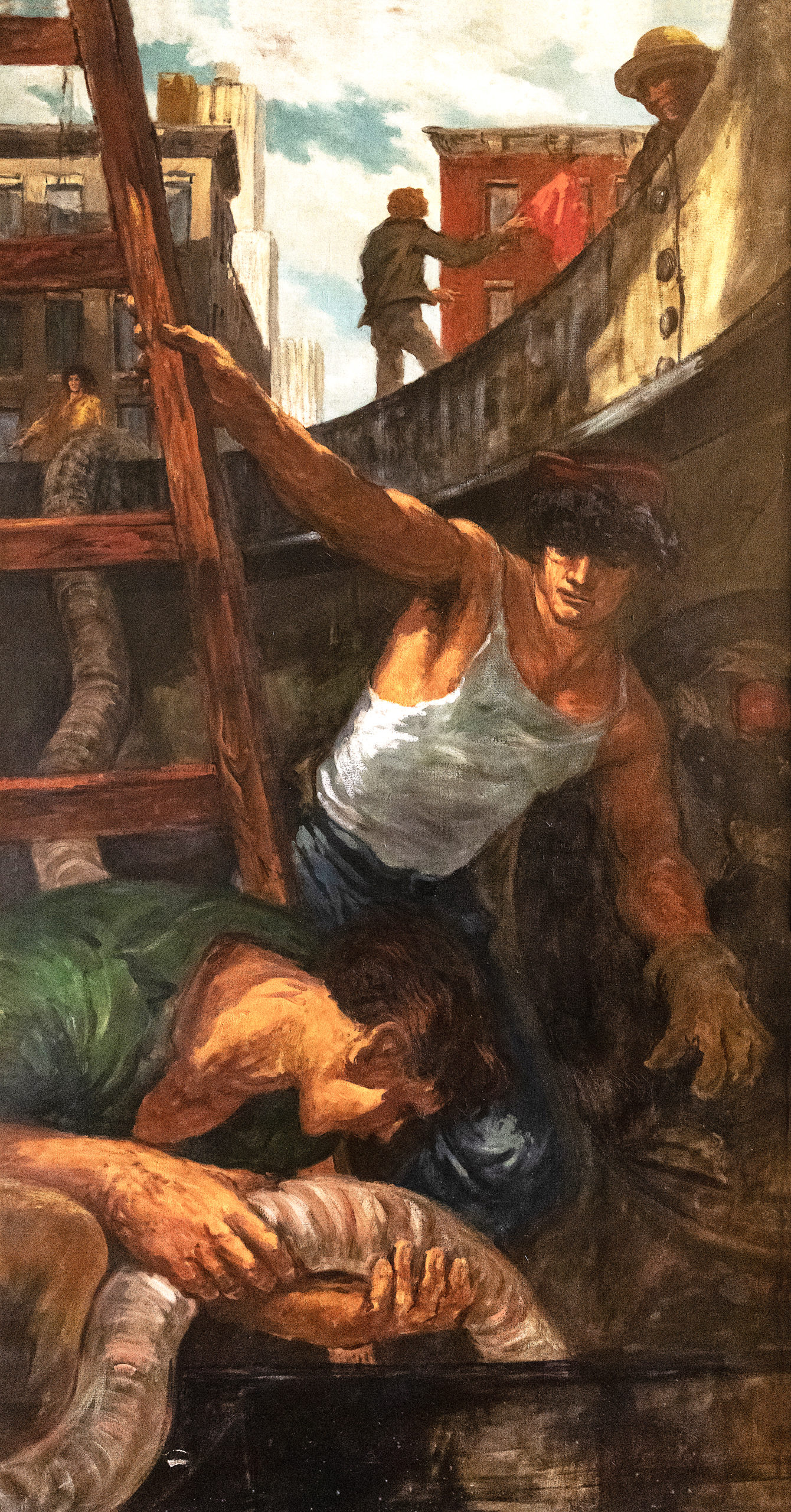

WHEN Abstract Expressionism exploded in the 1950s, Edward Melcarth was painting and sculpting construction workers, junkies, and hustlers in an epic style, highly influenced by Renaissance painters like Paolo Veronese and Tintoretto. This link between the past and present was a significant feature of his artistic vision, one that still has a striking effect on the viewer to this day. His casting contemporary scenes in a heroic model is a revolutionary gesture and worthy, at the very least, of a deeper investigation into his artwork and life.

Richard Taddei was an assistant for Melcarth and remained a close friend and associate until Melcarth’s death in 1973. His own paintings are usually concerned with male nudes, but (unlike Melcarth) in semi-abstraction, or in a style that Taddei describes in this interview as “Cubist.” Taddei studied at Pratt Institute and has exhibited widely. The Leslie-Lohman Museum owns a number of his paintings, and his work can be found in the private collections of John Loring, Malcolm S. Forbes, Robert Stigwood, Princess Minnie de Beauvau-Craon, Reed Massengill, and many others. He currently lives in Montgomery, New York.

