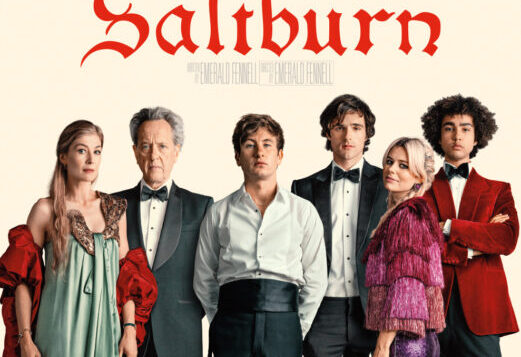

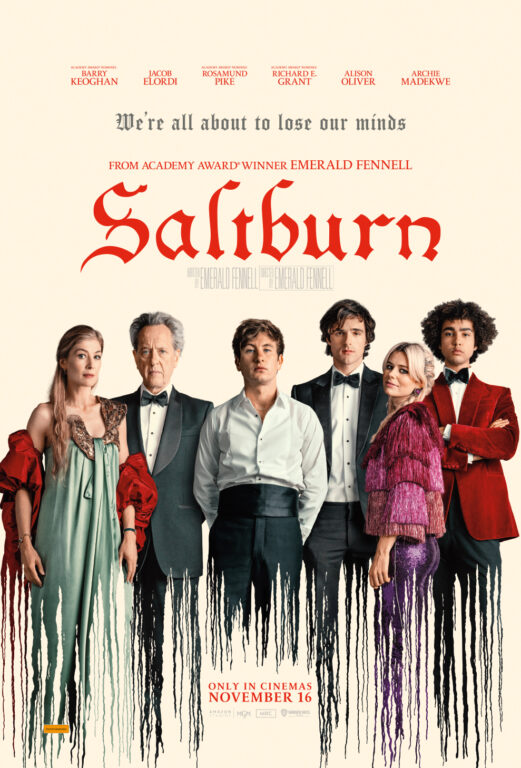

SALTBURN

SALTBURN

Directed by Emerald Fennell

Amazon MGM Studios

IN THIS AGE of biopics about famous people—Leonard Bernstein and Bayard Rustin are current examples—along with historical films about ancient Rome or World War I, it is somewhat reassuring to see a film that plays fantastically with entirely fictional creations. That would describe Saltburn, which begins at Oxford with characters seemingly adapted from Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited: a young, handsome aristocrat named Felix and a smart, middle-class student, Oliver, who was lucky to get into Oxford.

Oliver immediately becomes smitten with Felix and, as the plot unfolds, with his family. Waugh is actually name-checked early on in the film. However, he is soon left behind in a narrative that turns shades of The Talented Mr. Ripley when the middle-class Oliver (played by Barry Keoghan) befriends the super-rich Felix (Jacob Elordi). Felix brings Oliver home with him and introduces him to his family at their summer estate, known as Saltburn. We learn in due course that Oliver is steadily implementing a long-term gameplan to kill off each member of the Catton family, including Felix’ sister and mother, so that, if he succeeds, he’ll wind up inheriting everything.

This extraordinary scheme is laced with sexual perversity and queerness throughout, as Oliver

Jonathan Alexander is Chancellor’s Professor of English at the University of California, Irvine. For more about his writings, visit: the-blank-page.com.