBER, 1910, a small but important art show opened in the Grafton Galleries in London. Titled Manet and the Post-Impressionists, the show was curated by Roger Fry, a member of the Bloomsbury group, a painter, art critic, and at different times the lover of Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell. This was one of the earliest shows in London dedicated to Impressionist and Post-Impressionist French art.

The critics were in general disgusted by the show as yet another sign of the decadence of the British Empire and saw it as a frivolous foray into French æsthetics. Post-Impressionist art, a term Fry coined, would soon be associated with labor unrest, anarchists, Irish demands for Home Rule, and the suffragettes’ increasing agitation for the right to vote. Just days after the show opened, suffragettes protested at the House of Commons while its members were debating the question of women’s rights. As Frances Spalding notes in her 1997 biography of Duncan Grant, the protest resulted in 117 arrests, which “set off a program of window-smashing, arson and bombs as the suffragettes, denied political power through the normal democratic procedures, resorted to violence.” Political protests and art controversies comingled that winter and created a moment about which Bell’s sister Virginia Woolf would later declare famously: “On or about December 1910 human nature changed.”