WHEN PAUL CADMUS died in 1999, days before his 95th birthday, there was barely a ripple in the art world. It’s hard to recall that 65 years earlier he had been the enfant terrible of the art world when his painting of frolicking sailors, The Fleet’s In!, caused an epic scandal. This is the story of Cadmus’ meteoric rise and subsequent erasure, which has complicated his place in art history and obscured his work for younger generations.

Throughout his life, Cadmus rejected the label of “gay artist,” asking that we focus on the quality of his work as art. Nevertheless, his art was inextricably linked to his life and thus includes references to his male lovers, his love triangles, and the gay places that he frequented, such as Fire Island beaches, the New York City docks, and the YMCA.

A son of artists who encouraged his early artistic inclinations (as well as those of his sister Fidelma), Cadmus was an extraordinary painter who became infamous for his gritty, sexually charged scenes, which pushed the envelope of acceptability to the breaking point. While studying at New York’s Art Students League, he met the remarkable fellow artist Jared French (1905–88), who became his lover and the most important influence on his work. It was French who encouraged him to abandon commercial work to become a fine artist.

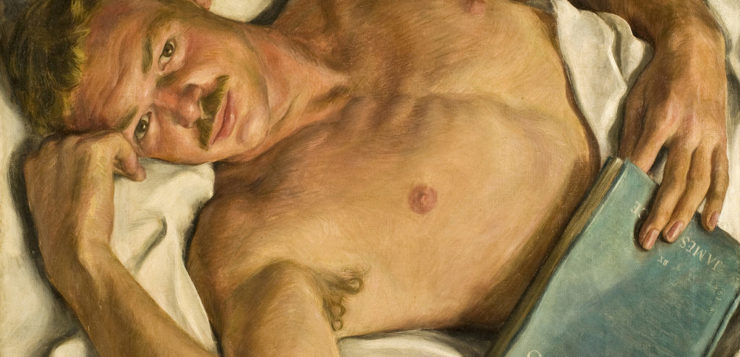

Like most American painters at this time, French and Cadmus traveled to Europe to absorb its culture and gain recognition for their work. Soon after they arrived, Cadmus painted his first mature painting, titled Jerry (1931), which was a portrait of French. In this daring work, Cadmus’ lover engages our gaze, bare-chested on tousled sheets that suggest a recent sexual encounter. With this visual manifesto, Cadmus alchemized their bond as artists. French is holding a copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses, which was banned in the U.S. for obscenity and thus symbolized their quest for freedom of expression.

Cadmus had written that “many Renaissance artists were queer before the emergence of queer identity,” a sentiment that was confirmed when they visited Luca Signorelli’s frescoes (1504) for the Orvieto cathedral in Italy. The revolutionary, openly homoerotic murals, a key influence for Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, left an indelible imprint on Cadmus that stayed with him for the rest of his career.

