“SEX HAS ALWAYS BEEN the favorite topic of every intellectually cultured person I’ve known. The favorite topic for every unintellectually cultured person I’ve known is Books, or, what is worse, Music.” I’m thinking of these words, from a 1952 entry in his Paris Diary, as I ring the bell to Ned Rorem’s Upper West Side apartment on a late, gray winter’s afternoon.

Yes, I remind myself, we’ll talk about sex, but I also want to talk about books and music, Rorem’s books and music. It’s a prodigious body of work. His corpus of music includes symphonies, concertos, operas, keyboard works, chamber pieces, choral music, and songs, lots and lots of songs. How can we not talk about all this music? And the books—eighteen at last count—comprising several volumes of essays and six volumes of diaries—spanning the years 1951 to 2005—which Edmund White once referred to as Rorem’s “long peacock tail of memories.”

Yes, I remind myself, we’ll talk about sex, but I also want to talk about books and music, Rorem’s books and music. It’s a prodigious body of work. His corpus of music includes symphonies, concertos, operas, keyboard works, chamber pieces, choral music, and songs, lots and lots of songs. How can we not talk about all this music? And the books—eighteen at last count—comprising several volumes of essays and six volumes of diaries—spanning the years 1951 to 2005—which Edmund White once referred to as Rorem’s “long peacock tail of memories.”

“No writer has composed, and no composer written, better than Ned Rorem,” gay poet J. D. McClatchy writes in the Foreword to A Ned Rorem Reader (2001), an anthology published by Yale University Press, which won an ascap-Deems Taylor Award for musical writing.

Rorem buzzes me up. I have taken care to arrive not a minute earlier than our four-thirty appointment. I don’t want to risk annoying him in any way. He’s got a reputation for being prickly. But which Rorem will I meet? Has age mellowed this former golden boy of the composing world, at one time one of the most distinguished, outspoken, and, according to many, most self-centered artists of his day? Can we find anything to talk about that he hasn’t already said—brilliantly, maddeningly—in all of those books? I’m terrified that I’ll bore him.

