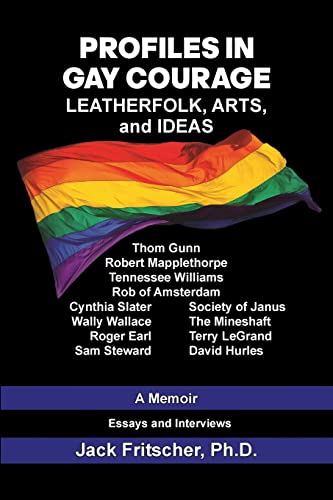

PROFILES IN GAY COURAGE

PROFILES IN GAY COURAGE

Leatherfolk, Arts, and Ideas

by Jack Fritscher, Ph.D.

Palm Drive Publishing

244 pages, $24.95

ANY NEW BOOK by Jack Fritscher is cause for celebration. In his stellar six-decade career, he has produced four novels, six shorter works of fiction, nine works of scholarly nonfiction, and innumerable pieces of erotic leathersex fiction. He was founding editor-in-chief of the legendary Drummer magazine. (Full disclosure: Fritscher published my first piece of fiction in Drummer in 1979, and we have corresponded since then.) To this reader, his Some Dance to Remember: A Memoir-Novel of San Francisco 1970-1982 is without peer, the definitive novel of gay life in 1970s San Francisco. His Mapplethorpe: Assault with a Deadly Camera is an insightful, passionate examination of Robert Mapplethorpe’s œuvre. As a novelist, short story writer, essayist, memoirist, pornographer, interviewer, filmmaker, and pop culture archeologist and archivist, Fritscher, along with his husband and artistic collaborator Mark Hemry, has not only reported on gay culture but has shaped it as well.

His latest work, Profiles in Gay Courage: Leatherfolk, Arts, and Ideas is a collection of essays celebrating “authentic leatherfolk founders, icons, and superstars too often under-reported by gatekeepers of gay-history timelines.”

“Robert Mapplethorpe: Fetishes, Faces, and Flowers of Evil,” the first essay in the book, begins with a paragraph that might serve as a raison d’être for much of Fritscher’s work: “The pre-AIDS past of the 1970s has become a strange country. We lived life differently those many years ago. The High Time was in full swing. Liberation was in the air, and so were we, performing nightly our high-wire sex acts in a circus without nets. If we fell, we fell with splendor in the grass. That carnival, ended now, has no more memory than the remembrance we give it, and we give remembrance here.”

“Robert Mapplethorpe: Fetishes, Faces, and Flowers of Evil,” the first essay in the book, begins with a paragraph that might serve as a raison d’être for much of Fritscher’s work: “The pre-AIDS past of the 1970s has become a strange country. We lived life differently those many years ago. The High Time was in full swing. Liberation was in the air, and so were we, performing nightly our high-wire sex acts in a circus without nets. If we fell, we fell with splendor in the grass. That carnival, ended now, has no more memory than the remembrance we give it, and we give remembrance here.”

Mapplethorpe entered Fritscher’s life in 1977 when he showed up at the Drummer office with a portfolio of photos. For an idea of how transgressive some of his photography is, look at “a self-portrait of the photographer as a young man, his crotch shot in close-up, with his two hands holding a Polaroid camera just above his flaccid penis to make the radical equation that his cock was his camera and his camera was a cock.” Mapplethorpe had simultaneously mounted two landmark solo shows, his Flowers and Portraits at the Holly Solomon Gallery, and his Erotic Pictures (which Solomon refused to show) at the Kitchen Gallery. That dichotomy between his “fine art” photos and his “obscene” photos continued through Mapplethorpe’s career, spurred by philistines who refused to recognize that his erotic photographs are fine art, culminating in a trial for obscenity in Cincinnati for his show The Perfect Moment at the Contemporary Arts Center. (The philistines lost.)

On March 9, 1989, Robert Mapplethorpe—“innocent as any victim,” Fritscher writes—died from AIDS-related complications at the pinnacle of his career. Fritscher’s remembrances of his artist lover are intimate, passionate, and clear-eyed. Future writing about Mapplethorpe by anyone else will be useless unless it draws upon Fritscher’s unique remembrances.

Writing about Samuel Steward, “the godfather of gay writing,” Fritscher tells us that Steward was born in 1909, into “the anti-gay century when owning one gay photograph meant jail.” Steward’s career included giving input to Dr. Alfred Kinsey at the Institute for Sex; chumming with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in their Paris salon; writing erotic S&M fiction under the pseudonym “Phil Andros” and nonfiction under his own name; becoming a popular university professor; tattooing some 150,000 men (primarily Hell’s Angels bikers and young sailors) as “Phil Sparrow”; and logging thousands of his sexual encounters (including ones with Rudolph Valentino and Rock Hudson). Fritscher’s affection and admiration for Steward are palpable.

Similarly affectionate portraits emerge in chapters on Tennessee Williams and Thom Gunn. The essay on Williams, “We All Live on Half of Something,” first appeared in Playbill: On Stage for the New York Art Theater Production of Something Cloudy, Something Clear in September 2001. The production was shut down by the horrors of 9/11 but came back on September 20th and closed on October 1st. Fritscher knew and interviewed Williams, whom he dubs “the most poetic of American dramatists and the most dramatic of American poets.” He asserts perceptively that “gorgeously doomed, Williams’ characters live as erotic castaways.” As for Williams’ legacy, Fritscher writes: “In Stella’s ‘Stanley,’ Williams and Brando launched a new postwar torn-T-shirt standard of masculine beauty. Their rough-trade blue-collar male sex appeal sold tickets and liberated pop culture’s gaze at men in the conformist 1950s.”

Fritscher’s essay on Thom Gunn is one of the longer and more personal in the book. These two titans of leather-dressed literature met in 1969. Reaching into Gunn’s collection Fighting Terms, My Sad Captains, My Cambridge, The Man With Night Sweats and others, as well as his memories of days and nights with Gunn, Fritscher constructs an intimate portrait of his dear friend, the Cambridge-educated British poet who emigrated from the U.K. to the U.S. and became a gay icon as well as an internationally celebrated poet. Fritscher is alert to every nuance in Gunn’s poetry and clear-eyed about his ultimately self-destructive drug use (Gunn died of an overdose in 2004). This is an exquisite, very moving essay.

I have devoured Jack Fritscher’s writing in all its forms since the 1970s, so I am well acquainted with his vast knowledge not only of the leather community but of pop culture in general, his muscular prose style, his engaging wit and humor, his fervid dedication to Leathermen and Leatherwomen around the world, and his commitment to preserving gay history. Even so, Profiles in Gay Courage astonished me with its depth of feeling and its perfect reconstruction of that glorious, heartbreaking time before, as Fritscher has put it, the free-sailing 1970s ran into the iceberg known as AIDS. The book made me sadly nostalgic for those days and nights of “libidinous joys only!” Profiles in Gay Courage is much, much more than a nostalgic recollection of those days. It will serve as an invaluable resource for anyone researching gay history in the 20th century.

Hank Trout has served as editor at a number of publications, most recently as senior editor for A&U: America’s AIDS Magazine.