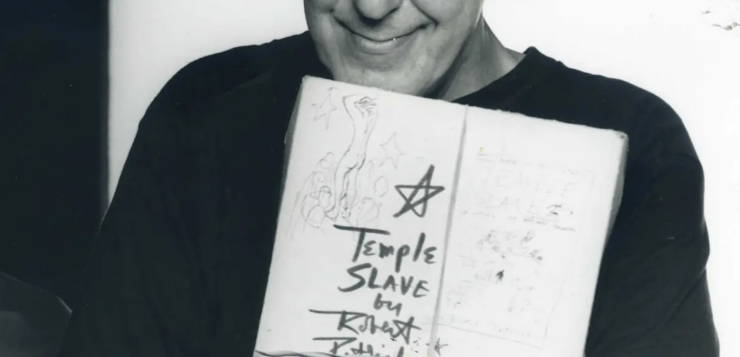

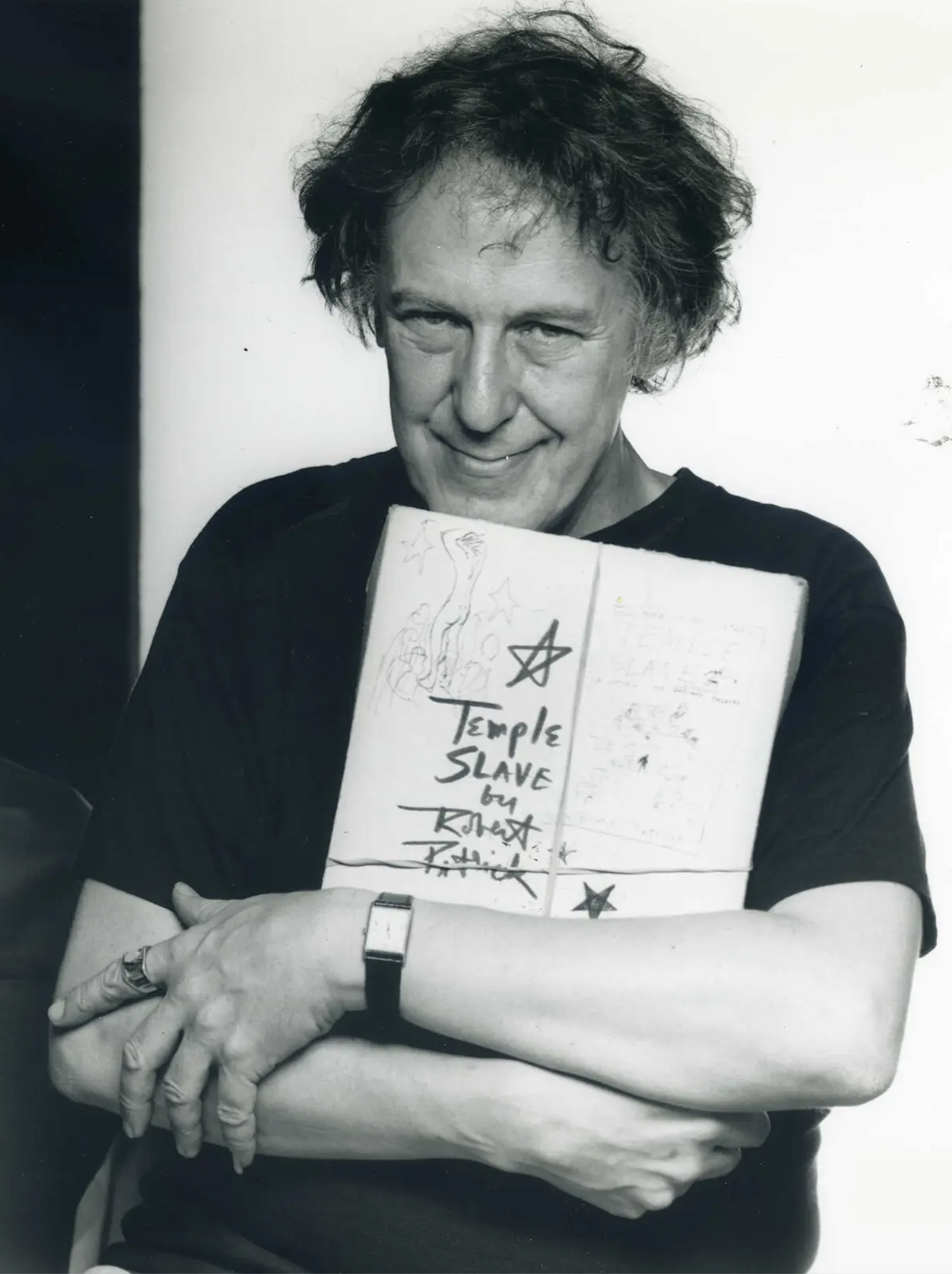

LEGENDARY PLAYWRIGHT Robert Patrick died earlier this year, on April 23rd, at the age of 85. The author of some sixty surviving plays—in 1983 he estimated that he’d already written between 250 and 300—he was described by Samuel French (the publisher of acting editions and licenser of productions of contemporary plays) as the most produced playwright in New York. But the irreverent Patrick preferred to describe himself variously as “true trash,” a “dark angel of light,” and a humble “handmaid of the arts” who was dedicated to “saving American theater.” His intention, he wrote, was to “set fire to the minds of a generation.”

Robert Patrick O’Connor—a mistake made on the poster for his first play resulted in his dropping his family name in professional matters—was born in Kilgore, Texas, on September 27, 1937. Eager to escape what he termed the “pod people of fifties America” among whom he grew up, he joined the Air Force to see the world, only to be discharged during basic training when a poem he’d written to a fellow soldier was uncovered during a crackdown on gays in the armed services. In September 1961, traveling cross-country by bus, he stopped to visit a friend who’d recently moved to Manhattan. On a street during his first day in the city, he followed a beautiful young man into a dilapidated coffee house cum theater. He was so immediately engaged by the Caffe Cino’s atmosphere of raw magic and open homosexuality that he remained there until it was forced to close following founder Joe Cino’s death in 1967.

As Patrick himself recalled later in life, the Caffe Cino was the “Ground Zero of the 1960s … a coffee-house, a theatre, a brothel, a temple, a flophouse, a dope-ring, a launching-pad, an insane asylum, a safe-house, and a sleeper cell for an unnamed revolution.” His novel was Temple Slave (1994), a fictionalized but nonetheless revealing history of the Caffe Cino, the birthplace of American gay theater. (See also Darren Patrick Blaney’s article in the January-February 2014 issue of this magazine.) The secret of the Caffe Cino’s success seems to have been Joe Cino’s rejection of the scripted and the expected. Cino refused to read the plays submitted to him for production so as to avoid creating his own expectations that might interfere with the playwright’s concept, or prevent him from enjoying the surprises that the production had to offer. (“It’s magic time,” he’d announce at the start of every performance.) And