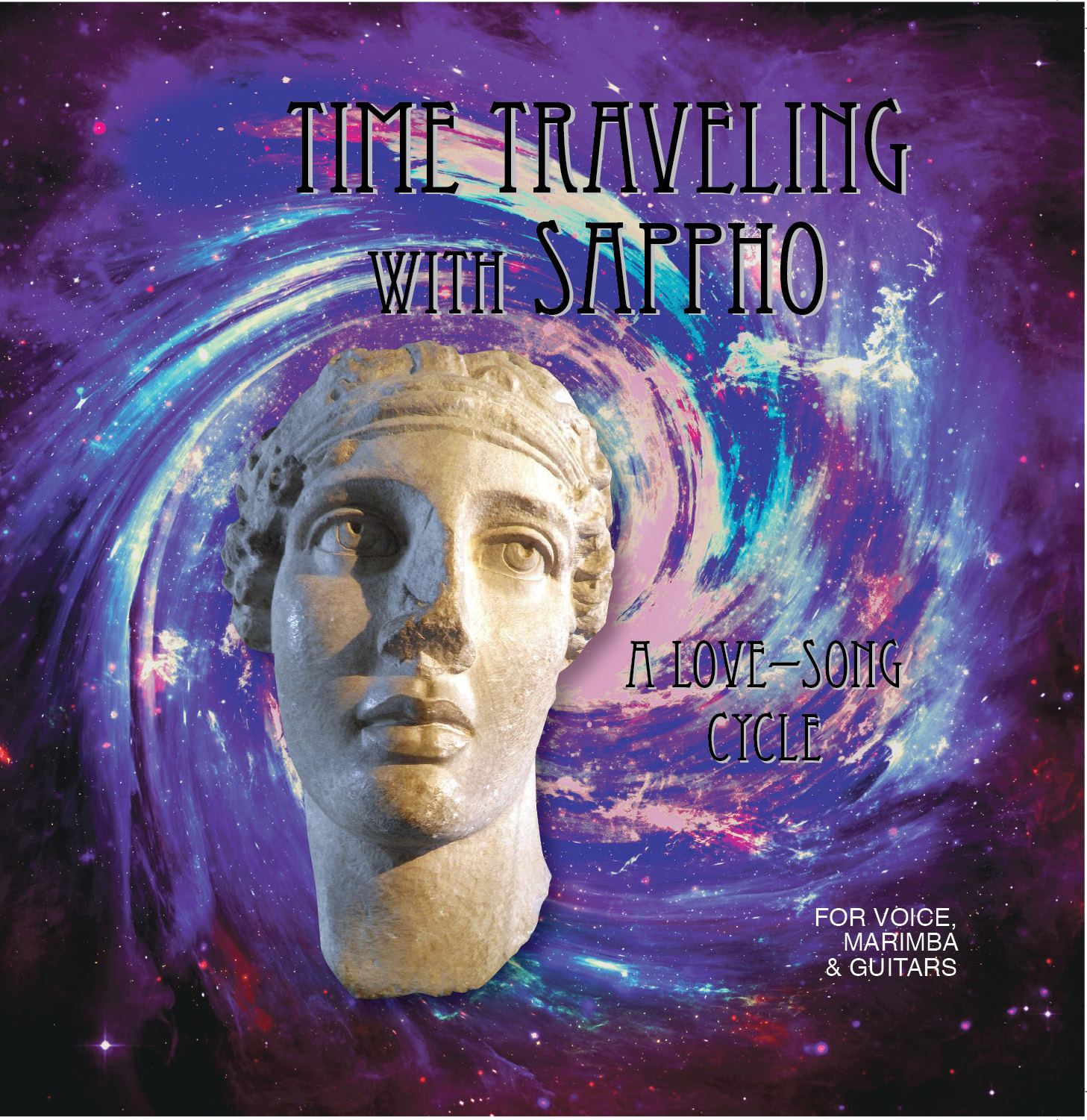

Time Traveling with Sappho: A Love Song Cycle

Time Traveling with Sappho: A Love Song Cycle

Music by Jeri Hilderley

Performed by the SeaWaves

SeaWave Recordings

IT SEEMS everyone’s boarding the Sappho boat these days, eager to travel with the ancient poet and tell the world who she was. One person well qualified to be Sappho’s herald and interpreter is singer, songwriter, and musician Jeri Hilderley, who pays homage to the poet with a stirring new CD, Time Traveling with Sappho. Hilderley co-produced the album with bassist Janet Mayes, who is also her life partner, and with the help of sound engineer Bruce MacPherson.

Sappho lived from the late 7th to the early 6th century BCE in Mytilene, the cosmopolitan capital of the Greek island of Lesbos, directly across a strip of water from the (now Turkish) city of Sardis. Sappho’s passionate poems about the women she loved have been acclaimed since antiquity. Plato, for example, called her “the Tenth Muse.” Sappho sang her poems to music played on the lyre—whence the term “lyric poetry”—and performed at both public and private gatherings, such as goddess festivals and wedding feasts. She’s credited with creating a four-line verse form now known as the Sapphic stanza, and with inventing the plectrum, a thin piece of ivory or tortoiseshell for plucking the lyre’s strings.

