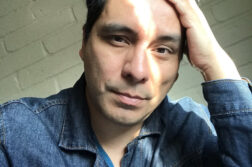

WHEN Cincinnati-born poet, essayist, and teacher Sjohnna McCray succumbed to diabetes last summer, barely making it into his fifties, he left behind a trove of remarkable work. Much of it is included in his award-winning book Rapture, a debut poetry collection that plumbed the complexities of growing up in a family with aliases—the studious son, the hardworking Vietnam veteran father, and the demure Asian mother: “In my family we all had our secret identities.” As someone who also grew up with secrets, McCray’s work speaks to me.

McCray confesses it took most of his life to write Rapture and that his motivation in writing it was to speak to anyone who felt like an outsider. “I mean, my mother was a severe schizophrenic, manic-depressive prostitute and my father drank too much. I was biracial before being ‘multicultural’ was widely accepted. It took me a long time to embrace such oddity—hopefully, the poems will make some other odd person feel more at ease.”

McCray’s childhood was tumultuous. When his mother left the family, he was raised almost entirely by his African-American father and his father’s family. McCray’s poems chronicle a boyhood spent acutely aware of the ways in which he and his family defied the heteronormative, white, upper-middle-class “standard issue” of American identity. “I didn’t want people to notice the slant of my chinky eyes, the frizz of my half-breed hair, or the smoker’s teeth complexion of my skin. … I wanted the paleness of my classmates with their straight Barbie hair.”

Reading Rapture leaves one with the sense that McCray grew up longing for a life in which he could feel at home with himself. In a poem about his early sexual longings, “Puberty in a Jar,” he describes the subtle moments of attraction he felt as a child when he and a friend hunted for salamanders. “We disturb stones/ on the bottom of the creek./ Clouds of sand and silt/ waft out—dirty thoughts/ underwater.” Like McCray, I grew up submerged by secrets—my father being a spy and my attraction to girls. For us, secrecy was like a member of the family. It has taken a lifetime of words and work to come to terms with myself. Similarly, McCray seems always intent on tracking his own authenticity, stripping away what is not true or not helpful. In “Just the Facts, Ma’am,” McCray examines his complicated connection to his mother through the lens of illness—his mother’s and his own. When a Cincinnati coroner calls to inform him that his mother, missing from his life for nearly 28 years, has died, a call he has long expected, McCray is at dialysis, sitting in a pink recliner, being treated for diabetes. The coroner says his mother’s body was found in a parking lot next to a metal garbage can. McCray remembers being a boy, confused by her illness and behavior. “When I was little, I used to watch her standing at a bureau and furiously scribbling her notes on paper until she filled every inch, not just horizontally but in the margins and along the edges. She’d do this until she needed another white sheet and off she went—documenting an invisible life—at least not visible to me.” McCray’s most moving writing is reserved for his partner, someone he says eventually replaced his father as his entrée into the world of art and feeling. In “Blue Heron,” he describes meeting his partner for the first time. I was struck when I read this poem by its feeling of expansiveness, the sudden emotion he has plunged into, and how he achieved transcendence so quickly. “When we first met, you stuttered as if the words/ dipped down on the diving board of your tongue/ before launching into air, the triple loops/ of earnestness of those first talks. … You seem/so wild to me—your pale neck and backwoods/ habits. A luxury to see a man up-close.” McCray died before his plans for a memoir and a second volume of poems could come to fruition. Still, his stubborn honesty and his striving to bring into light all the facets of his identity, no matter how ugly or painful, is an example for all writers struggling to embrace their identity. But McCray emphasizes that beauty can be found at the heart of each of our lives, no matter the complexity or trauma. It was McCray’s intention as a writer to invite into the room anyone who felt on the margins. His words are like a homecoming for me, a respite from a world that divides, offerings from a writer who has achieved self-acceptance and who generously welcomes us all into the circle. Sjohnna McCray died in June of 2023. He was 51.