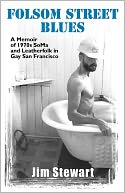

Folsom Street Blues: A Memoir of 1970s SoMa

Folsom Street Blues: A Memoir of 1970s SoMa

and Leatherfolk in Gay San Francisco

by Jim Stewart

Palm Drive Publishing

213 pages, $14.95

SAN FRANCISCO’S South of Market, or SoMa, is a large swath of several blocks that runs parallel to the city’s main thoroughfare, Market Street, much of it in the shadow of downtown and the financial district, and ending somewhere near the Bay Bridge, just a few blocks from the waterfront. No one really agrees on SoMa’s exact boundaries, but few dispute its unique position in gay history. The word “neighborhood” doesn’t quite apply, even in light of longstanding redevelopment efforts and more recent tech-industry-fueled gentrification.

The 1906 earthquake and fire completely destroyed the area, and the blocks of mostly industrial buildings that sprang up there in the first half of the 20th century gave it a gritty, blue-collar feel. In contrast to the hillier (and prettier) streets in most of the rest of the city, SoMa’s streets are broad, straight, and atypically flat, and its residences (mostly apartment buildings) seem outnumbered by warehouses, garages, auto repair shops, and similar businesses.

When gay men began moving to San Francisco after World War II, the unpolished, architecturally nondescript SoMa offered them cheap rents and an alternative to the city’s more residential gay enclaves. It was largely deserted at night, so the gay leather community soon established a community of bars, bathhouses, and active urban cruising grounds. From the early 1960’s to the early 80’s, SoMa was a kind of haven for those who preferred a more hard-edged lifestyle. AIDS, of course, changed all that.

If Market is San Francisco’s Main Street, then Folsom Street is the heart of SoMa. (The annual Folsom Street Fair, which began as a relatively small affair in 1984, is now a major BDSM event, drawing some 400,000 visitors annually from all over the world.) When Jim Stewart, the author of this new memoir, moved to the South of Market area in 1976, it was in its gay heyday. In those days, before the designation “SoMa” was widely used, it was one of San Francisco’s three main gay neighborhoods, the other two being the Polk Street area, just north and slightly to the west of SoMa, and the Castro, farther west.

Like many others, Stewart ended up in SoMa because of its affordability. He found a flat in a run-down building on Clementina Street and agreed to fix it up in exchange for low rent. His carpentry skills enabled him to do much of the work on his own (skills that also helped him earn a living doing work for SoMa businesses). He also used part of the flat as a studio to launch his career as a leather-fetish photographer (the book includes several of his photos). And of course, his flat was the site of many hookups, some more impromptu than others.

Stewart positions his memoir as a companion to, among others, Armistead Maupin’s “Tales of the City” series and Patti Smith’s Just Kids (2010), and the book’s cover copy describes his narrative approach by referencing Isherwood’s famous line, “I am a camera.” The comparisons are apt. Stewart’s style is the prose equivalent of the SoMa milieu he describes—unadorned, no-nonsense, straightforward, and at times raw. He is a reporter, capturing (and lamenting the loss of) a time and place long gone.

Though he made his living as a carpenter and photographer, Stewart is a historian and librarian by training, and he brings this sensibility to his memoir. He quite clearly sets out to record, and he resists the temptation to categorize and philosophize, even in situations where other writers might do so. For example, when he writes of meeting President Ford at a fundraiser at the Sir Francis Drake Hotel, he notes the attempt made on Ford’s life during that visit only briefly, and avoids describing the bungled assassination, concentrating instead on a very intense, presidentially inspired hookup that transpires not long after his handshake with the President.

Stewart’s book is novelistic, artfully non-chronological, and it captures its subject matter vividly. Indeed, in his foreword he pointedly assures the reader: “Everything written here really happened.” One soon learns why this assurance is necessary. Stewart is an engaging raconteur, and he has plenty of good yarns to share. In one somewhat phantasmagoric section, he recounts attending, while on hallucinogens, the installation of the Archbishop of San Francisco at St. Mary’s Church. In another passage, he describes a visit to an underground sex club, the Catacombs, at the edge of the city’s Mission District. Making his rounds there one night, he sees an acquaintance, “an ex-monk dwarf [who]slid his thalidomide arms deep into the bowels of willing penitents who floated on a crowded waterbed in the underground chambers. We emerged with Orpheus as the sun came up. San Francisco. 1970s.”

Stewart often invokes time and place in this way to underscore the elegiac quality of his memories. He pays homage to the many SoMa leather bars, bathhouses, and art galleries that are now long gone. He offers up nicely detailed accounts of day-to-day life on Clementina Street, where he could leave his front door unlocked, commune with his colorful neighbors, take photographs, and flirt with the handsome Middle Eastern kid who worked in the corner store down the street. In this admirably concise memoir, he crosses paths with the famous (actor Raymond Burr; photographer Robert Mapplethorpe; and Jack Fritscher’s famed Drummer Salon, for example) and the infamous. His cast of characters includes society types as well as members of the San Francisco leather community, porn industry, and underground art scene. There’s plenty of sex and, sadly, even a murder. Ultimately, Stewart feels enriched for having lived in a place and time that was “a great experiment, one that made life an art form in that once upon a time City by the Bay.”