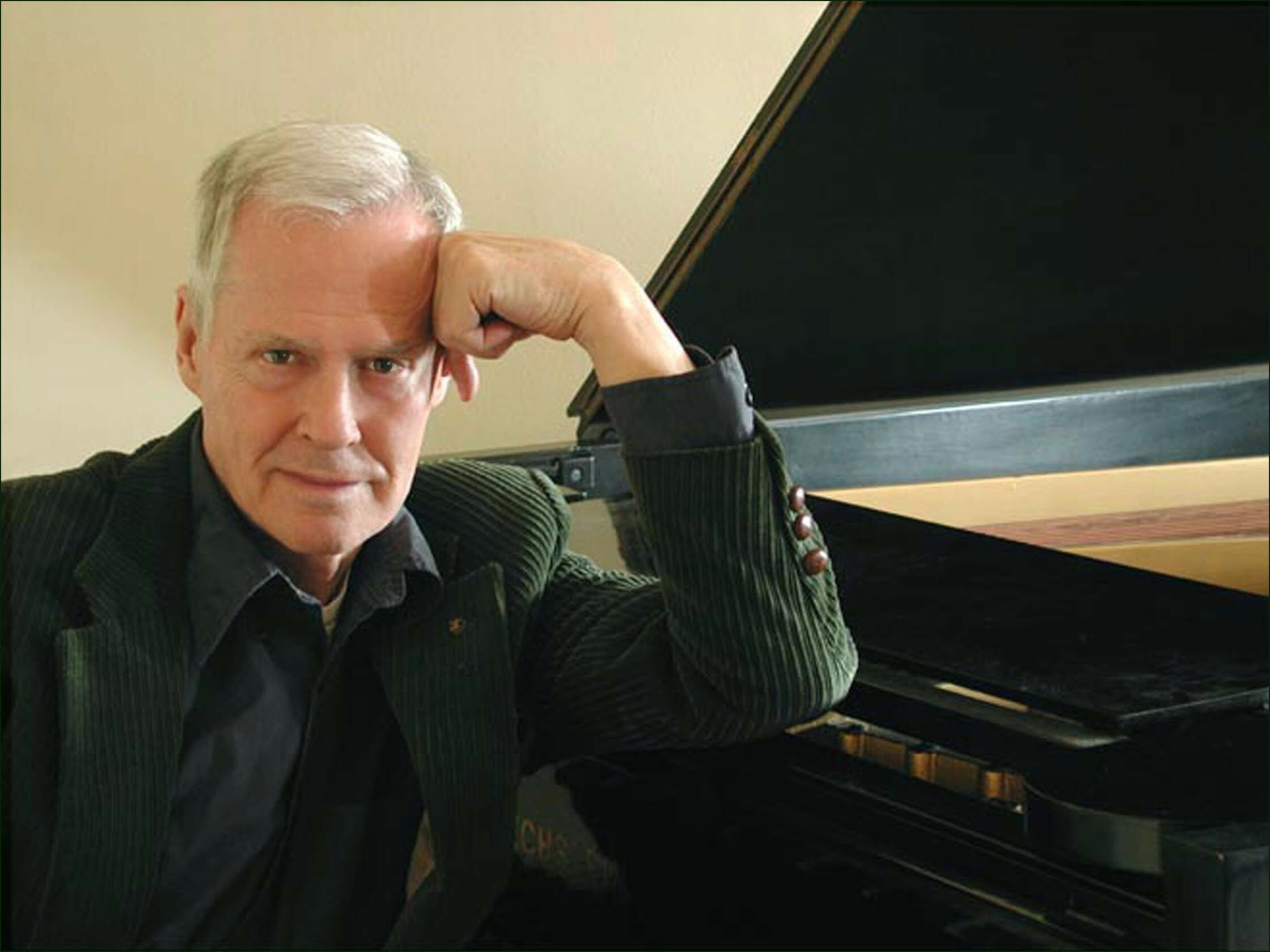

Rorem’s greeting puts me at ease—his handshake is warm, his smile kindly, the blue eyes of his Norwegian ancestry still arresting. He’s dressed casually, in slacks and a robin’s egg blue cardigan over a white tee shirt. The breathtaking beauty of his youth has faded, but in his mid-eighties he’s still winningly handsome. He invites me into the living room, where we sit down on adjoining sofas, in front of which, on a coffee table, he has laid out a plate of crackers and cheese and two sherry glasses holding what looks like water. (An outrageous drunk during his years as the enfant terrible of Paris and New York, Rorem has been sober for over forty years.)

“Are these things working?” he asks, nodding toward the two little digital recorders I’ve set down in front of him. “Sometimes I’ll sit an hour for an interview and then the person will go down into the street and call up to say, ‘Can we do it again?’ That’s happened more than once.” His voice, more soft-spoken than I’d imagined, still retains the clear enunciation of his Midwestern upbringing. And so we begin.

Rorem was born in 1923 in Richmond, Indiana. His parents were liberal Quakers, “not for reasons of God,” he tells me, “but for reasons of pacifism. We never talked about God.” When he was less than a year old, the family moved to Chicago. There, as a boy and later a teenager, his precocious preoccupations—a keen ear for music, a ferocious passion for bird collecting, and a craze for Catholicism—set him apart. “I was very attracted to the Catholic religion because it had a lot of superficial claptrap. It hit all the senses—you can smell it, eat it, hear it, and speak it.”

His other, more lasting, attraction was for all things French. As an avid piano student, even while he dutifully learned the Beethoven sonatas, Rorem tells me he “didn’t swoon.” But swoon he did over Debussy and Ravel. “I took to them like a lamb to slaughter.” He recalls hearing Debussy’s L’Isle Joyeuse at the age of ten or twelve: “And my life changed completely. I didn’t know people wrote things like that. I got all the Debussy preludes and learned them.”

Remarkably, once he’d figured out he was gay, at around age fifteen (when, instead of doing his homework, he was “discovering love as thoroughly as I ever will”), Rorem never felt guilty. “I was gay and so what? I just admitted it. I wasn’t on a soap box. But why pretend to be something I’m not? I told my parents, and they said okay.” Sophisticated and exquisitely handsome (“I used to take my own breath away,” he once wrote), Rorem was “one of the stars” in high school, popular at the dances. “I went with a girl. We were good dancers. If it was a formal dance, we wore sweaters; if it was an informal dance, we would get dressed up. We were contrary!”

