RECLAIMING TWO-SPIRITS

RECLAIMING TWO-SPIRITS

Sexuality, Spiritual Renewal and Sovereignty in Native America

by Gregory D. Smithers

Beacon Press. 368 pages, $28.99

A SHORT REVIEW of Gregory D. Smithers’ Reclaiming Two-Spirits would report that he presents an LGBT-affirmative history of gender fluid Native Americans and how they had been valued as shaman healers within Indigenous communities. Centuries of European colonization and Christian evangelizing replaced this reverence with homophobia. Since the 1960s, brave LGBT Native activists and artists have battled homophobia within their families and racism in the dominant LGBT movement to reassert their sexuality and culture with its deep spiritual roots in the Two-Spirit tradition among First Nations.

A longer treatment is going to be politically bumpier and conceptually more complicated. The term “Two-Spirit” was only adopted in 1990 at the Third Annual Intertribal Native American/First Nations Gay and Lesbian Conference in Winnipeg, Manitoba. The attendees wanted an alternative to the term “berdache,” which had been applied by Europeans in reference to Native American boys who dressed as girls and performed in sexual rituals. “Berdache” had also been adopted by some gay Natives and anthropologists. The delegates also sought a pan-Indian English term for over 150 words in different Indigenous languages for diverse phenomena involving people whose gender and sexuality (to use Western concepts) shift between female and male. They transition from one gender to another, inhabit an intermediate gender (sometimes called “third sex” or “third gender”), or are fluid in their gender through their lifespan.

Since 1990, the term Two-Spirit itself has come to mean many things.

Most generically, it’s an umbrella term for “gay Indians” or “LGBT Native Americans” (according to the Minnesota Two Spirit Society). More narrowly, the term can be restricted to those who blend male and female spirits and are charged with ritual duties of reconciling these and establishing balance. There have been varied Native critiques of the term. Why choose one English term in place of the hundreds of Native words that are not quite reconcilable? The Navajo word nádleeh suggests fluidity and has been translated as “constant state of change … and nádleehí means one who is in a constant state of change.” The Blackfoot ninauh-oskitsi-pahpyaki can be translated as “manly-hearted woman.” The Cree napêw iskwêwisêhot refers to “a man who dresses as a woman.” A Mescalero Apache man could be Nde’isdzan, a “man-woman.”

Even if we force these different words into Western boxes, they still seem to refer to different Western concepts of cross-dressing, third gender, gender transitioning, gender fluidity, or gender nonbinariness. Anthropologist Alice Kehoe has pointed out that in some Native cultures a person might be the incarnation of more than two ancestor spirits. Thus the term “two spirit” buys into the very bifurcation of gender that it should reject as foreign and colonizing. However, there seems to be general agreement that Two-Spirit is an identity term restricted to Native Americans and should not be appropriated by non-Native New Age LGBT people aspiring to spiritual enlightenment. Ojibwe journalist Mary Annette Pember voiced her anger about the popularization of the term: “My concern is not so much over the use of the words but over the social meme they have generated that has morphed into a cocktail of historical revisionism, wishful thinking, good intentions, and a soupçon of white, entitled appropriation.”

Gregory D. Smithers is acutely aware that he’s stepping into highly contested territory with his sweeping history of Two-Spirit people. In a work that repeatedly claims to be engaged in scholarly decolonization of the history of Native sexuality, he has to acknowledge that he risks being criticized for an act of colonization as a white, Australian, heterosexual, cisgender man. Still, Smithers, a professor of American history at Virginia Commonwealth University, is uniquely qualified for the task, having authored several books on Indigenous history and being proficient in Cherokee. Written Cherokee, a syllabary developed in the 1820s by Sequoyah, was the first Native North American language to have a written form. The lack of Indigenous written records is a core challenge to historians of the First Nations north of the Rio Grande (whereas a number of Mesoamerican civilizations, notably the Olmecs, Mayans, and Mixtecs, had writing). We are dependent on the accounts of European explorers, colonizers, and missionaries or the transcribed oral accounts of Natives who cooperated with them. What credence can we lend these texts, often by writers completely ignorant of and hostile to the cultures they were “discovering”?

Smithers’ work is broadly divided in two parts. First, he engages in a “decolonizing” examination of these early European accounts (largely through translations of the originals and contemporary scholars’ publications about them) and two centuries of anthropological research, also by non-Native (but presumably better intentioned) academics. Second, Smithers weaves together his own extensive archival research on, and interviews with, contemporary LGBT Native American activists and artists, tracing the reinvention of Two-Spirit identity. And reinvention it is. As noted above, many Natives are uneasy that there exists a monolithic “Two-Spirit” shamanistic phenomenon. What does seem startlingly clear is that, in hundreds of Europeans’ accounts, the colonists discovered some form of gender-bending individuals or behaviors. If this wasn’t described in every Native community, historian David Greenberg opined, it’s only because researchers haven’t gone deeply enough. These practices, however, were almost universally condemned and stigmatized as forms of sodomy, “infamous vice,” savagery, pederasty, immorality, eunuchism, and hermaphroditism. Generally, this justified the “civilizing mission,” forced conversion, or brutal elimination of Indigenous practices and people.

