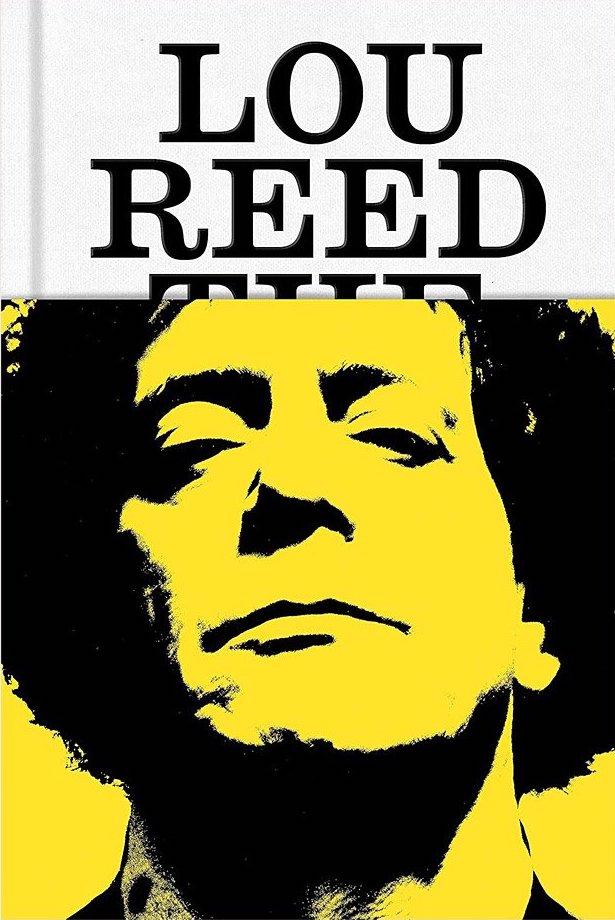

LOU REED: The King of New York

LOU REED: The King of New York

by Will Hermes

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

529 pages, $35.

AS A WRITER and commentator for Rolling Stone and NPR, Will Hermes has zestfully illuminated the zeitgeist of various musical movements, placing them within their historical and cultural settings. His latest book is an examination of the complicated genius of Lou Reed, the drug-taking, gender-bending avatar of the leather, goth, glam, and punk music scenes. Many books have been written about the legend, but Lou Reed: The King of New York may well be the definitive biography.

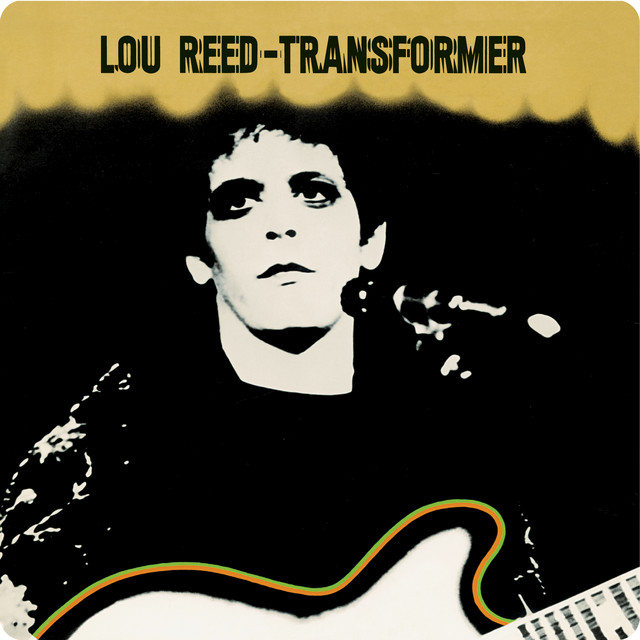

Hermes provides a detailed catalogue raisonné of Reed’s early Velvet Underground albums and examines his later recordings, including the David Bowie-produced Transformer, which featured “Walk on the Wild Side” as well as recordings that were ignored at first (but now venerated): the operatic “Berlin,” the nihilistic “Metal Machine Music,” and the politically charged “New York.”

