Derek Jarman

Derek Jarman

by Michael Charlesworth

Reaktion Books

202 pages, $16.95

DEREK JARMAN (1942–1994) is one of those artists whose interests were expansive and who had the creative powers not only to indulge them but to do so with distinction across a broad range of categories. When he died at 52 of AIDS-related illnesses, he could justly be remembered as an accomplished painter, poet, memoirist, set designer, movie director, and gardener. (Gardening, by the way, was not just a hobby—Jarman’s garden at his Prospect Cottage in Kent, England, earned praise from serious horticulturalists, and Jarman gardened throughout his life.) Consider this catalog of Jarman’s output, in addition to a large body of paintings: eleven feature films; nearly forty short films; roughly twenty music videos for the likes of the Pet Shop Boys and Marianne Faithfull; set designs for at least ten major plays, operas, and films; three full-length memoirs; a book of poetry; and a handful of other books, scripts, notebooks, and follow-up books for his many films.

Jarman’s reputation is helped by the fact that his major accomplishments were in film, a medium capable of reaching a large audience quickly. What’s more, at a time when many of his contemporaries stood by in silence, Jarman was among the first artists to embrace radical activism in response to the AIDS crisis. And so Jarman was producing groundbreaking cinema while also standing  front-and-center as a vocal critic of a government that wasn’t doing nearly enough to prevent the death and suffering brought about by AIDS. He was a highly public figure, and often a controversial one.

front-and-center as a vocal critic of a government that wasn’t doing nearly enough to prevent the death and suffering brought about by AIDS. He was a highly public figure, and often a controversial one.

By all accounts, Jarman’s early life was far from serene. While he was born into relatively comfortable circumstances, his family was not necessarily rich. His father was an RAF squadron leader, and the family moved frequently, as is often the case in military families. Young Derek was widely traveled by a very young age, having been to Italy and Pakistan, for example. Jarman’s father was given to violence, which he readily inflicted upon Derek and his sister. Jarman’s mother tolerated these outbursts, according to Jarman’s accounts, and did her best to keep the peace, but the Jarman household was a troubled one. Unfortunately for Jarman, his years at boarding schools were little relief from his difficult home life. Although he was able to explore his artistic interests and find creative support from a few teachers, he was not very popular among his peers, who typically favored those engaged in more athletic pursuits.

It didn’t help matters that Jarman’s dark, somewhat exotic looks earned him the nickname “wog,” a term with various racist overtones, which in turn increased the ostracism. Nor did it help when Jarman was found in bed with another boy, clearly enjoying himself. That incident provoked a very public punishment and set the stage for torments from his fellow students. On at least two occasions, Jarman was sexually victimized (once, in a full-on attack by a group of boys at his school and, later, when he was hitchhiking in Switzerland). Central to all of this was Jarman’s early awareness of his sexual difference. This eventually became a source of strength. In the course of his development as an artist, Jarman was encouraged not only by creative mentors but also by artistic heroes like Beat writers Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, who had very public identities as gay men.

In the 1960’s, Jarman was painting, writing poetry, and making a name for himself as a set designer for a wide array of dramas, ballets, operas, and other stage productions. In 1969, in a train departing Paris, he offered a seat in his compartment to a young woman who happened to be a friend of film director Ken Russell. This encounter eventually led to Russell hiring Jarman as the designer for his film The Devils. Jarman went on to design other Russell films, and he began his own experimentation with short films.

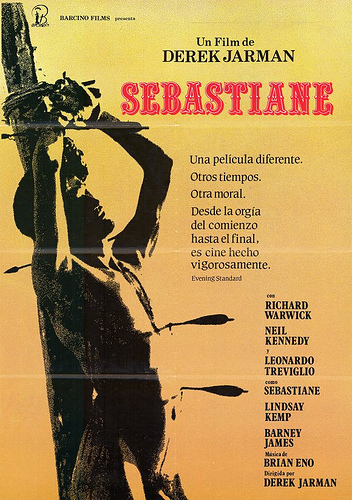

In the mid-1970’s, Jarman and a friend began planning a film about St. Sebastian. After a falling out, Jarman took over the project, and Sebastiane (1976) served as Jarman’s directorial debut. With dialog entirely in Latin, featuring ample male nudity, homoeroticism, and even spoken poetry, Sebastiane introduced Jarman as a clearly unconventional filmmaker. His next films, Jubilee (1978) and The Tempest (1979), confirmed that reputation and established Jarman as an important director. By the 1980’s, with films like Caravaggio (1986) and The Last of England (1987), Jarman had earned both fame and critical acclaim.

Michael Charlesworth’s Derek Jarman, recently issued as part of Reaktion Books’ Critical Lives series, is a concise critical biography of Jarman. In his preface to this slim book, Charlesworth acknowledges that Tony Peake’s Derek Jarman (1999), at 500-plus pages, is still “the last word” on Jarman’s life story. Charlesworth’s year-to-year account of Jarman’s life can seem rushed at times, but he skillfully weaves this information in with the artist’s creative evolution, particularly when detailing the terrible progress of Jarman’s illness.

He makes a strong case for reconsidering certain aspects of Jarman’s career, such as the widely held notion that he essentially abandoned painting for film. He contends, in fact, that Jarman helped redefine cinema through his exploration of the physical possibilities of painting. Perhaps Jarman’s triumph in this regard is his final film Blue (1993), which consists of a uniformly blue screen and a soundtrack of selected music, voice-over, recited poetry, and a variety of sound effects. He also gives due consideration to Jarman as a writer, arguing that this body of work deserves more attention. Charlesworth’s Derek Jarman is an admirably concise but comprehensive overview of the life and work of a truly prodigious creative spirit.

Jim Nawrocki, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a writer based in San

Francisco.