Editors Note: Our last issue included a feature-length review of an exhibit at the Met in New York titled Camp: Notes on Fashion. While author Cassandra Langer took a somewhat dim view of the collection, Chris Freeman was inspired to write this piece.

ON THE STAND at the Old Bailey in April 1895, Oscar Wilde admitted: “At times one says things flippantly when one should speak more seriously.”* Wilde made a career of camping—on stage and on the page. However, in the courtroom, that most dangerous stage, his witticisms, which were an attempt to subvert and deflate the legal predicament he found himself in, not only fell flat but got him two years of hard labor.

With that in mind, I want to explore the limits of camp—instances in which the uses of camp and its discursive power, if one can speak of camp in such terms, hit a wall, when camp collides with what we might call “anti-camp.” What happens then? Is there a point at which camp has to shut up, or shut down? Scholar and critic Allan Pero has asserted that “Camp is not a supplement, but a needful weapon in a handbag of dangerous accessories.” But it seems to me that this particular accessory must be deployed carefully and under particular circumstances. Perhaps it should carry a warning label: Not effective against certain enemies.

Wilde foolishly prosecuted the Marquess of Queensberry, father of Lord Alfred Douglas, for libel, as Queensberry had accused Wilde of “posing as a somdomite [sic].” At the trial, Wilde was cross-examined by Edward Carson for two-and-a-half days, relentlessly. Wilde’s literary works, especially the 1890 Lippincott’s edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray, were used against him. (Wilde’s friends were scandalized by that edition of the novel; in a rare moment of discretion, Wilde cut many of the most suggestive passages for the 1891 edition).

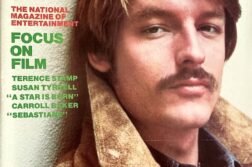

Robana via Getty Images.

At the cross-examination, on the morning of Wednesday, April 3rd, Wilde began by lying about his age. Since he had gone to university with Carson, that was a bad idea. It went downhill from there.

All afternoon he was asked about numerous young male friends: Taylor, Wood, Shelley, Conway, and others, with questions like, “How old was he?”, “Did you ever give him money?”, and “Did you ever open his trousers?” (Trial, 194-213). Thursday morning, things went from bad to worse. When asked about hosting young Charles Parker for tea, Wilde replied: “I delight in the society of people much younger than myself. I like those who may be called idle and careless. I recognize no social distinctions at all of any kind, and to me youth—the mere fact of youth—is so wonderful that I would sooner talk to a young man half an hour than even be, well, cross-examined in court” (Trial, 175). The gallery laughed; the judge and jury did not. Questioning about Parker takes up more than ten pages of the transcript; Wilde’s side of the dialogue reads more like a man being interviewed for a puff piece than a court proceeding.

And then, the nadir: Wilde was asked about his relationship with Walter Grainger, who was sixteen years old. “Did you ever kiss him?” “Oh no, never in my life. He was a peculiarly plain boy.” Carson, like a dog with a bone, spent several minutes, which must have felt like hours, pressing the issue of ugliness. Trapped, Wilde finally said: “The questions are grotesque … you sting me, insult me and try to unnerve me in every way. At times one says things flippantly when one should speak more seriously. I admit that, I admit it—I cannot help it. That is what you are doing to me” (Trial, 200-09). These words, which have become iconic and heroic in queer history and pop culture, were damning at the

time. And, of course, Wilde had done it to himself.

Wilde’s last sustained prose work, a sort of tortured love letter to Lord Alfred Douglas (Bosie), was published as De Profundis. Notoriously and unapologetically, Wilde wrote: “People thought it dreadful of me to have entertained at dinner the evil things of life, and to have found pleasure in their company. But they, from the point of view through which I, as an artist, approached them, were delightfully suggestive and entertaining. It was like feasting with panthers. The danger was half the excitement. I used to feel like a snake-charmer must feel when he lures the cobra to stir from a painted cloth or reed-basket that holds it, and makes it spread its hood at his bidding, to sway to and fro in the air. … They were to me the brightest of gilded snakes.” Wait, is he still talking about snakes? Here is his confession, in which he camps it up again, this time for posterity, not for the law. Perhaps in the depths of his Profundis, Wilde gets another, if not the last, laugh.

So, how does camp hold up against force? Resistance is resistance, I grant you. But sometimes, camp is the wrong choice; it is impossible. Or it is deadly. So, camp with care.

* Merlin Holland, The Real Trial of Oscar Wilde(Fourth Estate/HarperCollins, 2003), 209. While there are many versions of Wilde’s trials, some of dubious reliability, Holland’s recent volume is arguable the most credible account. Hereafter, abbreviated in the text as Trial.

Chris Freeman teaches at the University of Southern California. He is co-editor of the forthcomingIsherwood in Transit (University of Minnesota Press, 2020).