Reed’s early life was undistinguished. Growing up on Long Island, he played doo-wop in a high school band. In his first year at NYU, he had an emotional breakdown and underwent electroconvulsive therapy. It’s not clear whether he was treated for depression or for being gay. He was an unreliable source about his own history. Researching the biography, Hermes found the musician often changed stories about his past depending upon the audience. In 1960, he transferred to Syracuse University, where he met guitarist Sterling Morrison and contracted hepatitis from dirty heroin needles. After graduation, he quickly thrived in New York’s avant-garde scene, performing at happenings with Morrison, along with John Cale droning on his viola and Moe Tucker playing drums. The group called themselves the Velvet Underground.

The quartet fell into Andy Warhol’s demimonde, with its drag queens, starlets, sex, drugs, and all forms of artmaking. Warhol offered to produce the band’s album but insisted that the German model Nico join the group as their chanteuse. Warhol got top billing on the front cover via his (now infamous) silkscreened photograph of a banana. The Velvet Underground & Nico were only billed on the backside of the album. Because of its dissonant sound and transgressive lyrics, the record garnered little radio play. Within a year, Nico was out, and Reed fired Warhol. After the group’s second release, the jazz-inflected White Light/White Heat, went nowhere, Reed kicked Cale out of the band. The remaining members soldiered on for two more studio albums before Reed finally left in 1970.

Over time, these early records have achieved cult status, their songs covered by David Bowie, Patti Smith, R.E.M., and Cowboy Junkies, among others. Reed once joked with Brian Eno that, although sales for these albums were meager, “everyone who bought a copy started a band.” During the ’70s and ’80s, Reed’s perpetually shapeshifting musical output (and provocative personas) made him the godfather of indie/alt rock. While his street cred grew, much of his output at this time was initially maligned. In addition to music, the restless Reed continued to pursue prose writing at a high level. His pieces appeared in The New Yorker and The New York Times Magazine, and he published three photobooks.

In 1989, Reed and Cale reunited to present Songs for ’Drella: A Fiction, a stark, elegiac homage to their estranged mentor Warhol, who had died two years earlier. (Their nickname for him was “Drella,” a contraction of Cinderella and Dracula; Reed was called “Lulu,” according to Cale.) Performances premiered at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival.

Amphetamines, heroin, cannabis, and alcohol fueled Reed’s prodigious output, but this appetite wreaked havoc on his bandmates, road crew, colleagues, friends, and family. Hermes delves into the musician’s destructive behavior, particularly toward Cale, the ethereal violist whose monotonal surround sound provided such an effective contrast to Reed’s four-chord beats and primal lyrics. Another target of Reed’s misbehavior—in this case, domestic violence—was Rachel Humphreys, his trans partner during the ’70s.

Reed and Humphreys separated, and the musician married Sylvia Morales in 1980. She helped Reed get clean and successfully licensed his work for use in films and commercials. After divorcing Morales in 1990, Reed blissfully settled down with multidisciplinary artist Laurie Anderson. They became the quintessential New York hipster elders before Reed died, after a failed liver transplant, in 2013 at the age of 71. Even as he was beset with failing health, Reed was planning new projects.

Anderson described his death to Hermes: “His hands were doing the water-flowing 21-form of tai chi. His eyes were wide open … He wasn’t afraid.” Lou Reed’s final words: “Take me into the light.” In eulogies, poet and musician Patti Smith called him “our generation’s New York poet, championing its misfits as Whitman had championed its workingmen and Lorca its persecuted.” Singer Michael Stipe praised him as a “queer icon” who, in the late ’60s, “proclaimed with beautifully confusing candidness a much more 21st century understanding of a fluid, moving sexuality.”

Will Hermes reveres Lou Reed’s music, and he expounds on his love in this voluminous, well-researched biography. Each of Reed’s albums is accompanied by discussions filled with riveting backstories and sympathetic analysis of his songs. So, on the one hand, Lou Reed: The King of New York is a delightfully deep dive into what looks to be a canonical legacy. On the other hand, Hermes should also be credited for not shying away from the harsher realities of Reed’s life: the abusive behavior driven by his personal demons. He was a brilliant but flawed monarch.

John R. Killacky is the author of Because Art: Commentary, Critique, & Conversation.