GREASEPAINT PURITAN

GREASEPAINT PURITAN

Boston to 42nd Street in the Queer Backstage Novels of Bradford Ropes

by Maya Cantu

Univ. of Michigan Press

329 pages, $29.95

IN AN EARLY SCENE in Warner Brothers’ hit musical 42nd Street (1933), Peggy Sawyer, a naïve aspiring actress, accidentally walks into the dressing room of Billy Lawler, a young, good-looking actor who’s getting ready for a Broadway show rehearsal. Billy (played by Dick Powell), caught wearing only his underwear, jumps up in surprise and yells at Peggy (Ruby Keeler), who had mistaken him for the show’s stage manager. “Weren’t you expecting me?” asks the startled and confused Peggy. “Well, not exactly,” answers Billy. “But I’m afraid you’ll do.”

As a gay man himself, Ropes would have been very familiar with the sexual politics of Broadway and Hollywood. Shortly after finishing high school in Quincy, Massachusetts, in 1921, the theatrically gifted Ropes moved to New York and began a successful career in vaudeville. An exceptionally talented dancer known for his high kicks, the eighteen-year-old Ropes adopted the stage name “Billy Bradford” and was soon performing in Broadway’s most prestigious vaudeville theaters. For the next ten years, Ropes was a luminous presence on the vaudeville circuit, touring extensively throughout America and Europe, where he was lauded by critics as the “elastic, double-jointed man.”

