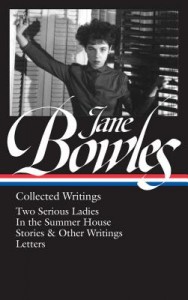

Jane Bowles: Collected Writings

Jane Bowles: Collected Writings

Edited by Millicent Dillon

Library of America. 815 pages, $40.

IN HIS MEMOIR Role Models (2010), John Waters singles out Jane Bowles as one of his favorite writers, and offers the following assessment of her only published novel, Two Serious Ladies: “Once I read it, I felt insanely grateful to have gone beyond the door of literate lunacy into a world of complete obliviousness to emotional reality. I’ve never come back. Two Serious Ladies made a real reader out of me, and if you give it a chance, it will do the same to you.”

That’s as good an introduction as any to the seemingly bewildering fiction of Bowles (1917–1973). The phrase, “if you give it a chance,” is telling—Bowles is a challenging writer, but as Waters and other champions of her work have attested—and these include Tennessee Williams, Truman Capote, and John Ashbery—she’s worth the effort. She’s not as well known as her husband, composer and writer Paul Bowles (1910–1999), most famous for his 1949 novel The Sheltering Sky, but this new Library of America edition of her work, magnificently edited by Bowles scholar Millicent Dillon, does justice to this unique and neglected writer.

Jane and Paul Bowles had one of the most unconventional relationships in American literature. When Jane first laid eyes on him at a party in New York City in 1937, she said to a friend, “He’s my enemy.” Yet they had many mutual literary and artistic friends, and after months of traveling together among this crowd, they developed a connection, and married in 1938. Theirs was an open relationship; Paul had affairs with both men and women, and Jane only with women. They traveled frequently and spent long periods apart, and they engaged in their many creative projects. Long-distance correspondence was one intimacy they maintained; Dillon includes many of Jane’s lengthy letters to Paul in the book’s letters section, which fills nearly 300 pages and spans more than thirty years.

Although their sexual connection was tenuous, Paul and Jane did collaborate creatively. He took a deep interest in Jane’s writing and offered extensive editorial suggestions on Two Serious Ladies, urging Jane to shorten the manuscript considerably. She took his advice (the excised chapters were later published as separate short stories, both included in this volume). As writers, Paul and Jane Bowles seem something like fraternal twins: they each have their own voice, but they share a strange world all their own. Robert Stone said Paul’s fiction carries “ruthless unsentimentality and cruel wit” in which the reader may experience “acutely the burrowing of paranoia’s worm, the comic yet distantly disturbing non sequitur, the hopelessly conplexifying suspicion.” Stone’s assessment could easily apply to Jane’s fiction, as well.

When Two Serious Ladies appeared in 1943, most critics didn’t know what to make of it. The women of the title are Christina Goering, a wealthy spinster obsessed with sin and salvation, and newlywed Frieda Copperfield, who seems less interested in her husband than in the young women she meets while vacationing with him in Panama. Both Christina and Frieda are restless, impulsive, and prone to seeking intimacy with random strangers. Indeed, their misadventures are nothing short of bizarre. Bowles’ prose is strangely electric, especially in the finely observed details of her place descriptions, as in an almost phantasmagoric interlude in which the Copperfields take an evening stroll down a street in a red light district. Two Serious Ladies fell out of print and into obscurity soon after it appeared. When a publisher contacted Jane to reissue it in 1965, she had to admit she didn’t even own a copy. But the book reappeared, and 22 years made a difference: critics were much more appreciative the second time around.

When Two Serious Ladies appeared in 1943, most critics didn’t know what to make of it. The women of the title are Christina Goering, a wealthy spinster obsessed with sin and salvation, and newlywed Frieda Copperfield, who seems less interested in her husband than in the young women she meets while vacationing with him in Panama. Both Christina and Frieda are restless, impulsive, and prone to seeking intimacy with random strangers. Indeed, their misadventures are nothing short of bizarre. Bowles’ prose is strangely electric, especially in the finely observed details of her place descriptions, as in an almost phantasmagoric interlude in which the Copperfields take an evening stroll down a street in a red light district. Two Serious Ladies fell out of print and into obscurity soon after it appeared. When a publisher contacted Jane to reissue it in 1965, she had to admit she didn’t even own a copy. But the book reappeared, and 22 years made a difference: critics were much more appreciative the second time around.

In 1966, Plain Pleasures, a collection of Jane’s short stories, was published in England. These stories are included in the Library of America volume. “A Guatemalan Idyll” and “A Day in the Open” were originally part of Two Serious Ladies. Attentive readers will recognize characters from the novel, but each story stands well enough on its own. In “A Stick of Green Candy,” Bowles takes her readers into the vividly imagined interior world of a young girl who fantasizes that she’s in command of an army of men. “Camp Cataract” is an arresting tale about the troubled relationship between two sisters, peopled by memorably strange secondary characters. It ends on a surreal and shocking note.

Jane Bowles’ fiction is full of surprises. In its themes and in its language, one continually encounters the unexpected, the off-kilter, and the jarring. She seems to be exploring such existential questions as, “What is it to be a person?” and “How can each person manage the perplexity of existence and ever hope to connect with another?” In this way, much of Paul’s fiction serves as a good companion to Jane’s. One thinks, in particular, of the disturbingly suggested father-son incest, and the broader themes of alienation, in his dark short story “Pages from Cold Point.” (The Library of America published a two-volume collection of Paul Bowles’ fiction in 2002.)

In addition to Two Serious Ladies, the short fiction, and the letters, the Library of America volume also includes Jane’s play In the Summer House, as well as a number of scenes and fragments, and an appendix with the story “Everything Is Nice” that Paul reworked from an unfinished piece and later published under Jane’s name. Detailed text notes and an extensive chronology provide further background on Jane’s life and work. All told, Millicent Dillon has produced an indispensable edition of Jane Bowles’ work.

Jim Nawrocki is a writer based in San Francisco.

Discussion1 Comment

Thank you, Jim. Thank you very much. Any info about the enigmatic, perverse Jane Bowles is welcome. Her reputation largely rests on a few complimentary comments by a few prominent homosexuals: Capote, Tennessee Williams, Vidal (Gore not Sassoon), and, of course, John Ashberry. Without these comments, my guess is that Jane would be almost completely forgotten today. There are many a quirky novel or two or twenty that never had any famous authors read them, let alone praise them. Mrs. Bowles, who probably never consummated her marriage to Paul, benefited greatly by being known to these great men through socializing more than through her writing. My key question: If Jane had not been associated with Paul, would her work be considered in such high esteem that it would merit inclusion in the once-august Library of America’s canon? The answer is an almost certain “No!”.

Again, thank you for your review of this collection of writings of this forgotten genius.