CHLOE SHERMAN’S Renegades: San Francisco: The 1990s (published by Hatje Cantz) captures the city’s lesbian and queer life in sexy, buoyantly expressive photos. The heavily saturated colors in many of the pictures give birthday parties and bar meetups a mesmerizing glamor, and the young women in the photos, mostly friends of Sherman’s, exude self-confidence in themselves and trust in their chronicler. That sense of trust and connection strikes me as one of the book’s most distinctive qualities, and it is one that Sherman herself greatly values.

I caught up with Sherman recently to learn more about her and the lesbian and queer subculture in and around San Francisco’s Mission District when it was still possible to move there on a youthful whim and, by closing time at the Bearded Lady, have a decent place to live and at least one friend to sleep with. This interview was conducted by email in late December 2023.

Hilary Holladay: Since the theme of this issue is “San Francisco,” let’s start with a question about the city. You moved to San Francisco when you were 21 at the beginning of the 1990s, which is the decade that you chronicle in Renegades. What did you do before you enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute and earned your BFA in photography?

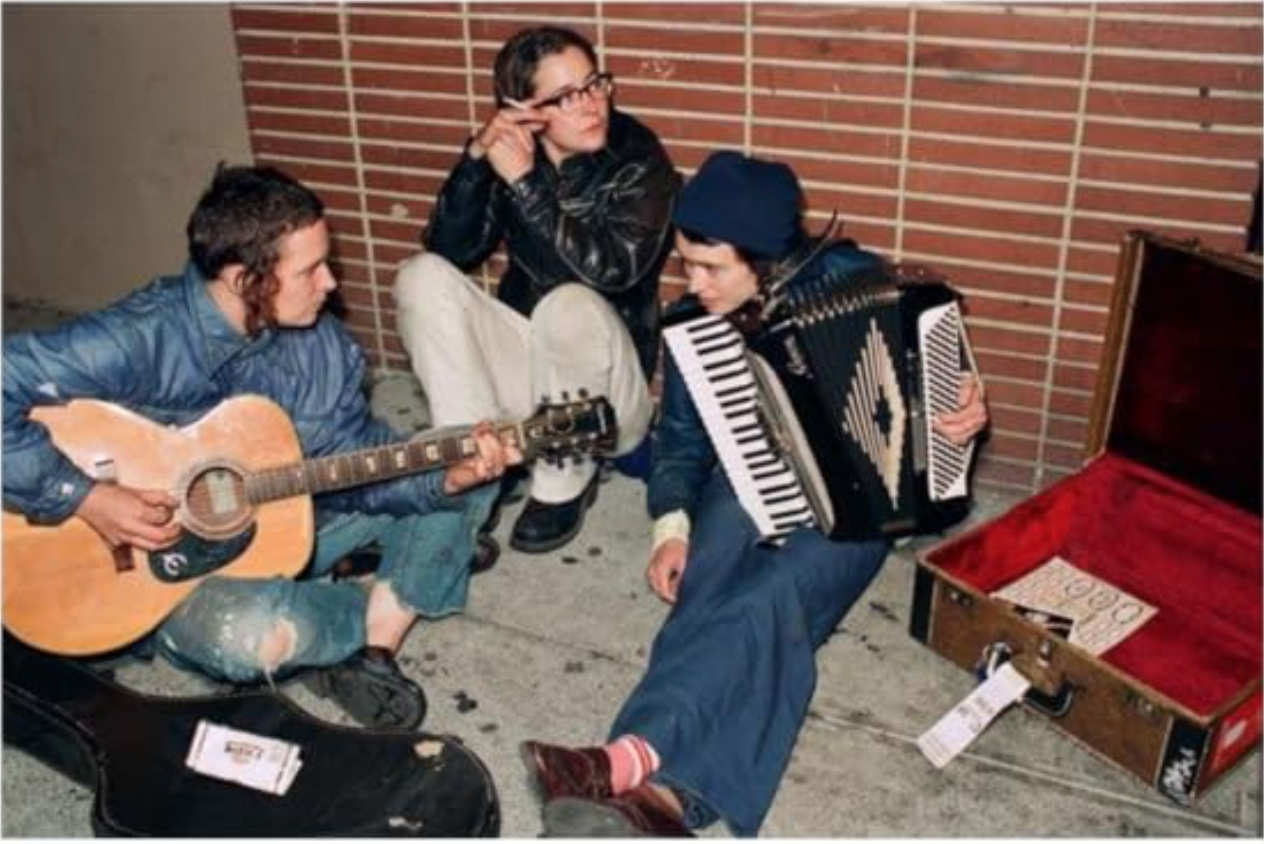

Chloe Sherman: I was a bike messenger for a bit; I worked in produce at a health food store; I worked some at the Bearded Lady Cafe. I traveled when opportunities arose. I went on a European and a U.S. tour with the band Tribe 8 in my earlier years. There were so many bands at the time—most of my friends were in a band at some point. I started a band with six other people in the mid-’90s called Cypher in the Snow. I played bass, and we recorded a few albums and also toured the U.S. and had a few West Coast tours. There was a “queercore”/“homocore” music movement. There really was room in San Francisco to collaborate and make things come to fruition.

CS: It was a bustling, dynamic, and creative time. Queer youth, outcasts, and artists flocked to the city to find one another. People were experimental with art, with self-expression, with style, with gender. And the city was vibrant. A queer cultural renaissance was unfolding while people showed up, joined forces, made new rules, and lived free.

The Mission District and surrounding neighborhoods became a hub of queer-centric businesses, clubs, bars, cafés, tattoo shops, bookstores, galleries, and performance spaces. There was a growing and strong sense of community and collaboration, a sense of collective creativity, of support, of pride and a strident defiance of cultural norms.

HH: What was it like at the San Francisco Art Institute when you were a student there?

