IN A CORRIDOR within the British Museum is Cupboard 55, an antique wooden cabinet numbered with a bronze plaque, containing more than 1,100 objects itemized into a registry and sequestered into an archive. It was created in 1865 and known as the Museum Secretum. Until the 1960s, the Secret Museum was a storeroom of erotica from the ancient world, including Asian, Egyptian, Greek, Near Eastern, and Roman artifacts. Many of them were objects of worship, such as pre-Christian fertility gods and goddesses. Also concealed in the cupboard were phallocentric objects, wax votive phalluses from churches in Isernia, Italy, and 8th- and 9th-century animal membrane condoms in original paper wrappers and tied with silk ribbons at the open end.

It was against this backdrop that the museum acquired the Warren Cup, a 1st-century masterpiece of Roman art from the Julio-Claudian dynasty that depicted unambiguous homoeroticism. The silver drinking cup was the largest single purchase at that time at 1.8 million pounds, and it caused something of an uproar. Observed Dyfri Williams in The Warren Cup (2006), a monograph written for the Museum: “It was prominently illustrated in all the major daily newspapers. … It was the subject of cartoons, such as a bartender serving a Roman soldier, armored and helmeted, ‘Do you want a straight goblet or a gay goblet?’” The cup presents in high relief on both sides explicitly detailed representations of two males engaged in sexual intercourse. The front scene of anal intercourse is a classical idealization of the erastes—a dominant adult male, mentor, and role model—and the eromenos—his youthful and subordinate beloved. The youth reclines onto the lap of his older partner using a leather strap as a sexual support, frequently seen in works of Greek and Roman art. The difference in size between the two figures is more noticeable on the other side of the cup, with the mature male cradling the youth and using a hand to lift a right leg to enable penetration.

Across millennia there have been representations of same-sex sexuality, some quite explicit, even without the benefit of our modern notions of sexual orientation and identity. These works were often officially banned and were produced for private consumption only, hidden from public view. Even in the 21st century, despite seismic shifts in public attitudes and changes in museums’ policies concerning sexual display, an exhibition with homosexual themes is greeted with anxious anticipation by those who follow GLBT art and culture.

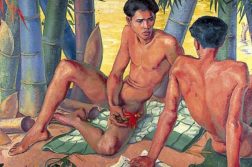

The Leslie-Lohman Museum in New York City’s SoHo district is the first and only museum dedicated to gay and lesbian art in the U.S. The museum’s main mission is to exhibit, preserve, and promote gay and lesbian art and artists. Earlier this year, the Leslie-Lohman presented a kaleidoscopic exhibition titled Medium of Desire: An International Anthology of Photography and Video to explore cross-cultural differences in desire, beauty, and sexuality. The exhibition was curated by Peter Weiermair and brought together fourteen international artists from ten countries: China (Hang Ren), Germany (Daniel M. Schmude), Great Britain (Anthony Gayton), Greece (Dimitris Yeros), Italy (Paolo Ravalico Scerri), Japan (Tomoko Kikuchi), Russia (Alexander Kargaltsev), Thailand (Ohm Phanphiroj), and the United States (Greg Gorman, Will Light Johnson, Rolf Koppel, Joseph Maida, Matthew Morrocco, and Jessica Yatrofsky). Let me highlight a few of the more interesting works that the exhibition displayed.