Taylor Lewandowski: When did you first meet Edward Melcarth?

Richard Taddei: One of my professors knew Edward. It was sheer luck. Edward was working on a mural at the Hotel Pierre and my professor said: “Why don’t you go up there with your portfolio? He needs assistants.” This was the fall of 1968, and I was so nervous taking my sketches and early artwork to him. He lived on W. 47th Street, above the Gotham Book Mart. He had the top floor apartment facing south, and his studio was full of sun. I was so impressed, because I had never met a real artist before, and he was painting these heroic male nudes, and it blew my mind. I didn’t think that happened anymore. This was 1968, and everyone at school was painting abstractions. I was so thrilled to see this realist work. It looked like the painters I idolized in the Renaissance, which was his period too. The 17th-century Venetians. His focus, like that of Tintoretto and Veronese, was on his heroes (they were mine too), and here he was painting these great, modernized versions of them. The same style with the same color palate and everything, but with modern figures and modern settings.

Anyway, he was so charming and fun to be with. I remember it was the top floor, and I was so out of breath. I was 22, I guess. So, he hired me to help him with the hotel and paint this huge mural—which is still there. I was under his eye for a long time, so in the early years my paintings were much like his paintings, but I evolved. You have to. Every artist has to form his own style, but it was all based on Edward’s inspiration. I’m still painting male nudes, but they’re abstracted—well not abstracted, but kind of cubist. They’re very sensual.

TL: When did that shift happen from a realist approach à la Melcarth to the more abstract approach that has defined your style?

RT: During the ’70s. He died in 1973. It was a shock, because he was only 59. But he was so overpowering; after his death I was able to break free. He was very dogmatic about the way things had to be painted, which is good for a while, but then you have to search your soul and figure out where you’re going to go. Every student of a great artist or writer must find their own style sooner or later; otherwise it looks like they’re just a grade B version of the master. I’m very headstrong, so I had to make my own statement. I don’t know if it got me anywhere, but I’m happy with all the paintings I’ve done, and I’m still going crazy painting, but it’s not easy to make money from it. I’ve had some success, and people are collecting my work. Malcolm Forbes liked my work. I met him through Edward.

TL: Did Edward ever talk about early 1950s New York, or about his time overseas?

RT: Oh, yeah. All the time. He was a great storyteller. He used to tell me about these adventures he had in Times Square, and all the hustlers and other people he ran into. He knew Gore Vidal, people like that. Tennessee Williams. That was the ’50s and ’60s. It was that whole period, and I just caught the end of it. We would go to 42nd Street very late at night, cruising. Sailors were still around, because the Navy Yard was still there. He introduced me to his rough trade world, which was not my world, but they inspired him and they modeled for him. It was this dual thing, and I did that as well. I would pick up guys who were my type, and they’d model for me, and I kept doing that until a few years ago. That’s how I got my wonderful models. They were bartenders, waiters. Or some photographer friend of mine would say: “I have this great model; why don’t you come meet him?” And if it worked out, I would hire him. I was in the city for 48 years. I sold my apartment and moved upstate, back to nature, which was something I always wanted to do. I have a house with a beautiful studio that has a skylight, which I’ve always wanted.

TL: What role did Venice play in your lives?

RT: Edward moved to Venice in 1970, and I occasionally visited him. That was a very fortunate period for me. He introduced me to a lot of fascinating and unusual people. He introduced me to Peggy Guggenheim, who lived there at the time and had this great collection of surrealist and abstract art, which Edward hated, but they were great friends, and I was thrilled to be there.

One of his favorite artists was Canova—very classical, 18th century. His hometown was in the Alps above Venice. Edward always wanted to go there. There’s a museum with all the plaster casts from his great sculptures, so we took this bus up the mountains. It was a whole day getting there and a whole night getting back. It was a big trip. It was a very memorable experience to be with him, seeing his idol’s work. Edward did these very erotic, male semi-nudes, like a foot and half high, made of bronze. He was doing it while I was there. He had this grand plan for them too. It’s a shame he died so young.

TL: What was his grand plan?

RT: There was a Tower of Babel arrangement. I still have the sketches for it. He also wrote a lot. I have copies of his manuscripts, but I donated everything to the Smithsonian. His writings on art are fascinating, but his theories don’t hold water. He made these grand pronouncements that were always over-generalized. It drove me crazy. Everybody’s this, everybody’s that. And you have to paint this way, and you can’t paint that way. But he was such fun to be around. I was fortunate to have met him. He was a major, major influence.

Taylor Lewandowski has contributed to Arazi magazine and NUVO, and recently curated a photography book, Pathology (Nightlife Books).