CS: I loved my time at SFAI. It was a special place with an impressive history of educating renowned artists like Annie Leibovitz, Cathy Opie, and Dorothea Lange, and the building hosts a spectacular Diego Rivera mural. It was an inspiring and productive place to be—a creative incubator. I was immersed in photography and friends with painters and multimedia artists, all of us talking about our work and brimming with ideas. I had great mentors and professors. My photographic subject was self-guided, but my work was welcomed and well-reviewed.

HH: Where did you live in those days, and how has San Francisco changed in recent decades?

CS: I lived in the Mission when I first moved to San Francisco, first on 14th St., then on 22nd St. I was briefly in the Lower Haight on Pierce Street near Duboce Park, then I settled for years in Noe Valley off 24th St. It was easy to move into a room in a flat with people you knew.

One of the biggest changes today has been the price increase in rents and housing. Many people were forced out of the city beginning in the early 2000s, and they dispersed around the Bay Area and across the country. Many of the businesses that opened in the ’90s have since shut down, as people have moved away.

San Francisco is still amazing but very different than it was thirty years ago. It was a gay mecca then and still is, but it’s far less gritty and artistic today, since many artists have been forced out due to expensive housing. I do find it sad to witness people being priced out. Working artists and musicians and financially less established communities have been leaving for a while now. Their absence leaves a void, a cultural void.

HH: What were some of the landmark lesbian and gay businesses in the ’90s?

CS: There were just so many queer businesses at the time. The Bearded Lady Cafe and the Lexington Club are both in my book, but there was also Black and Blue Tattoo, Dog-Eared Books, Leather Tongue Video, Club Junk—the list is expansive. Black and Blue Tattoo still exists, in a different location. Today, I feel there is a surge of cool, interesting Mission District queer DIY businesses.

HH: Do you still live in San Francisco?

CS: I still live in the San Francisco Bay Area—I never left. I work in San Francisco, my photo lab is there. I love connecting and reminiscing with “old-timers” who remained in the city and the Bay Area. The city has changed, as do all cities and communities over time. However, we welcome moving forward, while we fondly reminisce. It’s been exciting to witness a recent surge of new spaces such as Mother Bar, at 16th and Valencia streets, opened this year by Malia Spanyol. It’s a ’90s-esque, fun, æsthetically beautiful, hip, welcoming queer bar.

HH: I’m also curious about your pre-San Francisco years. Where did you grow up?

CS: I was born in Manhattan, where my mother grew up. Eventually, we moved to my father’s hometown of Chicago, where my extended Sherman family still resides. My parents were fond of the great outdoors, and we later moved to Portland, Oregon. Over the years, I continued to spend time in New York City and Chicago, visiting grandparents and other close family.

