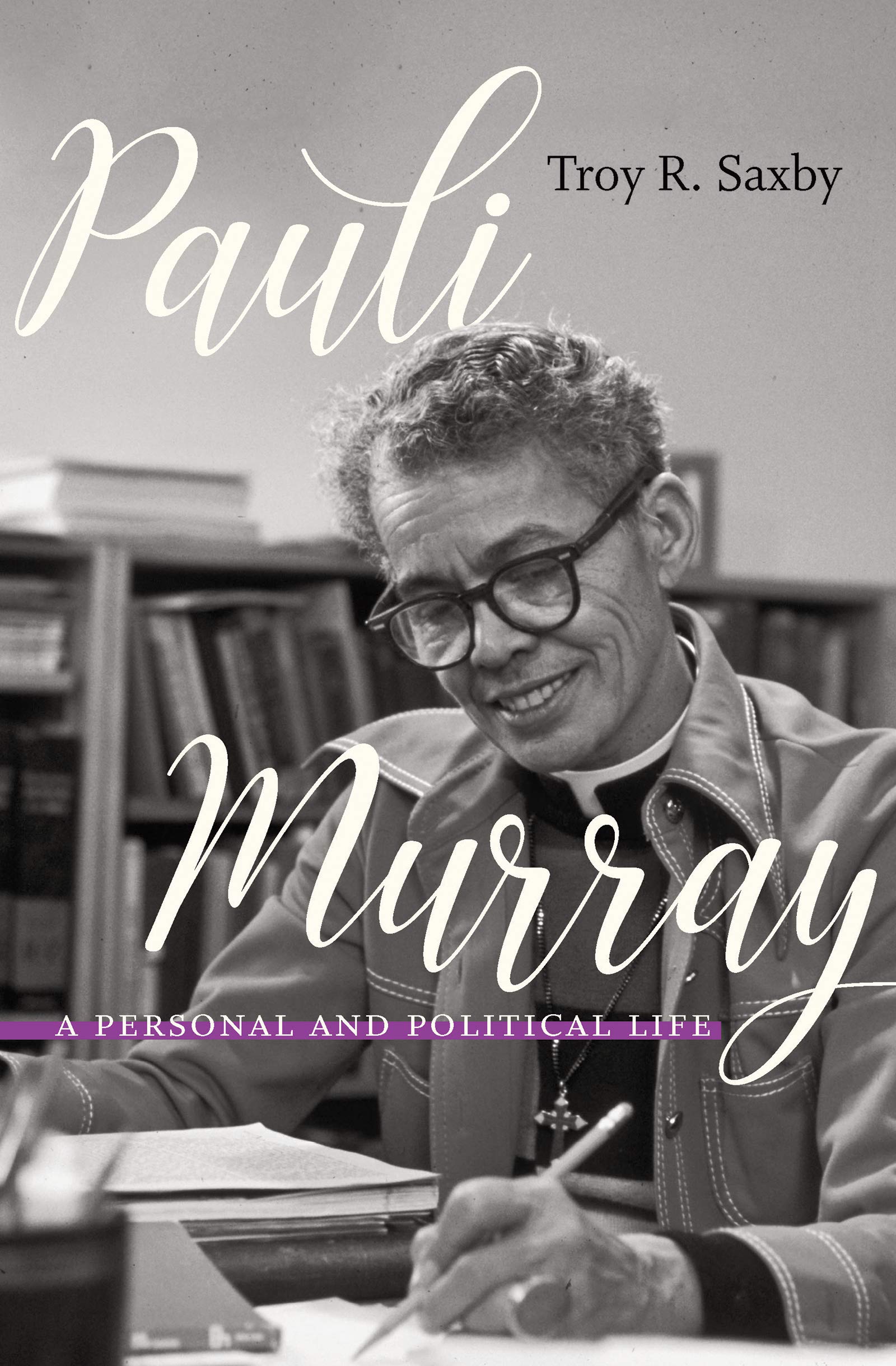

PAULI MURRAY

PAULI MURRAY

A Personal and Political Life

by Troy R. Saxby

University of North Carolina Press

353 pages, $34.95

THE RECENT SUNDANCE premier of Betsy West and Julie Cohen’s documentary My Name Is Pauli Murray has returned this groundbreaking figure to the public eye. Although Murray is already the subject of two respected biographies, academic Troy R. Saxby has undertaken a third, a volume that purports to highlight the interplay between the activist’s personal life and her considerable cultural achievements.