In addition to piano lessons, the young Rorem took up composition. “I wrote pieces very early, and I’d play them for my first piano teacher, Margaret Bonds, and she would take them down like a secretary. She said, ‘You’ve got to learn to notate your own music.’” He took the advice to heart, traveling once a week after school into Chicago’s Loop to study harmony with Leo Sowerby, one of the foremost American church music composers of the day. “My family didn’t discourage me from a creative life. Father said, ‘How do you expect to make a living?’ And I said, ‘I don’t care whether I make a living or not.’”

After high school, Rorem enrolled at the Music School of Northwestern University, where he studied with Alfred Nolte, a protégé of Richard Strauss. Two years later, in 1943, he moved on to the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, one of the most prestigious music conservatories in the country. “I didn’t learn anything,” he tells me. His composition teacher was “an old fart, who assigned me to do all sorts of counterpoint lessons and I’d had all that. But I met a hell of a lot of people, people of distinction, whom I still know and like.”

During that academic year, World War II was in full force. Although a pacifist, Rorem was not formally a conscientious objector. Nevertheless, he was disqualified for service because of nearsightedness, flat feet, and “insufficient maturity” for the army. He spent a fair amount of time venturing into New York “to get drunk and get laid.” After Curtis, he moved permanently into New York—his apartment was on West 12th Street—where he worked as a copyist for composer Virgil Thomson, in return for twenty dollars a week and lessons in orchestration.

“Virgil was the most articulate person I ever learned from. Mostly you learn from yourself and from copying other composers. Virgil taught me not composition but orchestration. He did it in a very systematic way. First we’d study the flute, then the oboe, then flute and oboe together. Every combination imaginable. I don’t think you can teach a creative art. You learn that by copying, doing what your predecessors did. You’ve either got it or you ain’t.”

After his tenure with Thomson, Rorem transferred to Juilliard, where, in 1946, he completed his bachelor’s degree, then stayed on to do a master’s. During the two summers of his master’s program, he received fellowships to attend the Berkshire Music Center at Tanglewood, where he studied with Aaron Copland. “I can’t remember a thing Copland said—there wasn’t much he could say to me—but I studied his scores inside out. I’ve been influenced by everyone, but I don’t like to credit any one teacher.” Upon completing his master’s, Rorem won the Gershwin Award for Orchestral Overture. His song “The Lordly Hudson,” set to a text by Paul Goodman, was voted the best published song of 1948 by the Music Library Association. He was now 25 and in the middle of the decade he once described as “my years of deciding who I was.”

Deciding who he was included a trip to France in the summer of 1949. It was a “displacement,” as he termed it in his Paris Diary, that left him feeling new. And eager to meet le tout Paris. “People always said that I was so at home in France. It’s not that I went to France; I was always French. I went home. They took to me as much as I took to them, in every way. I got along very well with the French, first of all because I was awfully cute, and I was very well versed in French literature. I wasn’t just hanging around. I could talk about almost any French writer.”

One of his first introductions was to the French composer Francis Poulenc, who was openly gay and whose reputation as “half bad boy, half monk” must have resonated happily with his young American counterpart. According to his New York Diary, Rorem was embarrassed to show Poulenc his “little pieces” because he felt them to be “too outrageously French, too lush, too self-indulgent.” Ironically, Poulenc thought they were just the opposite: too careful, Nordic, unsensual. “To him,” Rorem tells me, “I was always a young kid. He was always the maestro.”

At the end of the summer, Rorem decided to stay on in France. That fall, at the opera, he met “a woman who was rich, intelligent, talented, and famous.” It was Marie Laure, the Vicomtesse de Noailles, one of the foremost Parisian patrons of the arts, who made it part of her profession to give and attend parties. She became the most important person in Rorem’s life during his years in France. Every day, at her house on the Place des États-Unis—“the most beautiful house I ever saw in my life,” he once told John Gruen—he “met the crowned heads of the whole art world at lunch, unless I had a hangover,” he tells me. His friendship with Marie Laure—a love affair of sorts—provided him with a potent cocktail of patronage, freedom, coddling, and connections, a mixture that further released his prodigious creativity.

