Writing a Chrysanthemum

Writing a Chrysanthemum

The Drawings of Rick Barton

Edited by Rachel Federman

DelMonico Books

144 pages, $49.95

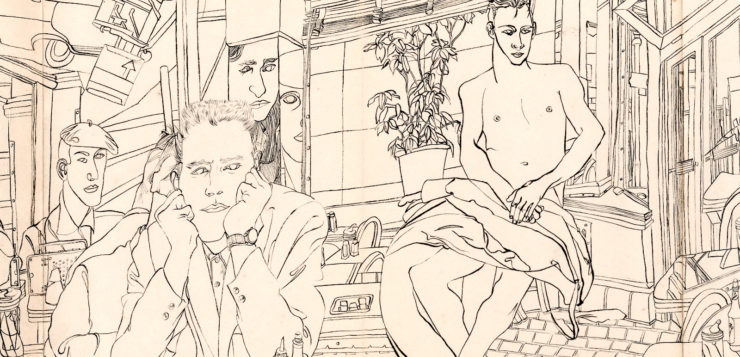

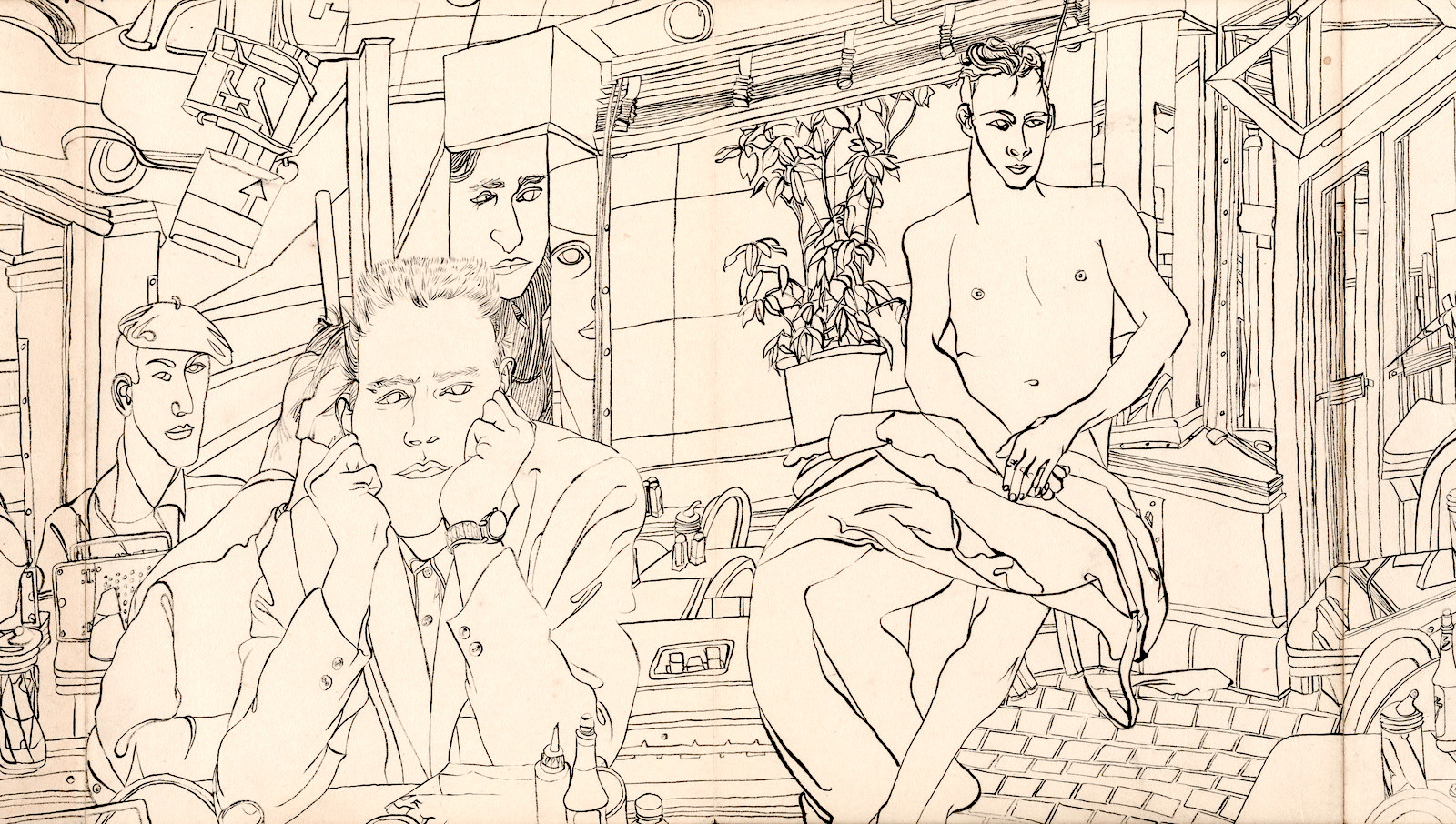

I SPOTTED HIM in the city this summer, a naked young man sitting with his ankles crossed, hands clasped on the jacket thrown across his lap. This banner-sized reproduction of a drawing hung outside New York City’s Morgan Library & Museum to advertise a new show by an artist I had never heard of. Something about the affectionate rendering of the male form made me certain he was gay.

That hunch was confirmed in both the show and the accompanying book Writing a Chrysanthemum: The Drawings of Rick Barton. Born and raised in hardscrabble circumstances, Barton (1928–1992) got his art education from visiting the city’s museums and the New York Public Library. He dropped out of high school, enlisted in the Navy, and was discharged, possibly for mental illness, settling in the Bay Area in the 1950s like many gay men of his generation. A self-described paranoid psychotic, he self-medicated with alcohol, marijuana, and opium, and obsessively drew pictures. He attracted a group of acolytes who congregated in coffee shops and gay bars, including the Black Cat Café, and instructed them in drawing using Chinese and Japanese tools and traditions that he probably picked up while in the service. Drawing seems to have been a kind of meditative practice for Barton, not so much an act as a state of being.

Federman organizes that work by theme: interiors (the bare bulbs of bohemian squalor sometimes illuminating nude men), architecture (ornate gothic cathedrals), public spaces (eclectic coffee shops and bars), and plants (often thin and spindly-looking). Sometimes Barton includes his hands and feet in the drawings; sometimes more than one set of each. He doesn’t do over; he just adds. Yet everything feels as if it flows from one continuous line.