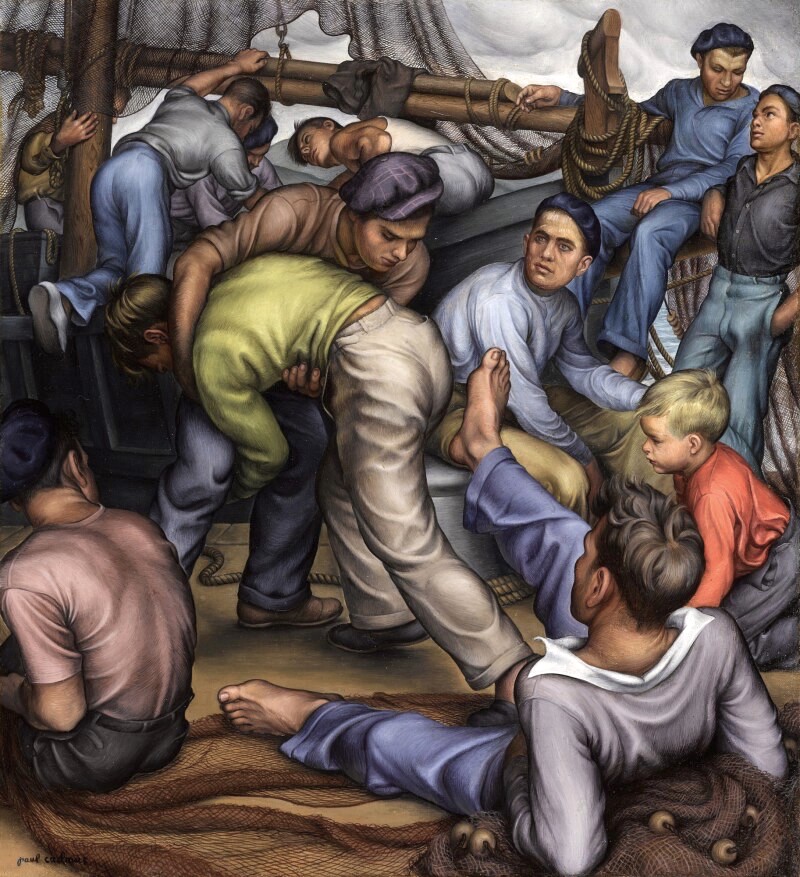

The two artists settled on the Spanish island of Mallorca where, perhaps out of nostalgia, Cadmus created unequivocally American scenes that combined a Renaissance-inflected style with contemporary satire and brazenly gay subjects. Risking artistic suicide, these landmark works reintroduced the homoerotic beauty of the male body in art after centuries of forced exile.fjerrt YMCA Locker Room (1933) depicts an older man propositioning a young hunk whose scanties barely conceal his private parts. Shore Leave (1933) features a menagerie of sailors who interact with sexually ambiguous female figures while a gay pickup takes place in the background. A beefy sailor with bulging buttocks in skintight pants echoes the sexually charged male figures in Signorelli’s frescoes.

In Greenwich Village Cafeteria (1934), a man with painted nails seduces the viewer into joining him in the restroom. In Gilding the Acrobats (1935), a circus theme cloaks its nakedness and a clear suggestion of fellatio, which is what Cadmus was interested in. This is when scandal began to raise its ugly head. When the Whitney Museum unveiled the satirical Coney Island (1935), featuring a young man mesmerized by a bodybuilder and a world of uncouth behavior, a Coney Island trade group threatened a civil suit. A few years later, Sailors and Floozies (1939), in which a male-looking woman admires a gorgeous sailor posing as an Odalisque, caused a national scandal. The painting was removed and later remounted at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Exhibition.