These scandalous reports date from the earliest encounters. Christopher Columbus’ doctor, Diego Alvarez Chanca, in a letter of 1494 describes how Carib Natives captured young boys from enemy islands, “cut off their member, and served themselves of them [sexually]until adulthood, and then sacrifice and eat them during festivals.” One of the terms frequently used by explorers to describe these diverse people was “berdache.” As noted, the term “Two-Spirit” was coined in part to replace this disfavored term, which was still used by scholars and Natives until the 1990s. It was first used by 18th-century French explorers, perhaps alluding to the medieval European and Arab terms bardaje or bardadj, referring to effeminate or cross-dressing boys sold into slavery and prostitution. Historian Richard Trexler in Sex and Conquest (1995)—a scholarly exploration of the original language accounts of the conquest of the Americas—takes these pan-continental texts as describing diverse Native institutions of enforced regendering, cross-tribal enslavement, and sexualized political order.

Smithers dismisses such interpretations of European accounts as uncritical of the colonizing, racist, and homophobic prejudice of the conquerors. His alternative, decolonizing reading of these accounts holds that they prejudicially document the diverse First Nations’ appreciation of gender fluid members, and their elevation to special, ceremonial roles as intercessors between genders and/or spiritual domains. He switches with a bit too much facility between accounts spanning centuries and continents to make the case for a unified Two-Spirit phenomenon, which Smithers repeatedly equates with “gender fluidity.” However, he has to acknowledge that the different Native words for natal boys or girls who cross-dress or take on special roles refer to different cultural crystallizations of gender and sexuality. Some Native cultures (like Suquamish) do not have a word, or it has been lost (along with many First Nation languages). Even through the eyes of Christian conquerers, these practices are quite diverse: some Two-Spirits are indeed healers or priests, but some simply have cross-gender occupations (e.g., male basket weaver or warrior woman). Nevertheless, the individual accounts, whether from translations or recent scholarship on particular First Nations, are fascinating and make it clear that the gender / sexuality spectrum is not a 21st-century Western phenomenon.