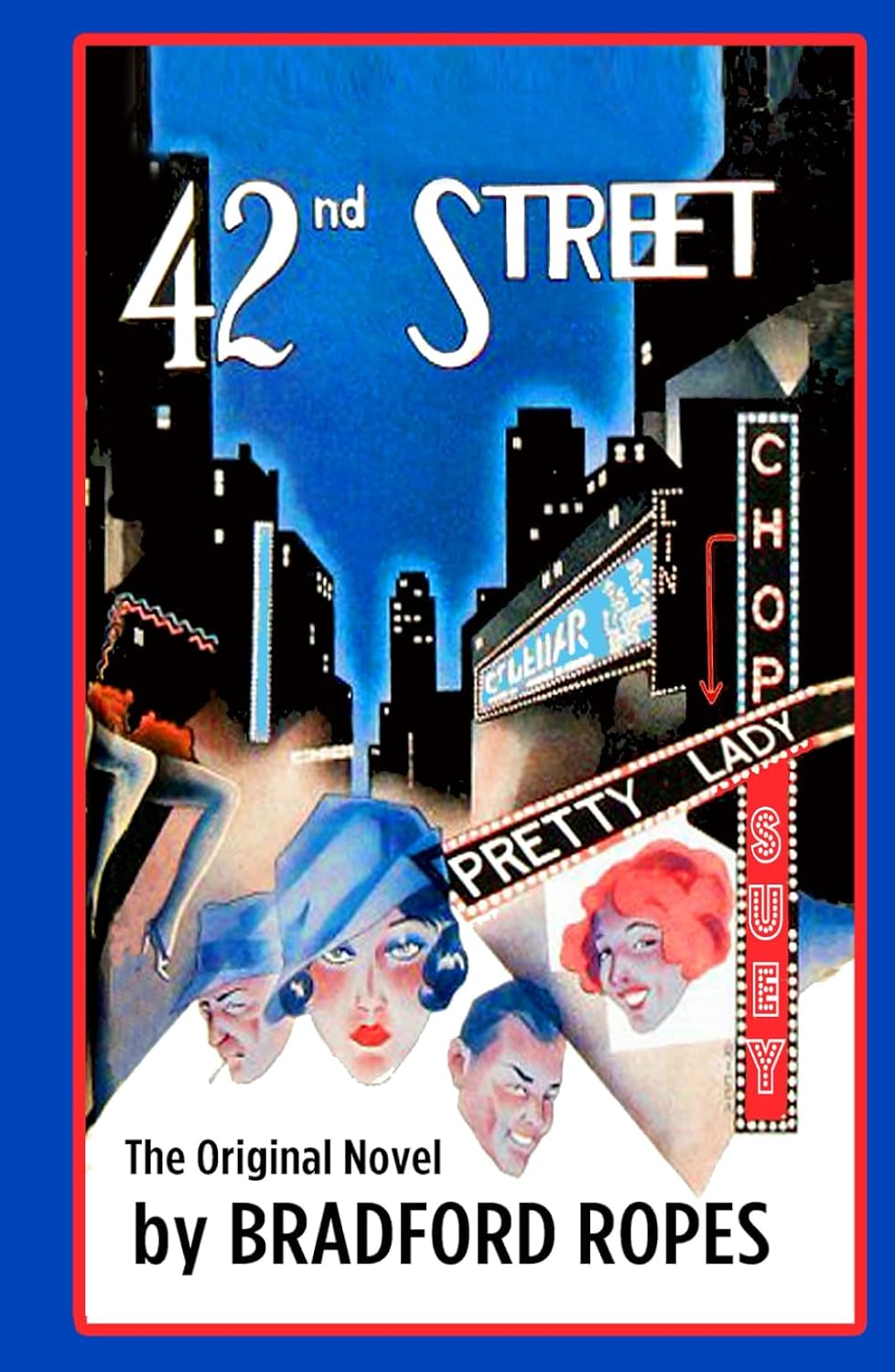

By the early 1930s, however, vaudeville was in steep decline, in part because of the popularity of motion pictures but also because of the rise of “elite modernist literary drama” associated with playwrights like Eugene O’Neill. Sensing that his dancing days were numbered, Ropes turned his attention to writing and, while still on tour, wrote the manuscript for 42nd Street, a backstage novel about a fictitious Broadway musical production. The novel was a minor sensation and the movie rights followed almost immediately. Ropes wrote two more backstage novels, Stage Mother (1933) and Go Into Your Dance (1934), likewise fictionalized accounts of the Broadway theater scene of the 1920s. He eventually settled into a busy career as a Hollywood screenwriter, churning out reliable comedies like Laurel and Hardy’s Nothing But Trouble (1944) and Abbott and Costello’s The Time of Their Lives (1946). Eventually, however, Ropes found it hard to adjust to the changing film industry, and in the early 1950s he moved back to Boston and started writing novels again. When he died unexpectedly in 1966, he was at work on several novels, including a biographical novel about the Broadway musical star Donald Brian (1877–1948).

Maya Cantu’s meticulously researched biography, Greasepaint Puritan: Boston to 42nd Street in the Queer Backstage Novels of Bradford Ropes, reveals the extent to which Ropes based his backstage novels on his own Broadway experiences. As much a work of theater history as a biography, Cantu’s impressive book recreates New York’s theatrical scene in the 1920s, a business that provided new opportunities for artistic gay men but that also strictly circumscribed their behavior by forcing them to conceal their sexual identity and bolster the image of straight, middle-class masculinity. Through a sensitive reading of the novels, Cantu shows how Ropes imagined a “queer resistance” to the theater’s inherent homophobia through the figure of the chorus boy: the ubiquitous (and typically gay) Broadway performer who responds to his stigma in the business with a sharp tongue and a “camp” sensibility. No doubt Ropes saw himself as such a figure.

Cantu does such a thorough job of establishing the theatrical and literary milieux of Ropes and his novels that at times Ropes himself almost recedes into the background. For example, the last fifteen years of his life, which saw some of the most important changes in his career and relationships, are briefly sketched out in the book’s last chapter. His ten-year relationship with the musician Roswell Jolly Black—probably the most significant romance in his life—merits only four pages. This lack of emphasis is partly due to the fact that Ropes left behind no personal memoirs or letters for historians to pore over. He did, however, give a number of talks and interviews in his lifetime that could have been mined more deeply for biographical material. And, as Cantu proves beyond a doubt, Ropes wrote himself into all of his novels. One of the many virtues of Cantu’s book is that it serves as a call to rediscover and read Ropes’ backstage novels—not only for what they reveal about the history of American theater, but also for what they reveal about the life of an important gay figure who might otherwise have been forgotten.

Joseph M. Ortiz, professor of English at the University of Texas at El Paso, is the author of Gordon Merrick and the Great Gay American Novel.