because the Caffe was so small and had no real stage to speak of, actors would move among the audience members, who were tightly packed around the coffeehouse tables, thereby blurring the boundary between the audience and the performers and creating what was often an electric connection. Also, as Stephen Bottoms, historian of the off-off-Broadway theater movement, points out, because the better part of the Caffe Cino’s staff and regular patrons were gay, the Cino became a haven for individuals excluded from mainstream society, fostering “the celebratory abandon with which Cino writers embraced the bizarre, the ridiculous and the taboo.”

The sexual freedom that one experienced at the Caffe Cino led to the sexual propositioning and even exploitation both of playwrights seeking to put on a play and of actors eager to be cast. And the success of such groundbreaking productions as Lanford Wilson’s The Madness of Lady Bright, Doric Wilson’s And He Made a Her, Tom Eyen’s Why Hanna’s Skirt Won’t Stay Down, and Patrick’s own The Haunted Host attracted the attention of avant-garde artists like Andy Warhol, who replicated the pop cultural experiments of the Cino without the Rabelaisian spirit that gave them their humanity.

There is a boisterous, even chaotic element to many of Patrick’s early plays, giving the impression that they were actually written as they were being performed. This impression is not entirely false. When the performance scheduled at the Caffe Cino fell through one evening, Patrick famously improvised by purchasing half a dozen copies of a comic book at the local newsstand and leading the actors in a hilarious reenactment of an episode of Wonder Woman. In the process, he inaugurated a vogue for campy adaptations of the codes of popular culture on the West Village stage. As Patrick recalls in his preface to the four skits written largely in the 1960s but collected under the title Up by Wednesday in 2017, it often happened in those “long ago days” that he might have been walking in his Lower East Side neighborhood only to have La Mama director Ellen Stewart call out to him: “A show canceled. Can you get something up by Wednesday?” The play that he wrote would depend entirely on the actors and costumes that Stewart had available. (His title Up by Wednesday coyly satirizes the title Up to Thursday, by Sam Shepard, who started out at the Cino—where, Patrick hints, he enjoyed receiving blow jobs from his gay colleagues, only to move on to commercial theater and heterosexual acclaim.)