Barton’s multiple perspectives within a single drawing give his work a singularity and an intriguing complexity. The line drawings often have a fragmented perspective, like a kaleidoscope, while the block prints practically vibrate with intricately carved detail. In one untitled drawing that Federman calls “Nudes,” we see mostly one man drawn over and over again, each time reduced to fewer of his body parts—a torso, a penis—yet Barton always includes the man’s feet, the scribbles of toes like little loopy flower petals. The disembodied pair of hairless testicles almost feels cartoonish, yet carries a pendulous weight.

In another untitled drawing labeled “Two figures,” a man lies in bed looking forlorn, while another sits with his back to us backward in a chair, feet stuffed into slippers, head in hand. In just a few lines, Barton conveys the broad expanse of the seated man’s back and the heft of his underwear-clad buttocks. The sensuous physicality suggests an intimate relationship, but the body language conveys emotional estrangement.

A set of accordion-folded sketchbooks is mostly filled with men, probably drawn in cafés; some of the pages look spattered with drips of coffee. The sketchbooks feel like a game of Exquisite Corpse, where a drawing is begun, the page folded over and continued by someone else, only Barton has played it by himself over time, and gone in whatever new direction the line seemed to take him on any given day. Unfolded, the scrolls bring to mind the legend of one of Barton’s Beat contemporaries: Jack Kerouac typing On the Road on a long roll of paper so he wouldn’t have to stop and risk interrupting the flow.

Writing a Chrysanthemum teems with intense, mysterious feeling. There’s something unhinged about the work (one of Barton’s benefactors called him “crazy as a bedbug and impossible to cope with”) that is both bizarre and intriguing. It defies the norms we know, as does Barton, who considered himself not an artist but a writer. The artist Etal Adnan, whose writing is excerpted in the book, likewise felt that Barton’s sketchbooks were “not meant to be grasped in a single vision like a painting, but rather to be read, visually, in sequence, like an ordinary book that you cannot read in a single glance.”

Michael Quinn writes about books in a monthly column for the Brooklyn newspaper The Red Hook Star-Revue and on his website, mastermichaelquinn.com.