Not one of her melodies has survived, but we have about 250 poem fragments, all transcribed from copies made in the centuries after her death. Interestingly, scraps of Sappho’s writing continue to surface. One fragment turned up inside an ancient rubbish heap in the late 19th century, and another was found in 2012, inked on desiccated papyri that may have been recycled as mummy wrappings.

Solid information about the poet’s life is meager. What little is known comes from her poems, from paintings on four Athenian vases, and from what later writers have said about her. Sappho’s poems mention her mother, her three brothers, and a daughter, Cleis, as well as young women with whom she fell in love, including Atthis, Megara, and Telesippa. While both men and women are stirred by her erotically charged poems, Sappho’s words strikingly extol the joys, and lament the disappointments, of lesbian love.

Like Sappho, Hilderley is a city dweller. Born in Midland, Michigan, she studied art and sculpture until coming upon her grandmother’s guitar as a young woman. That discovery marked the beginning of her passion for music. Moving to New York City in the 1960s, Hilderley taught music and writing in the public schools. She became involved in street theater and “happenings” with the man she was married to at the time, and found herself increasingly attracted by the emerging women’s liberation movement. She describes attending a National Organization for Women (NOW) conference in 1970 where radical lesbian feminists calling themselves “the Lavender Menace” (as Betty Friedan had dubbed them) seized the stage to advocate for inclusion. Hilderley soon became involved with the Women’s Music Network and has said that “as I worked with women, I fell in love with them.”

Hilderley was drawn to the percussive quality of the marimba, the playing of which she has compared to sculpting clay. Having started her own music company, SeaWave Recordings, she recorded in the late 1970s a series of love songs based on Sappho’s poems, hand-scoring accompanying music for marimba and acoustic guitar. That song cycle has been fused with another that Hilderley digitally scored and recorded in 2014-15, her voice accompanied this time by acoustic guitar, electric bass, keyboard-generated pan flute, organ, harp, and more. The lyrics are based on a translation of Sappho’s poems by City College classics professor Konstantinos Lardos, and the captivating result is called Time Traveling.

The CD is thus an amalgamation of two recordings by the same artist separated by some 35 years, and the effect is mesmerizing. As you pick up the voice of today’s Hilderley along with that of her younger self, a poignant theme emerges: the passing of time. Sappho herself wrote on this theme, writing: “my skin once soft is wrinkled now,/ my hair once black has turned to white./ … my knees/ that once danced nimbly like fawns cannot carry me.” Sappho also knew that becoming elderly imposes limits on love, as seen in the words poet Anne Carson has translated: “but if you love us/ choose a younger bed/ for I cannot bear/ to live with you when I am/ the older one.”

Time Traveling includes fifteen pieces, and while many instruments can be heard, marimba and acoustic guitar predominate. (The marimba is a set of wooden bars struck with mallets to make low-pitched, resonant sounds.) Hilderley’s two voices, young and old, alternate as they sing words such as: “There can never be one, again, as you.” Several short poems follow, with marimba and guitar growing louder. Suddenly, finger cymbals (keyboard-generated) break in, like small bells, and the singer effuses about her “magnificent rose,” a flower sacred to Aphrodite. Mixing phrases from Sappho with words of her own, strumming her guitar, Hilderley extols the woman she loves.

An emotional high point arrives with the seventh number, as the singer says she has given up being “a wanderer,” because she has found lasting love. Sappho’s amorous words define the mood: “Ah, my sweet one—/ once more to hold you fast./ Once more, my limbs are loosed,/ I tremble to this raging love—/ I, yield.” The singer praises her own lover using words of the most revered female poet, and the effect is remarkable. Brief poems follow, sung with affirmation and joy. At one point, the voices of children at play can be faintly heard, adding a jaunty air. Finally, Hilderley circles back to reprise the opening poem, and quick, intense marimba strokes bring the album to a close.

We may justly ask, is this what Sappho’s performances would have sounded like? Probably not, given the differences between her lyre (a small, hand-held harp, with plucked strings) and today’s marimba and other instruments, not to mention that the poems themselves are compiled from scraps. But it hardly matters. Hilderley and the SeaWaves have “time traveled”—from 1978 to 2015 and from modern times to ancient Greece.

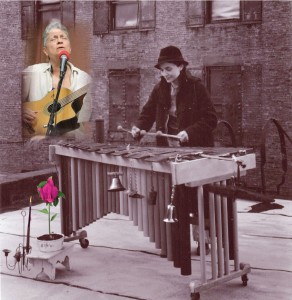

The back cover of the well-illustrated, carefully referenced booklet that comes with the CD evokes this time warp: photographer Eric Lindbloom’s sepia-toned photo shows a young Hilderley, her long brown hair tucked under a felt hat, eyes cast down, striking the keys of a bulky marimba set up in what looks like a New York tenement courtyard. An inset of the gray-haired Hilderley today, eyes closed as she sings, is placed in the upper left-hand corner of the page. This work is a fitting tribute to the musician’s literary muse, Sappho, and to her real-life one, Janet Mayes.

Rosemary Booth is a writer and photographer in Cambridge, Mass.