What kept Patrick gainfully employed was his ability to write to the needs of any of the half dozen off-off-Broadway theaters where his plays were produced—most notably, after the shuttering of the Caffe Cino, the Old Reliable Theatre Tavern, for which Patrick wrote some thirty plays in two years, and which supplied him with a rowdy audience that he enjoyed interacting with. The theater’s very name was a reminder of the occasional, improvisational, and highly social nature of the venues that Patrick preferred. Stephen Bottoms describes Patrick’s Joyce Dynel (1969)—first produced at the Old Reliable—as “a carnivalesque travesty on the life of Christ” in which, for example, the Annunciation occurs in a scene in which “God rapes Mary, but stops midcoitus to ask his divine member, ‘What’s a nice joint like you doing in a lousy girl like this?’” Such a witty inversion of the standard pick-up line (“What’s a nice girl like you doing in a lousy joint like this?”) in the service of undercutting pious belief in the Immaculate Conception is pure Patrick. No one seemed to appreciate “the fun off-off-Broadway could be” more than he.

The same spontaneous inventiveness and almost demonic creativity that made Patrick so popular in the 1960s and ’70s are what caused his reputation to decline thereafter. The political and pop cultural icons whose momentary visibility invited Patrick’s skewering invariably lost their resonance, making it unlikely that the plays exploiting them would ever be revived. Many of the scripts were so ephemeral that, late in life, Patrick was reduced to asking on his website if anyone could share a copy of any of the two dozen titles that he listed. Presumably the plays had been improvised under his direction, and no one had bothered to make a transcript of what had apparently proven a popular but short-lived production. Perhaps most damaging to his plays’ longevity was the impossibility of replicating the zeitgeist that had provided the haphazard spark for their initial production and performance.

Patrick’s plays were inextricably linked to the Sexual Revolution of the 1960s. For example, it seems unlikely that a later production of Mercy Drop, or Marvin Loves Johnny (1973) enjoyed the challenge that the original production faced when, as Patrick explains in the preface to the printed version of the play, “two days before the opening, the very handsome and talented [lead actor]Douglas Travis … came down with the most God-awful hysterical warts on his penis. Rather than give science-fiction overtones to what is, after all, essentially a love story, he was allowed” to remain clothed. The Sexual Revolution that occurred in the streets following Stonewall was in some ways a weak imitation of what Patrick had imagined in the preceding years on the stage.

Patrick seems to have understood fairly early on that his moment of glory would be short-lived. In 1983, he abandoned New York City for the West Coast, frustrated that the surviving off-off-Broadway theaters like La Mama and Circle Rep had lost their improvisatory edge, having discovered that, in order to apply for the grant money that they needed to stay afloat, they had to announce their production season months in advance. In Los Angeles, Patrick became artistic director of the forty-seat Fifth Estate Theatre, where he could direct productions of his own plays. (On his seventy-fifth birthday he performed a one-man show about his career titled What Doesn’t Kill Me Makes a Great Story Later.) And he worked tirelessly with an organization for high school drama students, hoping to instill in the next generation the reverence that he still had for theater as mad improvisation and fun.

“I abide in good-natured despair about the failure of the ideals of the 60’s revolution,” Patrick posted on his blog a decade before his death. Yet, ironically, the three plays for which he’ll probably be best remembered all deal in some way with the recognition that the political idealism and raw creative energy of the 1960s were impossible to sustain. Both The Haunted Host (1964) and T-Shirts (1979) deal with the clash between a middle-aged playwright who eschews renown and has willingly sacrificed traditional creature comforts for the benefit of his art, and a young, handsome up-and-comer who hungers for the trappings of success as depicted in Life or People magazines. Patrick points out that Jay, the playwright in Haunted Host, is the first “queer with pride” to appear on the American stage, coming four years before the commercially more successful Boys in the Band (1968). In T-Shirts, an older pair of gay men entertain themselves with outrageous banter and wit, while the young man who visits them looks to TV for social validation and narcissistically associates physical beauty with success. It seems the hippie æsthetic of the ’60s has been replaced by the carefully coiffed and blow-dried look of the ’70s.

Patrick’s one commercial success, Kennedy’s Children (1976), is a heartfelt elegy for what was lost after the ’60s. Set in a bar in which the denizens have no social contact with one another or with anyone else, Patrick’s six characters deliver through interior monologues haunting recollections of what the world seemed on the verge of becoming just a decade earlier, and their disappointment with life in the present. “We were building our own counter-culture. It looked as if, maybe, at last, right here on this planet, and right in our own lifetime—civilization had finally begun,” one character recalls. But “the seventies are just the garbage of the sixties!”

Maybe American theater did not want to be saved.

Raymond-Jean Frontain’s most recent book is Conversations with Terrence McNally.