On Sondheim: An Opinionated Guide

On Sondheim: An Opinionated Guide

by Ethan Mordden

Oxford University Press

198 pages, $27.95

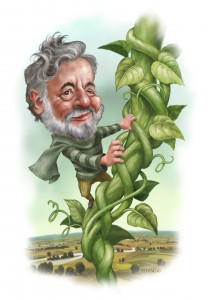

IF ANYONE has earned the right to be opinionated about the work of Stephen Sondheim, it’s Ethan Mordden, America’s foremost historian and connoisseur of musical theater. Mr. Sondheim, in turn, has held sway over musical theater itself as a composer and lyricist over the past sixty years, starting with his words for the songs in West Side Story and Gypsy and continuing with both words and music for more than a dozen shows, including Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, Sweeney Todd, Sunday in the Park with George, and Into the Woods.

These works are part of the long tradition of the New York musical stage, and Ethan Mordden, author of twelve previous volumes on Broadway musical history, expertly situates Sondheim’s creations in this larger context, where their importance looms large. Sondheim’s shows broke with tradition and advanced a whole new genre, what has been called the “concept musical” (though Mordden points out the slipperiness of this term as used by various commentators). He also shows that even Sondheim’s boldest experiments can be traced back to the work of his artistic forebears, including Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein II, whose Allegro (1947) pioneered—for the musical, at least—the elastic sense of time and space and other non-realistic elements that are now quite familiar to audiences.

After introductory surveys of Sondheim’s career and influences, Mordden devotes a short chapter to each of his shows, closing with a review of “Sondheim on Film” and suggestions for further reading and listening. He has thought deeply about Sondheim’s musicals in terms of their æsthetic craft and their themes, which he explicates in a breezy, mostly accessible style that gives him room to ramble and gossip. Thus the chapter on Company includes both an analysis of the show’s Pinteresque aspects and a glimpse into the love life of gay actor Larry Kert, who played Robert, the main character.

Sondheim’s own romantic affairs receive only passing attention, if only because Mordden is focusing here on the art; and he largely resists the urge to find autobiographical hints in the musicals’ characters or lyrics. He makes note of Sondheim’s initial reluctance to reveal his gay identity publicly, and he interprets even this from an artistic angle, arguing that coming out might have undermined the reception of the songwriter’s work: “Wouldn’t Gay Sondheim create a rival ‘text’ overshadowing Sondheim the composer or Sondheim the arts revolutionary?”

Sondheim’s own romantic affairs receive only passing attention, if only because Mordden is focusing here on the art; and he largely resists the urge to find autobiographical hints in the musicals’ characters or lyrics. He makes note of Sondheim’s initial reluctance to reveal his gay identity publicly, and he interprets even this from an artistic angle, arguing that coming out might have undermined the reception of the songwriter’s work: “Wouldn’t Gay Sondheim create a rival ‘text’ overshadowing Sondheim the composer or Sondheim the arts revolutionary?”

Describing Sondheim as “a classically trained composer who chose the theater over the concert hall and Broadway over the opera house,” Mordden points out classical influences everywhere in the master’s scores, from his evocations of Brahms and Ravel in A Little Night Music to the intricate development of melodic cells in Merrily We Roll Along. As a writer of lyrics, Mordden says, Sondheim thinks like a playwright, crafting lines that help create character and move the plot forward. Here he shows the influence of his mentor Oscar Hammerstein, who virtually adopted the young Sondheim after his father abandoned the family when he was ten, teaching the boy the art of writing lyrics and later guiding him to his first jobs in the theater.

Yet even the Hammerstein model was just a starting point for Sondheim, as Mordden contends in a fascinating discussion of form and realism in the musical. Hammerstein and his collaborator Richard Rodgers perfected what Mordden calls the “Extremely Integrated Musical,” in which every element—script, song, dance, design—blends smoothly into a lifelike narrative flow. Considered innovative in the early 1940s, that kind of cohesiveness soon became standard. But, as Mordden sees it, Sondheim and many of his contemporaries have “pulled away from the Rodgers and Hammersteinian unities,” demoted linear narrative, and embraced disjunctions and interruptions in their shows. “Life isn’t integrated,” Mordden observes, “why should art be different?”

It’s no surprise that Mordden, with his keen appreciation for Sondheim the lyricist, enjoys language, and his own use of it is varied, even playful, incorporating both academic and colloquial speech with rarely a slip-up. One of these occurs in the book’s closing paragraph when, glancing back at the start of his subject’s career, Mordden can’t resist tossing in a zinging reference to Walter Kerr (who didn’t like a few early Sondheim songs) as a “homophobic-shithead critic.” The homophobic part may be accurate, but the expletive sours the ending of a book that is otherwise generous, insightful, and entertaining.

Stephen Kuehler is a research librarian in Cambridge, Mass.