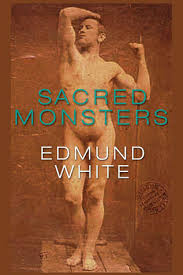

Sacred Monsters

Sacred Monsters

by Edmund White

Magnus Books

256 pages, $24.95

IN HIS INTRODUCTION to Edmund White’s 1994 essay collection, The Burning Library, David Bergman wrote: “As an essayist, White is at his best when he brings to his subject a kind of novelistic color and texture. … [H]is best pieces rely as much on atmosphere as on facts.” While such a description of White’s essays is certainly accurate, I would hesitate to define them solely through the lens of his fiction. In White’s most recent collection, Sacred Monsters, we have another occasion to consider White’s essays on their own terms, and in so doing to consider writing long ignored in the tradition of gay and lesbian writing: the essay.

While most of the essays in this new collection have been published elsewhere (mostly in The New York Review of Books, to which White is a regular contributor), they remind us how erudite and fluid White the essayist can be as he moves between history, experience, and reflection. The collection’s title comes from the French word monstre sacré, referring to cultural celebrities who rise above criticism, who stand on a pedestal beyond our judgment. As such, these essays are not critical interrogations (as the literary scholar may define it), but rather appreciations of these writers and artists that attempt, in White’s words, to put them “into an artistic landscape,” examining their work through their biographies—and, as White so often asks us to consider, through the sexual and emotional lives of these individuals.