§

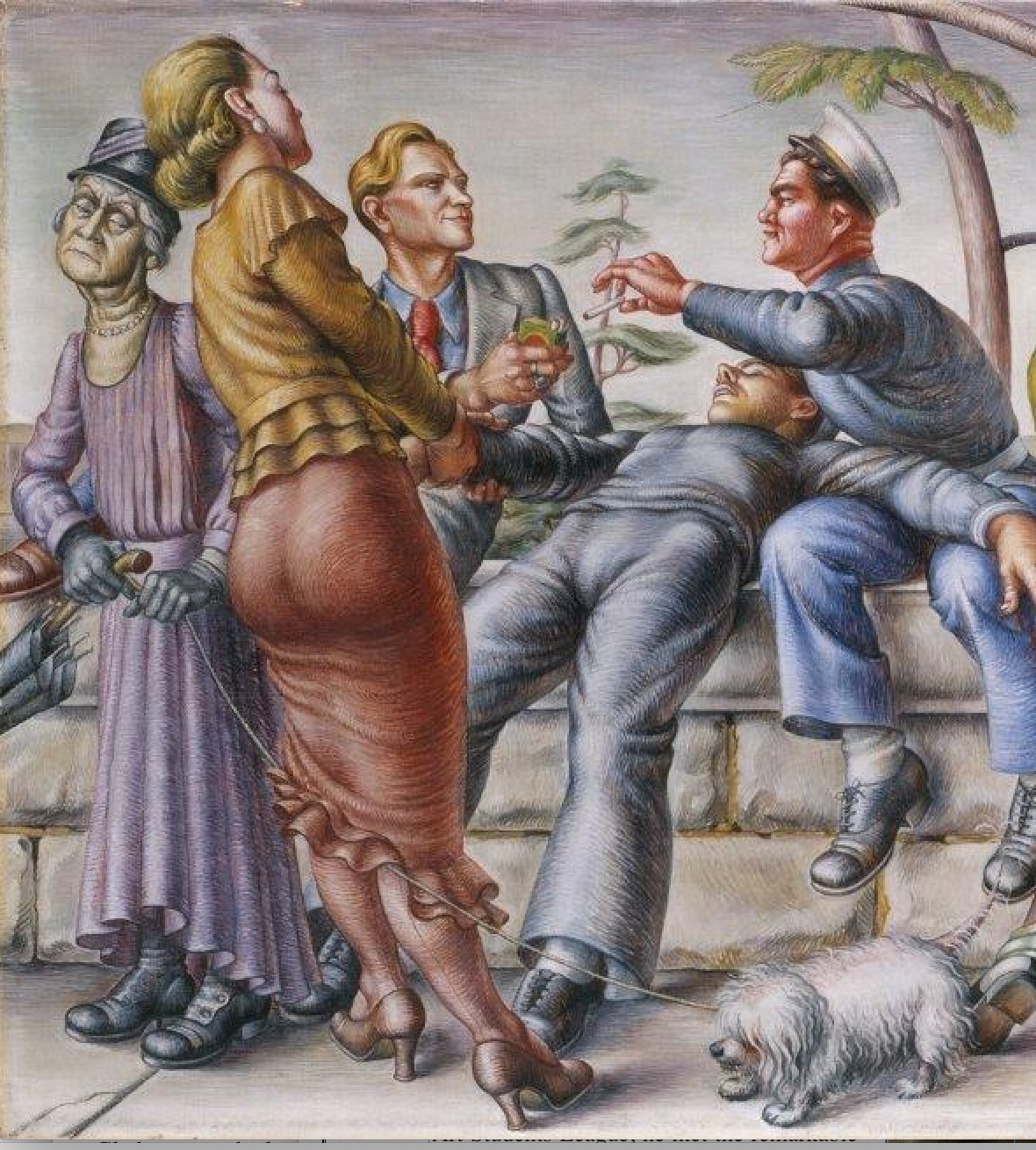

Just when their money and their passports were running out, Cadmus received a letter from his sister telling him about a government-sponsored New Deal program called Public Works of Art Project. They returned to the U.S. immediately, where Cadmus became one of the project’s first participants. Instead of creating a typical American scene, Cadmus submitted The Fleet’s In! (1934), a wild scene of drunken sailors interacting with civilians and sketchy women inspired by his memories of the uninhibited sailors who flooded New York’s Riverside Park.

A retired U.S. Navy admiral, upon spotting a reproduction of The Fleet’s In! before its opening at Washington’s Corcoran Gallery, published a letter in multiple newspapers that accused the painting of depicting “a most disgraceful, sordid, disreputable, drunken brawl.” The admiral ordered the assistant secretary of the Navy, who was President Roosevelt’s cousin, to remove it from the show to ensure that it would never be seen again. The Navy had no authority over the Corcoran, but because of the secretary’s connection to Roosevelt, no one stopped him when he lifted the painting from the wall and took it home. The painting eventually landed at the Alibi Club, an all-male lounge for high-ranking officials, where it hung for decades.

Outraged that a government official had censored a government-funded work of art, Cadmus furnished newspapers across the country with quotations and photographs related to the painting and the attempt to suppress it. The ensuing scandal catapulted Cadmus to front-page news and national notoriety. In the aptly titled documentary Paul Cadmus: Enfant Terrible at 80, Cadmus noted with relish: “I owe the start of my career to the Admiral who tried to suppress it.”

Indeed the most striking thing about the Fleets In! scandal is that no one mentioned the homosexual subtext of the painting. They denounced the loose women and drunken sailors, but once you delve into this scene of general debauchery, you notice at its center an unmistakable gay pickup in progress. We see a well-groomed man wearing a red tie offering a cigarette to a Marine, who eagerly accepts it. As George Chauncey wrote in Gay New York: “The blond civilian with plucked eyebrows, rouged lips and powdered face is the 30s archetype of the gay ‘fairy.’ His red tie was a well-known queer code that conveyed his availability.” The painting’s queerness extends beyond this encounter. At the far right, we’re presented with the suggestive buttocks of two sailors in close proximity. The female figure in the red dress is not without a hint of gender ambiguity, including a prominent Adam’s apple.