In Paris, Rorem began to study composition with Arthur Honegger. “I was in a class in which I was the best. I don’t remember anything Honegger said”—this is getting to be a leitmotif, I see—“but I liked him a lot.” Eager for something new again, he went to Morocco, where he stayed for two years, working hard on his compositions. By 1951, when Rorem returned to Paris, he had composed, orchestrated, and “beautifully copied in India ink” a symphony, a string quartet, a piano sonata, a violin sonata, an opera, a piano concerto, five song cycles, fifty songs, three ballets, choral music, among many other pieces. He had also won a Fulbright and fallen in love three times.

Rorem remained in France until 1957, by turns prolific and profligate, and worrying that he was “growing into being an established lesser composer.” Thomson eventually cajoled him into returning to the States. “Virgil said, ‘Come back to America and start your career.’ He thought I was taking the easy way out. He meant that the French had enough problems without taking me up. That sort of gave me a turn.”

Back in New York, Rorem discovered that he was able to make a living as a serious composer. His Third Symphony was premiered by Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. He was awarded a Guggenheim, and he got a professorship at Buffalo “at a very good salary.” At the same time, his diary entries of that period—he was now in his mid-thirties—speak of ennui, excessive drinking, unhappy affairs, and rampant promiscuity. His days were divided—“too divided,” he wrote in August, 1958—“between sociability and creation.”

“The reason to drink was to get drunk,” he explains to me. “It was from the very beginning. I took to it like a duck to water. I was never not drunk. Nobody believes it, but I was really very shy. If you drink a lot, you’re less shy. Because I was cute, people paid attention to me, and so I drank more than I should have. I stayed out later than I should have. Finally, I said to myself, anyone can get drunk, but only I can write my music. When I finally stopped drinking, which is easily 45 years ago, I stopped. I haven’t had a drop of anything, not even one martini. I’m not even tempted to.”

During the 1960’s, Rorem garnered important commissions and awards. He served as composer-in-residence at the University of Buffalo and the University of Utah. There were premieres of several important works, including his opera Miss Julie. He also began living with James Holmes—“a young Carolina musician,” he noted in the pages of his 1967 diary—and the man with whom he would make a home for the next 32 years. All the while, he continued to write songs, an outpouring that prompted Time magazine to declare in 1965 that he was “undoubtedly the best composer of art songs now living.”

Many of the poets that Rorem has set to music—Auden, Witter Bynner, Whitman, Paul Monette, Mark Doty, Elizabeth Bishop, Paul Goodman—have been gay, though he tells me that he didn’t choose their texts for any explicit gay message. “I’m not a flag waver,” he says. “I don’t beat a drum.”

That may be true, but in 1966, when he published the first volume as The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem, he achieved overnight notoriety as one of “America’s three unapologetic queers.” (The other two, according to him, were Paul Goodman and Allen Ginsberg.) Covering the years 1951 to 1955, the diary revealed Rorem’s unabashed zest for dropping names, divulging affairs, describing debauchery, and generally portraying himself as the cynosure of all eyes. The enfant terrible became a cause célèbre. Hortense Calisher, for one, called the diary “bitchy” and “in bad taste.” Subsequent volumes only upped the ante. “I’m a narcissist,” Rorem tells me when I bring all this up, “but everybody is chiefly interested in themselves anyway. I just admit it.”

In recent years, Rorem has had second thoughts about the candor of his diaries. “I have found that if you write about real people, no matter who you are, someone is going to object. I’ve lost two friends from the diaries. One is the wife of George Perle. She was my best girlfriend. We’re civil now, but she objects to things that I said. But if it’s a question of should I withdraw it, well, if I withdraw it, there’s no diary. Certain people always say, ‘Oh, I was there too but it didn’t happen that way.’ A diary is a chancy thing.”

I’m curious to know which of his 600-plus songs is his favorite. “If I died right now, I think Evidence of Things Not Seen”—his cycle of 36 songs, written for four solo voices and piano in 1997, when he was 74. “As an oeuvre. I wouldn’t want to take any one song out of there.” Is that where he declares everything that he knows about song? “I declare that in every song.”

Strangely for a composer so universally praised for his songs, Rorem won his only Pulitzer Prize for an orchestral suite, Air Music, in 1976. “That’s interesting, isn’t it? Everybody has said the same thing. The Pulitzer people like big things. Air Music was a big orchestral piece. I account for it in that people who give out those prizes like size.”