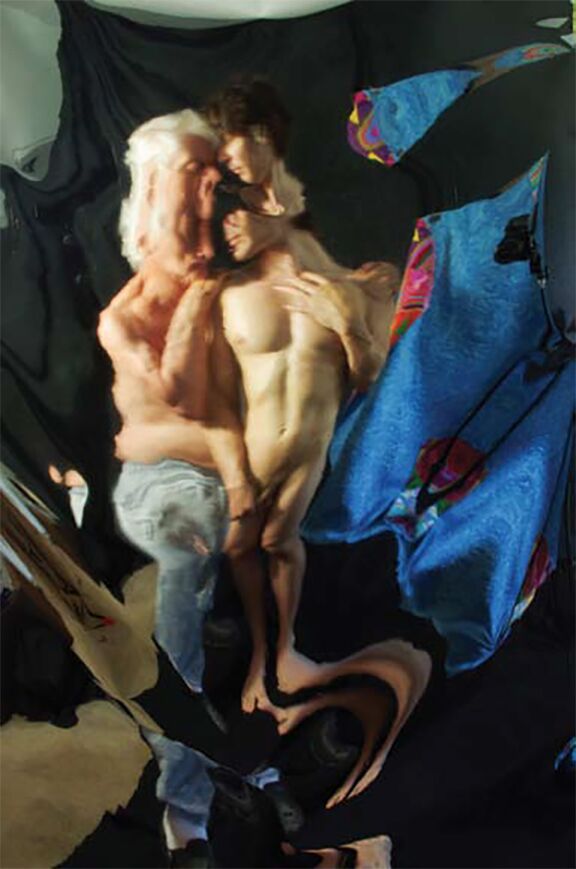

Rolf Koppel’s photograph Together in a Black Box is an unequivocal quotation of the Warren Cup, arranging the same constituents in erotic embrace: the classical archetype of male-to-male love and desire expressed sexually as the confluence of a dominant older man and a submissive youth. Indeed, the German-born Koppel, who emigrated to the U.S. with his family in 1939 and grew up in Flushing, New York, considers himself to be a classicist. He expresses contradictory views on same-sex love in his art, writing on his website that “the idea of ‘gay art’ seems ludicrous to me,” but asserting in the exhibition brochure that “it was for a gay man to introduce into photography, out of the very irrefutable force of his innate feeling and conviction, the sense of the subject, of the image itself, as conduits of a larger meaning.”

Koppel’s dilemma underscores the apprehensions about the viability of “gay art” and its commercial potential in the fierce world of straight-male-dominated museums and galleries. Perhaps unwittingly, the conflict is expressed by museum director Hunter O’Hanian when he asserts a universality of desire, optimistically writing this in the exhibition catalog: “Regardless of one’s sexual orientation, or country of origin, feelings of desire, when successfully represented, can serve to minimize our differences and bring us closer.” The statement may be commercially expedient, an attempt to reach the widest possible audience and avoid alienating potential visitors who might be put off by explicit images of same-sex eroticism. Nevertheless, the reality is that Medium of Desire, and the Leslie-Lohman Museum in general, does not minimize our differences but instead challenges the heterosexual hegemony, presenting photographs that are dissident and queer, hyperbolic and even disturbing.

British-born photographer Anthony Gayton writes in the exhibition catalog: “For me, desire is neither for beauty-made-flesh nor for the soul, but for power through ownership: the kiss of possession.” His photograph titled “The Collector” is a campy, anti-establishment nose-thumbing tableau of two plastic Ken-doll-like gay males embracing in a museum exhibition hall lined with rows of statues of athletic, godlike Greek warriors, only now most of them have erect penises. The exhibition catalog includes a poem called “The Collector” to accompany Gayton’s work: “He fed them on fine wine and cheese. Promised cash if they fell to their knees. Knowing boys without wealth, in the prime of their health, are usually eager to please.” The poem refers to the commoditization of marginal youths, sexual trafficking, and the inevitability of sexual colonization and exploitation when desire proliferates in a free marketplace.

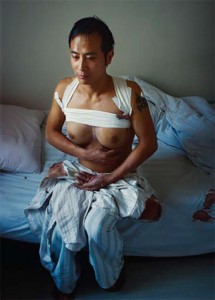

Photographer Tomoko Kikuchi was born in Tokyo but is currently living and working in Beijing. She writes in the exhibition catalog that a shift in attitudes about sexuality has occurred in China from a “dark time” toward an era of more personal freedom: “The awareness of sexuality in China has undergone a phenomenal change. Now the younger generation openly strolls in major cities, proudly expressing their sexuality.” Her Xiaozhang sitting on the bed after breast implants surgery is from her “I and I” series, which was made in Beijing when she was given access to off-limit backstage areas in order to photograph transgender performers. The image of Xiaozhang is visually complex and emotionally disorienting, starkly illustrative of the complex difficulties that transgender people encounter. For all the reports and shows in the media, being transgender isn’t fundamentally about fashion and cosmetics, and making a living for many means engaging in dangerous and life-threatening sex work or being a barroom entertainer.