In a historic sleight of hand, Cadmus had used satire as his pretext for depicting the cruising rituals of the gay community. During the brouhaha over the painting, Cadmus received death threats that forced him to stay with relatives until the scandal subsided. It wasn’t until a 1981 retrospective that he was reunited with the painting, which he hadn’t seen in 47 years. In the intervening years, he had the pleasure of seeing how his painting had inspired Jerome Robbins’ ballet Fancy Free, which became the source for the Broadway musical On the Town (1944).

Notwithstanding the Fleet’s In! scandal, the government commissioned Cadmus to paint a large mural for a Virginia Post building. When Pocahontas and Captain John Smith was unveiled in 1938, officials objected to the phallic loincloth worn by one of the Indians. Cadmus gladly retouched that part of the painting, gleefully relieved that no one had expressed concern over a warrior’s prominently placed male buttocks.

Benefiting from the publicity, Cadmus had his first solo gallery show. More than 7,000 visitors came through, eager to see what all the fuss was about. But just as he was enjoying the sweet smell of success, Jared French, who was still his lover, married a mutual friend, photographer Margaret Hoening (1906–1998). She allowed her husband to continue seeing Cadmus in what became the first of several triangular relationships in the latter’s life.

In Cadmus’ painting The Shower (1943), one of the first examples of his “magic realism” style, Margaret looks peacefully at her husband, as French and Cadmus, both naked, are connected by the flow of white, semen-like water. The indomitable trio shared summer vacations on Fire Island, where they took carefully posed black-and-white photographs of each other, many in the nude, done in a Surrealist style. In jest, they called themselves PaJaMa, taking the first two letters from each of their first names. The photos, which flaunted their alternative sexual lives, also documented the burgeoning gay culture on Fire Island. (They also went to Provincetown.) They gave these images to their friends and lovers as gifts until they started to appear in galleries, where they were now fetching thousands of dollars.

A frequent visitor and willing participant in these photo outings was the dashing artist George Tooker (1920–2011), who became the vertex in another love triangle. Cadmus supposedly boasted that “I had Jerry in the daytime and George at night.” Tooker declared that, while French and Cadmus were crucial for his finding his own artistic style, Tooker had to break up with Cadmus, who always forced French into the equation, while Tooker wanted exclusivity.

As this drama unfolded, Lincoln Kirstein (1907–1996), the influential arts patron at the epicenter of New York’s network of queer artists, entered their lives. Kirstein, who had cofounded the New York City Ballet, was instantly smitten with Cadmus’ impeccable manners, perfect face, and striking blue eyes. The fact that Kirstein’s infatuation was apparently unrequited didn’t diminish his patronage of Cadmus. Aware that the artist’s work wasn’t commercially viable because of its daring subject matter, Kirstein acquired many pieces and commissioned others, such as a scandalous see-through costume for a hunky dancer in the 1937 ballet Filling Station. In a stunning move calculated to allow him to stay close to Cadmus, Kirstein married the latter’s sister Fidelma in 1941, soon after they met. Their marriage lasted until her death fifty years later, but Kirstein continued to have sex openly with men all his life.

This is the period in which Cadmus’ near erasure in the art world began. Despite his success, art critics ignored him starting in the 1940s and continuing until gay studies resuscitated his work in the 1980s. A key reason is that American art shifted during the postwar years away from representation and toward Abstract Expressionism. Artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko eclipsed Cadmus’ works of magical realism, which were even accused of being un-American.

Nevertheless, this dismissal by the cognoscenti did not clip Cadmus’ artistic wings. Instead, he thrived, creating works that exposed the sexual hypocrisy of his time with hiding-in-plain-sight queer images that continued to provoke the conservative public. Remarked Cadmus: “I like to exaggerate, rub people’s noses [in it]so they notice.” The obsession with sailors resumed with Fantasia on a Theme by Dr. S. (1946), where a semi-nude sailor is the focus of all the attention, including a group of phallic lights around his head.