Rorem is frequently called an American romanticist composer, one who early on disavowed the lure of atonality. In Paris Diary, he wrote, “The twelve-toners behave as if music should be seen and not heard.” What, I ask him, was his objection to adopting the new tonal system? “Even today I don’t know what ‘new’ is, but I think that trying to be new is completely unimportant, utterly. Lou Harrison in about 45 minutes taught me the whole secret of twelve-tone music. I wrote like that for about a week. I wasn’t attracted to it. Certain twelve-tone pieces—Pierre Lunaire, the Berg violin concerto—I’m attracted to, but complexity for its own sake bores me. Elliot Carter, for example, I don’t even know why he’s famous.”

In 1996, Rorem participated in Joseph Dalton’s “Gay American Composers” project for CRI (Composers Recordings, Inc.), with four selections from his The Nantucket Songs (1979). In the liner notes to that CD, he wrote, “Music is the one art whose maker’s [sexual]orientation cannot be deduced.” What, then, does he make of recent scholarship which seems to suggest otherwise? “I think it’s bullshit. I heard somebody lecturing saying something about a male homosexual being feminine in a way. What kind of music is feminine as opposed to masculine, or neuter? I think that’s something to write an essay about, but it doesn’t prove anything. Music is what the composer is, if he’s a good composer.”

In a published exchange with Lawrence Mass, co-founder of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, Rorem has said that he doesn’t think homosexuality is a very interesting subject, except politically. Does that mean that he wouldn’t be interested in writing an opera with an explicitly homosexual character? “If I did, it wouldn’t be because they were homosexual but because they were part of life. Because it’s good theatre.” For a while, Rorem did, in fact, toy with the idea of doing a gay-themed opera. He considered Whitman, Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask, a Ganymede opera, Joe Orton’s plays, Proust, which “would certainly tempt me,” he told Mass. I ask him if the temptation still holds. “No, because he’s too personal for everybody. We all know him and I wouldn’t know how to cut him down to size. If I did a gay opera, I wouldn’t do one that was problematic—someone who commits suicide because their mother finds out—that’s a little passé. But I’m not against one of the characters being gay. I’m a homosexual 24 hours a day. As I said, I don’t wave a flag about it.”

Nevertheless, he has written extensively about his homosexual life, not only in the diaries, but in other published pieces as well. One of the most delightfully outrageous was an essay he wrote in 1967 about going to the baths in New York. Funny, wise, graphic, elegant—it’s quintessentially Rorem. “I still go,” he tells me when I remind him of the essay. “I may even go today. I like the anonymity of it. Every once in a while someone will come up and say, ‘Are you Ned Rorem?’ I don’t like that. Sometimes I’ll go for as long as two hours and virtually nothing happens. I’m not 23 anymore.”

When Holmes, his companion of over thirty years, died in 1999, Rorem stopped composing for a while. Depression and insomnia became “daily companions.” Thoughts of suicide entered the diary. “When Jim died, I became a different person. For a while I thought, What’s the point of writing music? What’s the point of art? But art is the only point.”

Where does he think high art music is going today? “I wouldn’t have thought this even twenty years ago, but most people don’t care, and never will, about the arts. I’m talking about educated adults. But enough do. That’s what the situation is. There’s a lot of interesting American music today. I don’t know why, because America doesn’t encourage the arts. The government isn’t against the arts; it doesn’t know the arts exist at all. We’re musically the most interesting country in the world today, including Japan and China.”

As far back as 1957, Rorem was struggling with the “terror of being forgotten.” Does he still struggle with that fear? “Yeah. Why do we live if we have to die? We think everything goes except ourselves. I still don’t think I’m going to die. No one can imagine his own death. When we stop to imagine it, we always see ourselves as survivors, Freud says. If we have to die, we should be remembered in some way or other. I stick to that.” Does he have any regrets? “The French have a saying: ‘I have remorse, but no regret.’ I’m me and, whatever that is, I can’t be better or worse now. I think I’ve done everything I’ve wanted to.”

Phil Gambone’s latest book is Travels in a Gay Nation: Portraits of LGBTQ Americans from the University Wisconsin Press.