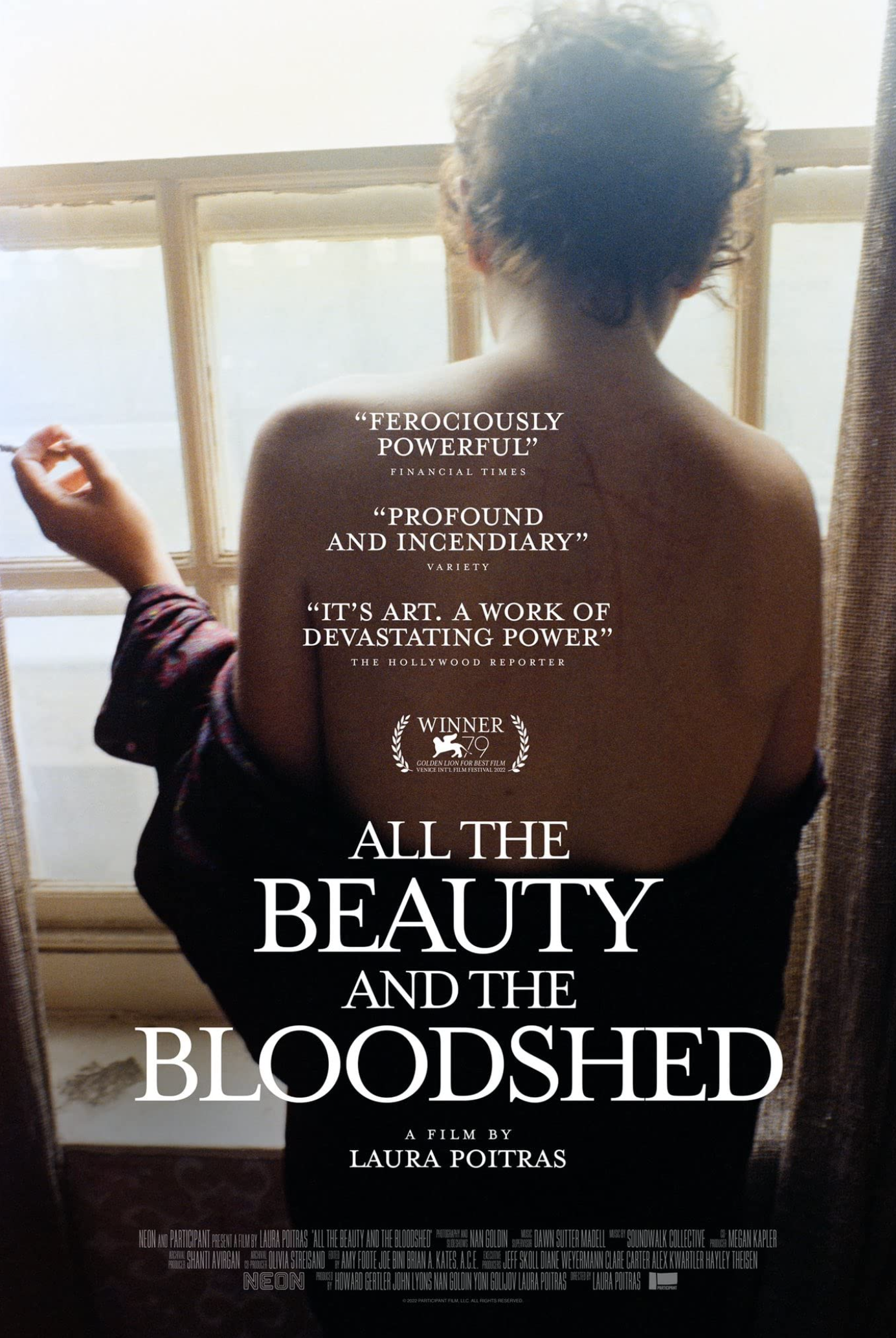

ON MARCH 10, 2018, a cadre of activists from the organization Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (PAIN), which was founded by photographer Nan Goldin, entered the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and proceeded to the gallery that houses the Temple of Dendur. The ancient Egyptians used the Temple for rituals in which the community could offer food, drink, and clothing to a resident deity. The activists likewise brought an offering as they formed a chorus line at the edge of the reflecting pool in front of the Temple and, in choreographed synchronization, opened their backpacks, which contained a thousand empty orange prescription bottles labeled “OxyContin prescribed to you by the Sacklers.” They tossed the bottles into the water and unfurled several black banners with the slogan “Shame on Sackler” while chanting “Shame.” This scene in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed is about protesting the Sackler family, whose pharmaceutical company Purdue Pharma made and marketed OxyContin, the brand name for the opioid Oxycodone.

Introduced in 1996 for pain management, OxyContin is more than twice as potent as morphine. It carries a high risk for addiction when taken in large doses or combined with alcohol or illicit drugs such as heroin or cocaine. The Sacklers aggressively marketed OxyContin with total disregard for its addictive properties. They concealed information about the abuse of OxyContin, even knowing that the pills were being crushed and snorted, stolen from pharmacies, and prescribed by doctors who were selling prescriptions. In a 2018 The New York Times article, “Origins of an Epidemic,” Barry Meier reported that the George W. Bush administration had blocked felony charges against Purdue Pharma despite a four-year investigation by the Department of Justice that concluded that Purdue had made billions while creating a national epidemic. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): “In 2020, an average of 44 people died each day from overdoses involving prescription opioids, totaling more than 16,000 deaths. Prescription opioids were involved in nearly 24% of all opioid overdose deaths in 2020, a 16% increase in prescription opioid-involved deaths from 2019 to 2020.”