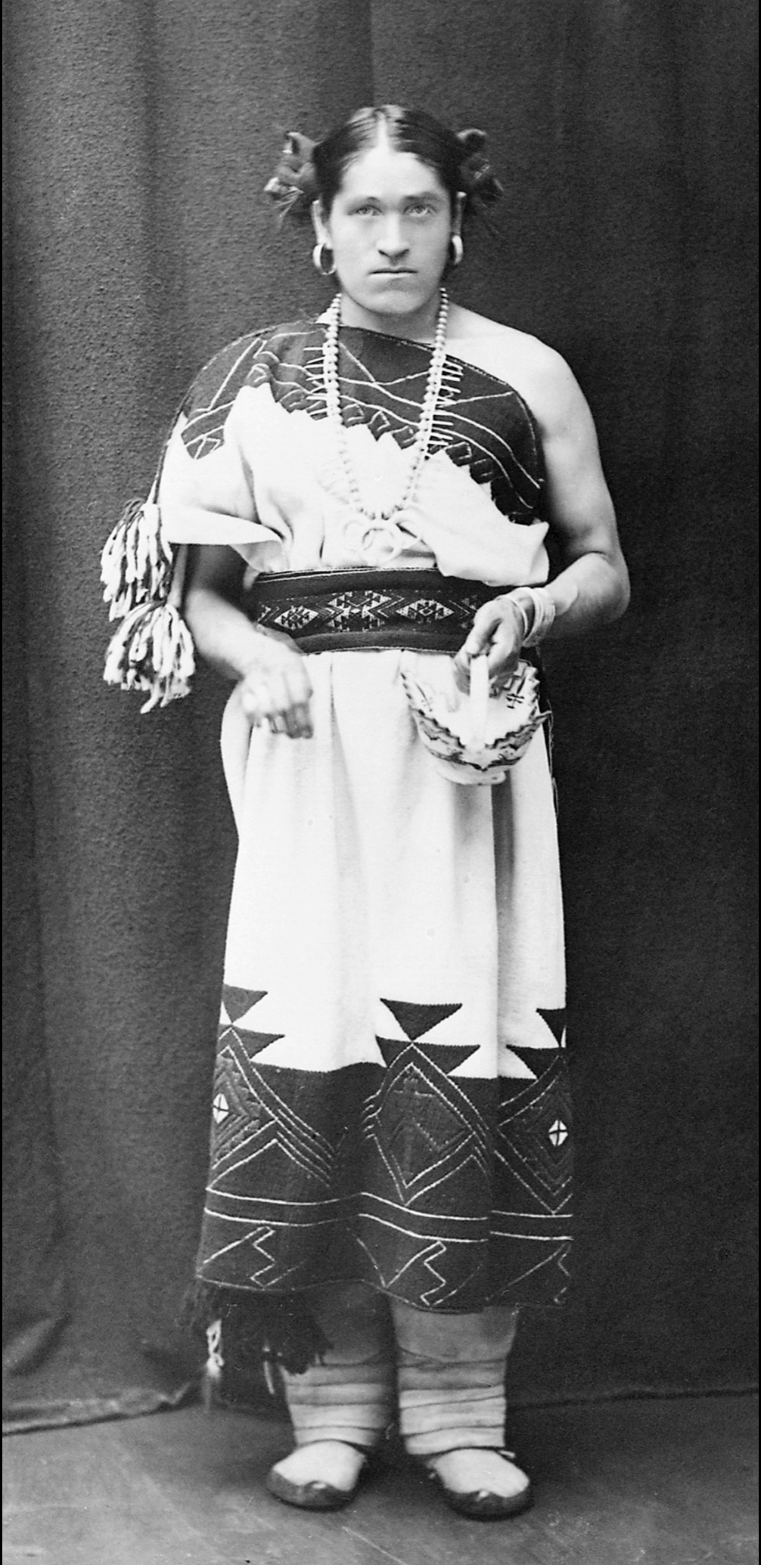

John K. Hillers photograph. Smithsonian Inst.

WeWha (1849-1896) is one of the best documented lha’mana. Will Roscoe, a non-Native independent scholar, drew interest to her story in The Zuni Man-Woman (1991). Dubbed by the press as a “Zuni princess,” WeWha was a natal boy who had been initiated in early childhood into the lha’mana role. Matilda Coxe Stevenson, an anthropologist with the Smithsonian Institution’s Bureau of American Ethnology, brought WeWha on a tour to Washington in 1885, where she displayed her weaving skills and was introduced to dignitaries, including President Grover Cleveland. WeWha was apparently a clever diplomat as well, as she convinced the President to replace the Mexican Indian agent with an American one more sympathetic to the Zuni.

Shifting to his interviews with contemporary LGBT Natives, Smithers richly documents the emergence of lesbian and gay Native activism since the 1970s. Barbara May Cameron (Hunkpapa Lakota) and Randy Burns (Northern Paiute) receive well-deserved attention as founders, in 1975, of Gay American Indians (GAI) in San Francisco. These and other early activists were inspired by feminist and gay rights politics, but also had to contend with racism within those broader movements. The AIDS crisis formed an important backdrop, as Native activists contended with homophobia to develop AIDS education and care tailored to their First Nation communities that were all too eager to consider homosexuality as foreign to Indian Country. Another challenge is overcoming resistance to same-sex marriage in some Indian tribes’ laws (independent of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2015 decision in favor of same-sex unions). Some tribal leaders insist on the foreignness of same-sex marriage and uphold conservative Christian values instead. Some tribes, such as Navajo Nation, have passed specific laws prohibing same-sex marriage in tribal courts.

Aside from thoughtful accounts of Native LBGT+2S activists, Smithers delves into the papers of Harry Hay at the San Francisco Public Library. Hay is widely praised as a labor activist and cofounder, in 1950, of the Mattachine Society, an early “homophile” rights organization. Decades later, Hay and several friends founded the Radical Faeries, an eclectic hybrid of the 1960s sexual revolution, leftist counterculturalism, and neo-pagan spirituality. Smithers carefully traces Hay’s romanticized appropriation of Native culture and spirituality in creating Faerie “origin” mythologies and rituals. For Hay, the berdaches were just one branch of an ancient tree of gender-crossing shaman healer-priests who were being reinvented through the Radical Faeries. Will Roscoe attended the first Faerie meeting in 1979, and his enduring interest in gay Natives and spirituality would lead to his collaboration with the GAI History Project. Roscoe and Randy Burns collected oral histories, short stories, and poems, which were published as Living the Spirit: A Gay American Indian Anthology (1988). It was a moving coming out anthology similar to others of the time with intersectional identities as sexual and ethnic minorities. Its Native writers were still using the term “berdache” in reference to gay Indians, yet were creatively generating a positive history of LGBT in Indigenous America—bringing us full circle to the 1990 birth of “Two-Spirit.”

Smithers sometimes lapses into romanticizing Natives as he criticizes Hay and other non-Native spiritualists and scholars, including 19th-century anthro- pologists engaged in “ethnographic salvage” work of Indian culture. For example, he claims that under traditional matrilineal education, “all Cherokee children received love, care, and guidance.” All? Yet he does passingly acknowledge that Native tribes fought each other, engaged in slavery of women and children, and in some documented cases ridiculed and persecuted gender nonconforming members. As a non-Native writer, he has to be extra cautious. Nevertheless, he presents a carefully documented work in tune with the tremendous resilience, creativity, and community-building of LGBT Native Americans in overcoming centuries of European persecution, misinterpretation, and appropriation of Indigeous cultures in general and Native sexual and gender diversity in particular.

Vernon Rosario is a historian of science and an Associate Professor of Psychiatry at UCLA.