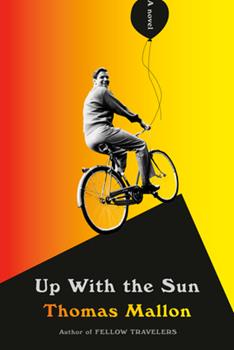

IF YOU DON’T KNOW who Dick Kallman was, you aren’t alone. He’d be a stumper as a Jeopardy! or Trivial Pursuit question. You can discover this has-been (never-was?) minor celebrity in a new novel on his tumultuous life, Up With the Sun, by Thomas Mallon, a prominent writer of gay historical fiction. Mallon has resurrected Kallman from the almost dead; and indeed, how he died is perhaps his biggest claim to fame. On February 22, 1980, he and his male lover were shot to death by three intruders in their tony Manhattan townhouse, in a robbery of their antiques business gone awry.

Kallman’s acting career, the events leading up to this sensational homicide, and the aftermath, including the killer’s trial, form the bases for Mallon’s novel, which is part show-business history, part crime mystery, and part love story covering a thirty-year period spanning the pre-Stonewall era to the early AIDS epidemic. Gossipy and entertaining, featuring appearances from authentic Broadway and Hollywood stars, the novel is a moral dissection of a closeted gay life and a psyche distorted by ambition.

Born in 1933, Kallman’s wealthy father owned the Balsams Grand Resort Hotel in New Hampshire and the Savoy-Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. His mother, Zara, was a minor opera and Broadway actress. She pushed Dick into performing for the kinds of people who stayed at their hotels. His first success was a supporting performance in the Broadway musical Seventeen, which won him 1951’s Theatre World Award as “Most Promising Newcomer.” During this stint, he became infatuated with lead star Kenneth Nelson, even giving him a small diamond pin (which will later hold clues to the motive behind his demise), which Nelson rebuffed, mainly because he didn’t like Kallman, who never got over this rejection. It was a crush that would morph into a lifelong obsession. Nelson is best known to LGBT audiences as the acerbic Michael in the off-Broadway play The Boys in the Band. Years later, he was the warmup act for singer-actress Sophie Tucker in Las Vegas.

Back to Kallman: he became part of Lucille Ball’s comedy troupe workshop in the late 1950s. He toured the country as the lead in the musical How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying. In the 1965-’66 TV season, he starred in the sitcom Hank as a charming con artist who insinuates his way into a local college, sometimes impersonating absent students, in order to take classes, pick up some illicit credits, and (he hopes) earn a college degree. Poor ratings and reviews ended the series after one season. This was the zenith of his acting career.

Back to Kallman: he became part of Lucille Ball’s comedy troupe workshop in the late 1950s. He toured the country as the lead in the musical How To Succeed In Business Without Really Trying. In the 1965-’66 TV season, he starred in the sitcom Hank as a charming con artist who insinuates his way into a local college, sometimes impersonating absent students, in order to take classes, pick up some illicit credits, and (he hopes) earn a college degree. Poor ratings and reviews ended the series after one season. This was the zenith of his acting career.

A short-lived national tour in a musical show, a few unsuccessful albums of pop standards, and sporadic appearances on comedy and drama series led to Kallman’s disenchantment with show business and his “retirement” in the early 1970s. Making use of his business acumen, he founded, with actress Dolores Gray, an antique business named Possessions of Provenance. Despite a few ethical lapses on Kallman’s part, the business prospered. At this time he met Steven Szladek, a graduate student two years his junior, who became both his partner and his business assistant. These chapters are narrated by an omniscient voice who offers flashbacks of Kallman’s career.

In alternating chapters, the first-person narrator is Matt Liannetto, a piano accompanist who met Kallman when he starred in Seventeen way back in 1951 and who meets up with him sporadically for the rest of his life. He’s the sweet-natured foil to Kallman, but he also has serious reservations: “I’m sorry I can’t write more about Dick. I disliked him for all the obvious reasons that most people did.” He had dinner at Kallman’s apartment the night that he and Steven were killed. He later identified, through a vocal lineup, one of the murder suspects. He became romantically involved with Devin Arroyo, a former hustler, who worked as a clerk at the police department. Through Matt, we get details of the criminal investigation and trial of the three killers, who were eventually convicted, an account that is only intermittently intriguing.

On stage, Kallman had an amiable personality and a pleasant singing voice, but in private he was reputed to be nasty, self-serving, and obsequious, deploying embarrassingly false flattery that came across as phoniness. Mostly in the closet but still pegged as gay in the industry, he wore flamboyant clothes and called other gay men “pansies” to demean them and to imply that he wasn’t one of them. He sometimes dated women as “beards,” such as former child actress Margaret O’Brien, to disguise his homosexuality.

He smashed actress Dyan Cannon’s finger while touring in How To Succeed, because he thought she was upstaging him. Years later, at the Golden Globes Awards, she screamed at him: “You sick bastard.” Mallon writes of Kallman that “ambition stuck out like a cowlick or a horn.” Mallon manages to create empathy for his subject, though, so we take pity on him as his own worst enemy. Mallon is adept at recreating the showbiz aura and the “anything goes” atmosphere of the late ’50s to the mid-’60s, as well as the trials and accommodations needed to survive being gay in that milieu. Mallon suggests that Kallman’s deep need for love, which he never found, contributed to his aggressive, ingratiating personality.

One revealing incident hinted at how damaging homophobia could be. When Kallman attended the legendary 1961 Judy Garland concert at Carnegie Hall, Mallon writes about the mostly gay audience: “Whatever was broken in these guys was reaching toward and sparking whatever was broken in her … in him [Kallman] there had been something broken, but whatever it was had been soldered over, annealed in a way that left it unreaching and unreachable.”

Mallon’s investigation of Kallman reads like an autopsy, even though the reader is warned that his story “is inspired by actual events considerably altered by the author’s imagination.” Yet there’s an authenticity that’s both frightening and compelling. Mallon has pierced the heart of darkness at the root of Kallman’s soul. Kallman might deserve to be forgotten, but Mallon’s portrait of a sad thwarted tragic talent as a sour parable on ambition is unforgettable.

Brian Bromberger is a freelance writer who works as a staff reporter and arts critic for The Bay Area Reporter.