Let me state at the outset that I use the female pronoun advisedly in recognition of the fact that in early life Murray regarded herself as a man trapped in a woman’s body. Had she lived today, she may have opted for another pronoun—and transgender activists may rightly claim Murray as a forebear—but in the interest of historical authenticity I have elected to use the only pronoun available to Murray during her lifetime. This consideration points to one of the many complexities facing a biographer hoping to shed light on this subject’s private life. That Saxby fails to ponder pronoun use suggests greater failings in his discussion of sexual orientation and gender identity.

To its credit, this biography spotlights an often overlooked feminist scholar and legal activist. Arising from humble beginnings in North Carolina, Murray fought racism, gender bias, and unspoken but palpable homophobia to become the first African-American individual to get a Yale Law doctorate and the first African-American woman to become an Episcopal priest. Murray blazed trails well in advance of more celebrated civil rights actions. She tried to integrate Southern schools long before Little Rock, organized “stool sitting” protests at segregated restaurants seventeen years before the Greensboro lunch counter sit-ins, and helped plan a Journey of Reconciliation to Southern states thirteen years before the Freedom Rides. As a legal scholar and activist, Murray was credited by Ruth Bader Ginsberg as the thinker who first applied the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause to women, a concept that redefined women’s legal status and laid the foundation for important decisions promoting women’s rights.

That Murray practiced deliberate obfuscation about her relationships with women during her lifetime is not in doubt. Thus interrogation into her sexual orientation and gender identity presents a challenge to a biographer aiming to explore Murray’s private life. Still, even allowing for this difficulty, Saxby falls short. Let’s start with his persistent use of the expression “sexual preference” when discussing Murray’s same-sex attractions and affairs. His use of this outdated term points to a lack of awareness of its distasteful implications for people inside and outside the LGBT community. Another difficulty is his tendency to over-speculate from too little concrete evidence. Conjectures about what Murray “must have felt,” that an event “may have reminded Murray” of something, or that childhood fears “must have been awakened” work to undermine Saxby’s narrative authority.

That Murray practiced deliberate obfuscation about her relationships with women during her lifetime is not in doubt. Thus interrogation into her sexual orientation and gender identity presents a challenge to a biographer aiming to explore Murray’s private life. Still, even allowing for this difficulty, Saxby falls short. Let’s start with his persistent use of the expression “sexual preference” when discussing Murray’s same-sex attractions and affairs. His use of this outdated term points to a lack of awareness of its distasteful implications for people inside and outside the LGBT community. Another difficulty is his tendency to over-speculate from too little concrete evidence. Conjectures about what Murray “must have felt,” that an event “may have reminded Murray” of something, or that childhood fears “must have been awakened” work to undermine Saxby’s narrative authority.

In addition, the book could have benefited from a firmer structure to organize a life of outstanding accomplishment but also considerable complexity. The events of Murray’s life make for compelling reading, but Saxby offers so much detail that a reader risks getting bogged down in minutia. Needed is more evaluation and synthesis of all this information. Without that, Saxby’s objective “to provide a sense of what life was like for this remarkable individual” remains only partially fulfilled. Still, one can hope that future biographers will build on Saxby’s exploration of the human side of Pauli Murray, so that she can take her place in the pantheon of LGBT thinkers and activists.

Anne Charles is a retired teacher and writer living in Vermont.