§

Cadmus’ time in Europe in the early 1950s greatly influenced his subsequent work. In Finistere (1952), he directs our attention to the insertion of a suggestive bicycle seat into the derriere of a young man who’s holding a huge loaf of bread while he looks at a potential male partner pulling his tight swimsuit down. In Bar Italia (1955) he depicts the American tourist invasion of postwar Italy in a boisterous scene into which he inserts a self-portrait gawking at the crotch of a burly local man as well as a group of gay men who could be talking about someone’s penis size. In The Bath (1951), two nude men unabashedly share a bathroom as they carry out their ablutions. This scene of gay domesticity, probably the first in modern Western art, anticipated David Hockney’s scenes of gay life by more than a decade.

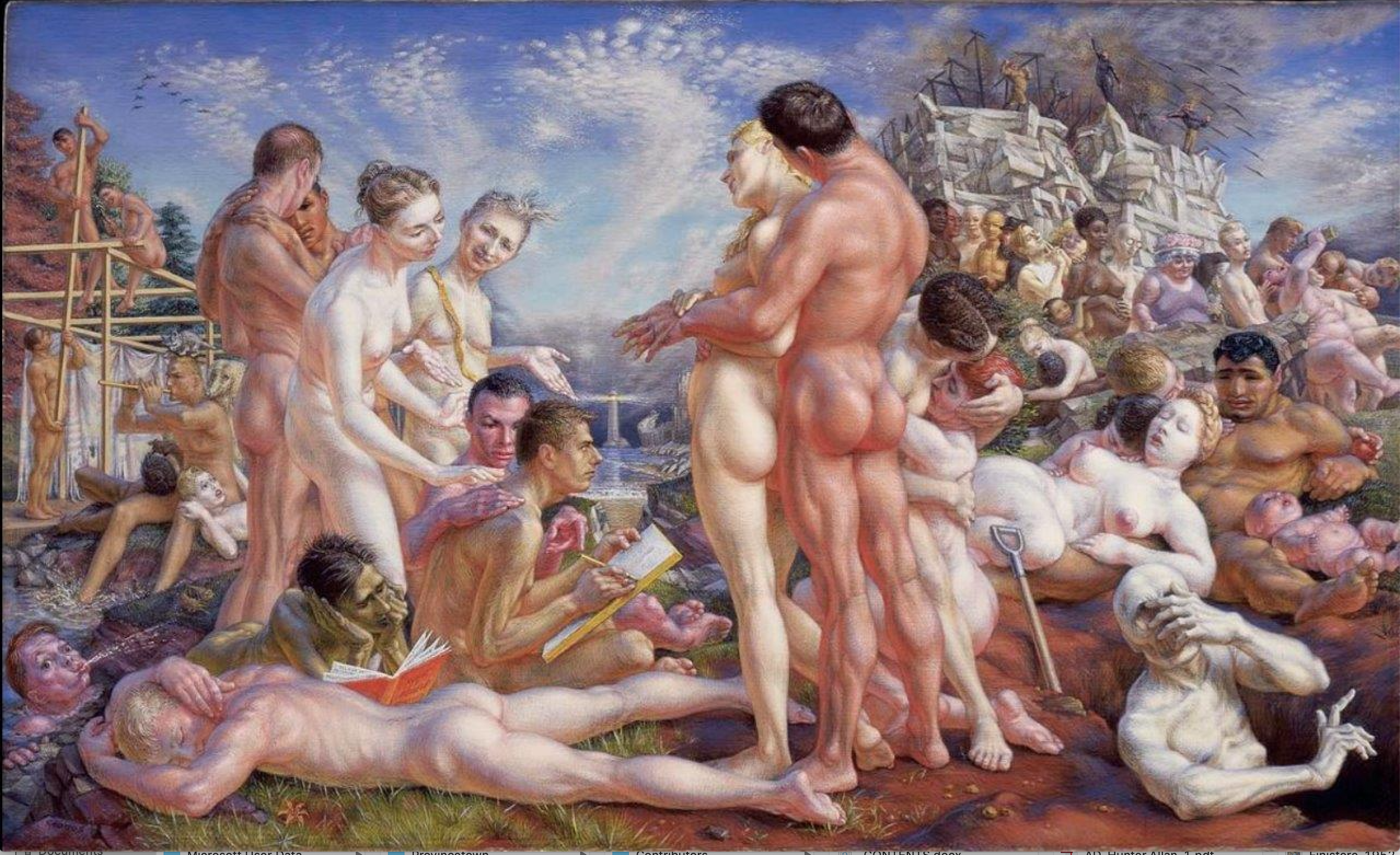

One of Cadmus’ most ambitious works is What I Believe (1948), which was inspired by a 1938 essay by E. M. Forster, with whom he forged a close friendship. Cadmus explains how “I sat on the window ledge drawing Forster’s portrait as he read Maurice to me—the gay novel that wasn’t published until many years after his death.” Cadmus admired the values that Forster wrote about—tolerance, sympathy, kindness—and shared Forster’s sense of loss over not being able to express openly the topics that were so dear to both of them. In an essay that anticipated World War II, Forster declared: “If there’s to be survival of Western culture in the coming conflagration, it’s going to be because an aristocratic ‘Community of the Sensitive’ will keep culture alive. The sensitive know each other. They catch each other’s eyes in the street”—an obvious reference to homosexuals.

Ten years later, having witnessed the destruction anticipated by Forster, Cadmus painted What I Believe (1948), in which a loving nude male couple separates the gay world from the straight. On the left, he shows a homosexual Arcadia of nude artists in a beautiful, peaceful world, with Jared French and his wife Margaret placing their hands on Cadmus. The right, straight side is an apocalyptic image of death and destruction presided over by Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini. A phallic lighthouse stands in the distance, and the clouds form a question mark, as if to ask: Which will it be?