Goldin is one of the documentary’s producers and its principal protagonist. The film thematically weaves together two complex narrative strands: her personal story and the protest against the Sacklers. The latter takes place against the backdrop of images from The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (1985), her autobiographical slide show set to music that became a cultural touchstone of the 1980s and elevated Goldin to prominence as a photographer. Her work is described as “felt photography,” which Roland Barthes defined as “affective intentionality” linking personal feelings and photography’s capacity to arouse emotions. She said the slide show was how she retained deep visceral contact with loss, asserting that images function as memory and are talismanic: “The slide show’s very much about loss.” It serves as a balladic memorial to the lost generation of her tribe from New York’s downtown subculture decimated by the AIDS pandemic.

Susan Sontag wrote in On Photography, “Through photographs, each family constructs a portrait-chronicle of itself—a portable kit of images that bears witness to its con- nectedness.” Throughout the documentary, there’s the clicking sound of a slide carousel, projecting snapshots in black and white, light-leaked Polaroids, streaked, dog-eared self-portraiture, family members, friends, drag queens, and her older sister Barbara, who committed suicide as an adolescent, and whose presence haunts Goldin’s life. Indeed, the documentary title is taken from a psychiatric evaluation of her sister during an institutionalization.

Goldin’s photography and the documentary confirm the relationship between representation and intimacy. She is never a stranger to the LGBT community. In an interview in the photography magazine Aperture, “The Ballad of Nan Goldin: A Conversation with Darryl Pinckney,” she said: “The lesbian community in Provincetown at the time was very small, and all the women were fucking each other, which made it interesting. I fell in love with a woman and obsessively photographed and filmed her for a long time, even after she broke up with me. I guess that was the beginning of what drove me to photograph people.” Of her sexual orientation, she said: “I’ve always been able to live with ambivalence.”

Goldin acknowledges that ACT UP is the model for her style of activism. She and PAIN have been successful, with several significant victories. In 2019, the Louvre removed the Sackler name from its walls, becoming the first major museum to erase its public association with the philanthropist family linked with the opioid crisis in the U.S. In December 2021, the Met in NYC removed the Sackler name from seven exhibition spaces, and five months later, the Guggenheim erased the family’s name from an education center. Purdue Pharma filed for bankruptcy in September 2019, facing 614,000 claims filed by individuals, municipalities, hospitals, tribes, and states, accusing the company and the Sackler family of contributing to a public health crisis with about 500,000 deaths since 1999. Purdue Pharma paid $500 million to claimants and was dissolved. For a decade before the bankruptcy, the Sacklers withdrew more than $10 billion from the company, distributing it among trusts and overseas holding companies. Economists estimate the cost of the opioid epidemic, including law enforcement, healthcare, and treatment, to be in the trillions.

The leading cause of death for Americans aged eighteen to 45 is a fatal overdose of fentanyl. Goldin noted: “Fentanyl is in all the drug supply now.” Within a year of PAIN’s formation, its mission shifted to one of harm reduction. In one scene, she’s learning how to operate a machine to analyze the presence of fentanyl in drugs (PAIN had raised $35,000 for the device). Fentanyl test strips (FTS) provide essential information about fentanyl in the illicit drug supply so users can take steps to minimize the risk of overdose. Narcan, a naloxone nasal spray that’s now approved for over-the-counter sales, can swiftly and easily reverse an opioid overdose.

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed has relevance for the LGBT communities in its attention to the legacy of ACT UP, harm reduction strategies, narratives about NYC’s downtown subculture, the AIDS pandemic, the complexity of sexual orientation, and performative activism. Apart from the theatrical aspects of ACT UP, another legacy of AIDS is harm reduction strategies that were developed, from safer sex to needle exchange. Research on opioid misuse in LGBT populations is inadequate. In one study, nearly twice as many adults in those populations misused opioids as in the general population. The LGBT community has been targeted by predatory individuals who have administered fentanyl in gay bars to cause incapacitation so as to commit robbery and murder. In April 2023, two individuals were arrested and charged with murder in connection with a series of killings and robberies.

The bankruptcy court hearing documented in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed included Goldin’s testimony and that of others who’ve been devastated by opioids and the Sacklers’ disregard for human life. For the record, among those who didn’t testify are two sets of lesbian parents separated by thousands of miles, both grieving the loss of an adopted adult son due to an overdose of fentanyl-laced drugs: Arlene Istar and Sundance Lev in Albany, whose son Shaiyah died in 2016 at age 21; and Sylvia Allen and Martha Shelley in Portland, whose son Solomon died in December 2022.

Steven F. Dansky, an activist and documentarian, is a frequent contributor to The G&LR.

Discussion1 Comment

Thank you, brother, for this review. It is informative, beautifully written and historically relevant to the present day. Now in my 60s I am disturbed by the ahistorical American mind in general. That you and Ms. Golden connect the tenor and activism of the early AIDS pandemic to contemporary culture is critical to understanding not only part of Golden’s life but also the magnitude of the addiction crisis and the power of community activism. Well done.