Ohm Phanphiroj, who was born in Thailand and lives and works in Atlanta, Georgia, writes in the catalog that “photography is unarguably the most powerful form of visual stimulation.” His Untitled, drawn from his series “You Will Be There,” is a reference to the hooded Iraqi prisoners of Abu Ghraib and one particular prisoner who was placed on a box with wires attached to his fingers, his toes, and his penis.

The phrase that comes to mind is that of Abigail Solomon-Godeau, who writes of “torture-as-spectacle” in her essay “Torture and Representation: The Art of Détournement” in the 2012 anthology Speaking about Torture: “Various acts of torture are not only frequent in movies and television, but are now a trope in fashion photography.” In 2004, as photographs of torture by Americans at Abu Ghraib Prison in Iraq started to emerge, Susan Sontag wrote about the misappropriation and eroticization of torture (in an essay titled “Regarding the Torture of Others”): “Perhaps the torture is more attractive, as something to record, when it has a sexual component. … In fact, most of the torture photographs have a sexual theme, as in those showing the coercing of prisoners to perform, or simulate, sexual acts among themselves.” Phanphiroj’s image is disturbing in an era when photographs in various genres exhibit an intermingling of torture with clothing design and fashion, with film and television entertainment, and with eroticism and sexual desire.

Simon Baker, senior curator of international photography at London’s Tate museum, writes in Aperture magazine: “Posing, role-playing, or staging a tableau: the impulse to perform before the lens has been a fixture of photography from the beginning.” Although selfies as a genre are derivatives of the self-portrait, they are more performative than descriptive. Russian-born photographer Alexander Kargaltsev, who lives in New York City, is represented in the exhibition by two selfies that are like Narcissus self-reflectively falling in love with himself at the water’s edge. Declares Kargaltsev in the catalog: “The selfie is the medium of desire—no doubt about it.” He seems inspired by Lou Reed’s lyrics, “I’ll be your mirror, reflect what you are,” with tightly framed selfie images that capture gazes and gestures, sliding into homoerotic performance with self-caresses and expressions of sexual feeling during the acting out of love and desire. American-born photographer Matthew Morrocco’s self-portraits are performative tableaus with sexually charged homoerotic themes.

The expression of desire, gender, identity, and sexuality has been confronted variously from Tennessee Williams in A Streetcar Named Desire to Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality; from Andrea Dworkin’s feminist analysis in Intercourse to outercourse as a safer-sex strategy during the high (or low) point of the hiv-aids plague. Since the very beginning of photography, its power to communicate both feelings and ideas has been recognized. Photographs have the power to move people and ultimately bring about social change. It is why exhibitions by GLBT artists matter.

Philosopher Judith Butler has questioned the ability of language to describe or represent the authenticity of personal identities. In Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly (2015), she seems to be at an impasse when she poses the following question: “Are there forms of sexuality for which there is no good vocabulary precisely because the powerful logics that determine how we think about desire, orientation, sexual acts, and pleasures do not allow them to become legible?” Remarkably, in Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court decision that declared sodomy laws unconstitutional, a sentence from a previous decision, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, is quoted: “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” Butler’s dilemma is partially resolved when the individual’s right of self-determination—including self-defined gender identity and sexual orientation—is understood to be absolute, regardless of the vocabulary that’s used to name any particular mode of desire.

Steven F. Dansky is the founder of Outspoken: Oral History from LGBTQ Pioneers and the author of the new book Protest!: Photographs of Social Justice in the 21st Century.