In 1964, Cadmus met Jon Anderson (1937–2018), a handsome cabaret performer three decades his junior. While it was physical attraction that first drew Cadmus to Anderson, it was their love and collaboration that bound them together. Anderson became Cadmus’ muse, causing him to abandon his satirical, controversial work in favor of sensual, intimate drawings of Jon’s sculptural body. Philip Eliasoph, a professor who curated Cadmus’ 1981 retrospective, declared that “Cadmus’ drawings of Anderson almost single-handedly resurrected figurative art.”

“After I met Jon, I never wanted to be with anyone else,” Cadmus once remarked. Showing no sign of jealousy, Kirstein built Cadmus a house on the grounds of his Connecticut property, where Cadmus lived with Anderson for 35 years. The two cooked for Kirstein and Fidelma every Saturday. On his last day of life, Cadmus took his usual walk, got into bed with Anderson, and quietly passed away.

Cadmus stated that he belonged to a generation for which discretion signaled an unspoken ethical code. Still, by the time homosexuality was decriminalized in the 1960s (in New York), Cadmus himself—unlike Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Cy Twombly, Ellsworth Kelley, Robert Indiana, or even Andy Warhol—was already out as a gay artist. A 2019 exhibition The Young and Evil, organized by New York’s David Zwirner Gallery, finally gave Cadmus and his circle the credit they deserved. Its curator, critic Jarrett Earnest, stated: “There was another modernism beating at the heart of New York’s culture in the early 20th century. These artists were boldly homosexual at a time when it was criminalized and pathologized, expressing an otherwise forbidden and reviled sexuality.” Some works in the exhibition made modern-day viewers gasp, starting with never-before-seen drawings by Cadmus of gay sex acts.

In response to this illuminating reappraisal, a critic said of Cadmus: “No artist has been as sincere, delicate, realistic and romantic, erotic yet not exploitative about homosexuality.” Another described Cadmus as the most overlooked major American artist of the 20th century. No doubt Cadmus would have been pleased that he was no longer pigeonholed as a “gay artist” but recognized for his trailblazing work as an (unmodified) artist.

Ignacio Darnaude, an art historian and film producer, is currently developing the docuseries Hiding in Plain Sight: Breaking the Queer Code in Art.

Discussion2 Comments

So cool!!!!

Fabulous, informative and illuminating article about an artist who deserves to be recognized!