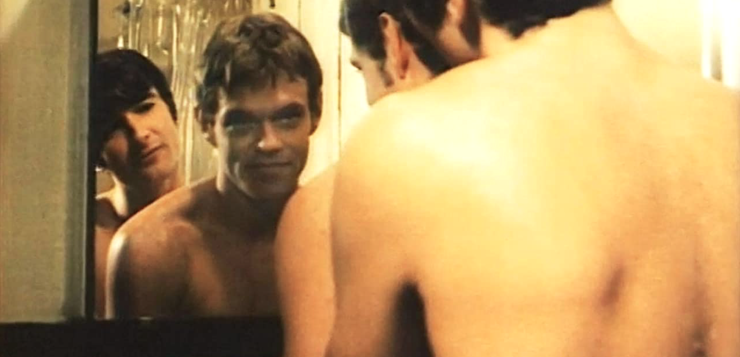

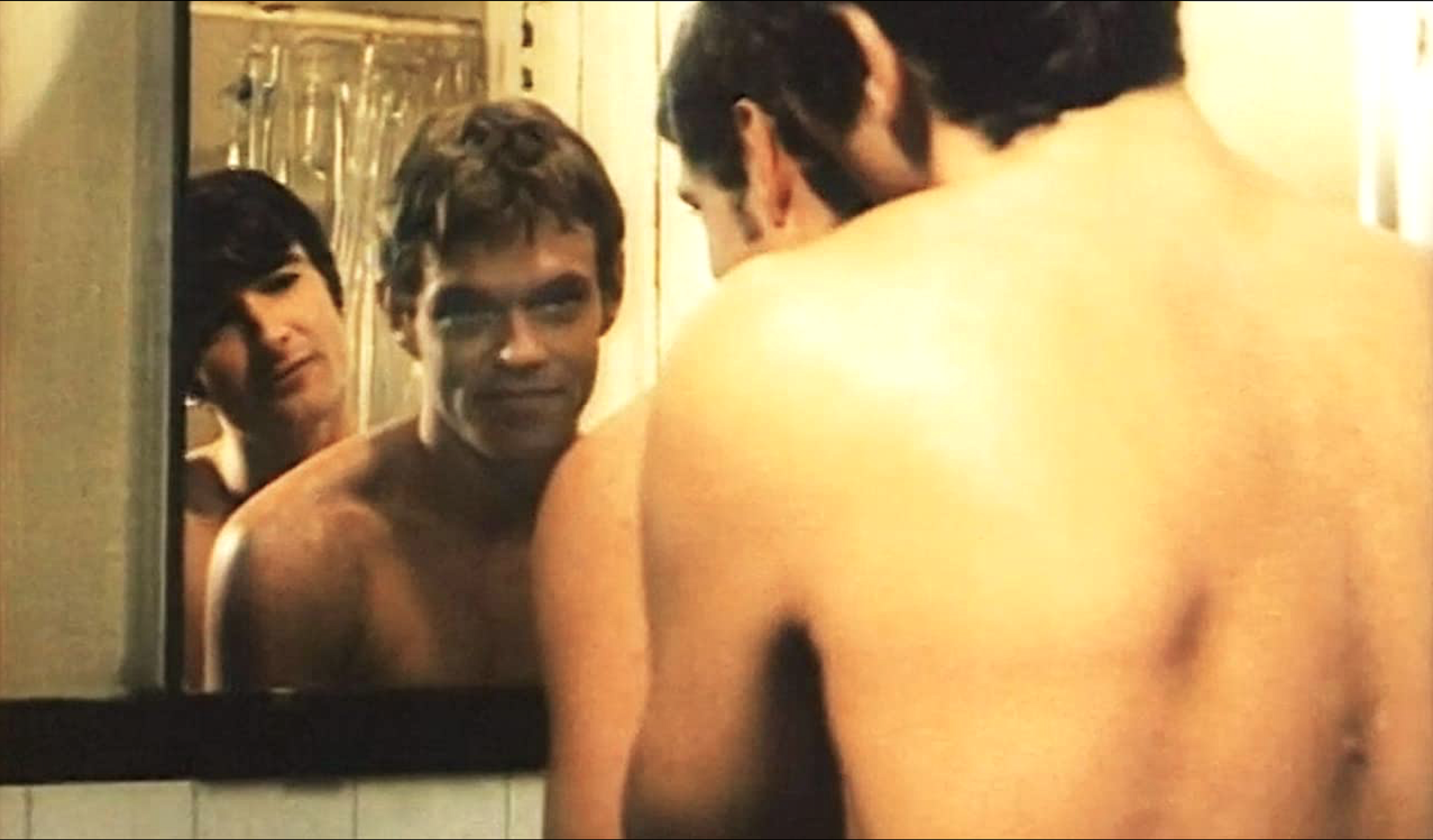

SOMETIMES coincidence is all we need to see that modern gay life unfolded in America even outside those vanguard movements that began with the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis in the 1950s, then coalesced in more radical forms after Stonewall. I became aware of an untold history recently when Amazon Prime added the early gay film, A Very Natural Thing, to its streaming lineup. Gay people of a certain age will recall this movie, which was released in 1974. It was one of the first feature-length, mainstream films that attempted to normalize gay people and their relationships. Watching it again gave me a new appreciation for the personal stories that helped produce one version of gay culture in the U.S., not least because I uncovered a connection between an actor in the film and the institution where I’ve taught for over thirty years.

What this discovery did, in effect, was to connect the dots between Furman University and the Sexual Revolution of the late 1960s and ’70s. A formerly Baptist school in the Bible Belt of South Carolina, Furman seems a million intellectual miles from all that. And yet, when I googled the actors in A Very Natural Thing, I discovered that one of them, Robert Joel McLane (or Robert Joel, as he was billed in the film), was a 1965 Furman grad. I found his pictures on the Furman Theatre Department website, read stories about him in archives of the student newspaper, and followed his undergraduate progress in The Bonhomie, Furman’s yearbook. I even located retired colleagues whose memories stretch back to the early 1960s, and who recalled Robert with fondness and testified to his talent.