HH: How and when did you get started as a photographer?

CS: I was always a sentimentalist, and this pairs well with photography. My love for photography began early—looking through family albums at my father’s images. He’s an excellent photographer. I watched him shoot, viewed his photographs, and enjoyed using his 35mm film cameras. I took formal photography and darkroom classes in high school. My parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles, all had art on the walls, and we had photography books in the house. I remember being enamored of a book of photos by Dorothea Lange, and also a Bruce Davidson book. My first photos were still lifes and nature.

HH: How did you get started taking photos of people, and LGBT people in particular?

CS: As I grew comfortable taking pictures, photographing people became an obvious focus. I’m drawn to people, interactions, poignant moments. I have engaged with my work, stories, and subjects as a documentary photographer, hoping to tell a story with photographs. My style and approach have remained similar over the years. I continue to be drawn to subcultures, stories, people. I travel frequently, so I take pictures of new spaces and appreciate new environments. I began photographing my surroundings in San Francisco upon arriving. So, I suppose moving to San Francisco sparked the beginning of this “San Francisco story.”

HH: When did you get the idea to make a book out of your San Francisco photos?

CS: As I began to review, unpack, and rediscover many of these images, their narrative content and historical aspect seemed appropriate for a book. I was offered a solo show in Berlin at F3 Gallery, and incidentally, a book deal—if we could compile and publish in time for the opening of the exhibit.

HH: Could you tell me the back story for Anna Joy Post-Surgery at Home?

CS: That was just another afternoon visiting Anna Joy Springer at her house. We are close friends, and I was visiting her after a surgery and taking photos as usual. I spent lots of time at her place. I’m sure I was struck by her red satin robe and the recovery ephemera surrounding her, and the huge wooden green ashtray she brought back from a trip to Bali.

HH: On the Way to Folsom St. Fair, 1994 is intriguing. This group portrait has an intense lesbian vibe, with all the women making eye contact with you. What’s the story here?

CS: This photo is very early; it was black-and-white film and before I actively chose to switch to color. The location was Red Dora’s Bearded Lady Café, a go-to gathering spot and meeting place. Before cellphones and the digital age, we basically showed up at the Bearded Lady before every event, and to plan for the day or night: wake up, exit flat, stumble to the Bearded Lady to get coffee, breakfast, and hang out on the patio waiting for the place to fill up with friends and acquaintances. This photo was a gathering for coffee around the front counter, with women ordering and talking with whoever was working there before making their way to the Folsom Street events. People were confidant and flamboyant and happy to be photographed.

HH: I was struck by Daniel Sea, Mid-90s. What’s the story behind this photo of the actor who played the trans character Max in The L Word?

CS: Daniel was not in The L Word yet. We were in a band together, Cypher in the Snow, with Anna Joy Springer and five other musicians and friends. We spent a lot of time together for gigs and on tour. This shot was just a casual moment out with people, not from a notable event.

HH: How is it different doing documentary photography of friends versus strangers?

CS: I often become familiar with and even close to the people I’m photographing. Documentary photography chronicles people in their communities, in both their public and private spaces. It requires building trust to be allowed access to people’s lives, to quiet moments. Photographing my San Francisco community, I already had access, trust, and familiarity. I was already on the inside. This inside access allowed the extensive time span, as these photos span a whole decade.

HH: Renegades includes some great photos of very fashion-conscious, butch lesbians. In your observation, has butch culture largely faded away? If so, do you have thoughts on why that is?

CS: I would say the access to medical care to transition from one’s birth gender is more present now than it was twenty or thirty years ago. It is true that now many of the butches in my photos have since transitioned from their birth gender. In this way, butch culture has shifted. However, it certainly has not disappeared.

HH: If you were going to do an edition of Renegades set in the 2020s, where would you go to take the pictures for it?

CS: I think there are many major cities where you can find a strong community that has hints of what I present in Renegades: London, Berlin, Chicago, New York, LA. I’ve been amazed at the diversity and strength of queer communities today.

HH: What projects are you currently working on?

CS: I would love to do a “book two” with this work in some capacity. I’m working on a project that holds promise to be a book—we’ll see. And my solo show Renegades will continue to tour through Europe.

Hilary Holladay, a frequent contributor to these pages, is the author of The Power of Adrienne Rich: A Biography.