The Boys in the Band

A Play by Mart Crowley

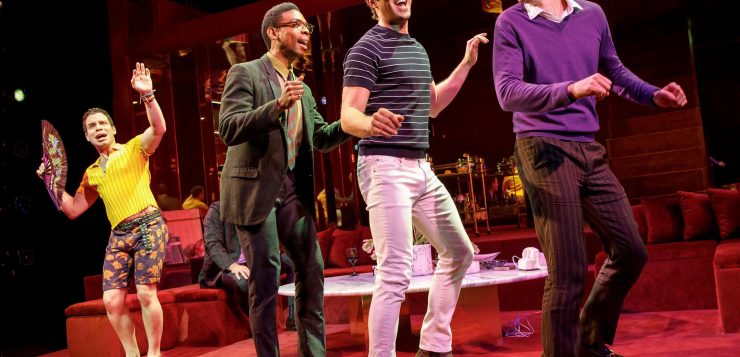

Directed by Joe Mantello

IT WAS EITHER kismet or dumb luck that the original production of The Boys in the Band appeared Off-Broadway in 1968, the year before the Stonewall Riots. Everyone of note seemed to be pulling up in his or her limo to watch a group of Manhattanite gay men throw a birthday party for one of their own. People were drawn in surprising numbers by the fast-paced repartee, the transgressive language, and the certainty that one was in for a slice of tribal anthropology, only a hell of a lot funnier. Straight people went to it no doubt hoping to learn the secret of why those gay boys were so damn funny.

In the aftermath of Stonewall, The Boys in the Band was accused of being an example of a retrograde representation of gay life. Self-pity and guilt over one’s gayness were out of fashion, while coming out of the closet was in. Now, fifty years later, we have the first Broadway production of Mart Crowley’s play, and some may ask: do we need to go back there? For what purpose?

The simple answer might be that a community that forgets its past stands on shaky ground in the present. Those of a certain age may find these memories painful, but I think we need to be reminded of where we came from. I will admit to some skepticism going into the play, but under Joe Mantello’s skilled direction, and presenting the piece at a taut ninety minutes without intermission, this production moves at breakneck speed. Also, we’re treated to a cast of out actors who take the material and run with it.

Does Boys in the Band stand in for all gay life in the year 1968? No, but it gives us a slice of gay life occupying the corridors of Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Greenwich Village, and possibly even the somewhat shabbier bourgeois precincts of the Upper West Side. Not that we see any of this, but the aspirational young urban gay men who populate the stage in the swanky duplex apartment of Michael (played by Jim Parsons of The Big Bang Theory), the evening’s host, suggest a queer cohort from around the city. None appears to be leading a life of quiet desperation: they are too vocal in their neuroses for that, too self-deprecating and ironic, only too aware that they are part of a despised minority. Nevertheless, they take their lives in hand in the embrace of their gay brothers.

Crowley’s play is a well-oiled machine broken up into roughly three acts that move seamlessly from comic exposition to dramatic climax to diminuendo before the final curtain. The setup is uncomplicated: Michael is preparing a birthday gathering for Harold (Zachary Quinto). Before the guests gather, described mostly as Harold’s friends, Michael’s weekend housemate, Donald (Matt Bomer)—a past pick-up who has turned into a fast friend and sometime fuck-buddy—arrives direct from the Hamptons. In their shared opening scene, we learn that both are classic neurotics thick into therapy. Furthermore, Michael, increasingly aware that the hairs on his head are thinning and his tolerance for late-night binges is waning, admits that he’s been on the wagon. He’s also stopped smoking. It’s been five weeks; Donald admires the effort. He can always tell when Michael is drinking: his hostility begins to show.

One by one, the guests arrive, a demographic of the era’s gay stereotypes. There’s the effeminate Emory (Robin de Jesús), life-of-the-party with “her” unapologetic fairy manners and waspish tongue (“Who do you have to fuck to get a drink around here?”). Emory has brought with him Harold’s gift, a young, hunky hustler known only as “Cowboy” (Charlie Carver). Next come Larry and Hank (Andrew Rannells, Tuc Watkins), a couple of apparent opposites—the former happy and on the sexual merry-go-round; the latter a divorced man with children seeking to recreate the stability of conjugal fealty. And there’s Bernard (Michael Benjamin Washington), the lone African-American guest, a studious-looking “Good Negro” who puts up with Emory’s ironic racial putdowns.

The play’s real motor involves the presence of one outsider, Alan (Brian Hutchison), Michael’s hidebound former college roommate who suddenly needs the company of his reliable New York school friend. Alan is in crisis, apparently involving his wife Fran and a turning point in their marriage. Michael has never admitted his homosexuality to his old college chum, straight-arrow Alan, and he doesn’t want anyone letting the cat out of the closet. Recognizing that Alan, in rare emotional turmoil, isn’t going to disappear, Michael anxiously tries to regulate everyone’s behavior and language.

The setup is complete. Alan walks in only to discover several men in a line dance, hooting and hollering in raucous abandon. Uh-oh. While the boys in this band try to cover, Emory will have none of it. His argot is High Camp; no male is not a “she.” No sooner has the Waspy Alan established a budding rapport with Hank, who is as “straight appearing” as they come, than Alan, sensing the tensions in the room and his presence as an awkward intrusion, begins his farewells. But one too many sallies from queeny Emory, who admits he has “such a problem with pronouns,” punctures Alan’s reserve. “How many esses are there in the word pronouns?” he shoots back. Emory rises to the bait: “How’d you like to kiss my ass—that’s got two or more esses in it!” Now Alan answers the challenge: “How’d you like to blow me!” In high dudgeon, Emory quickly offers his indelible riposte: “What’s the matter with your wife, she got lockjaw?”

Mayhem ensues as Alan lunges at Emory, calling him “queer,” a “cocksucker,” a “mincing little swish,” and a “goddamned freak,” all the while bloodying his nose. Hank pulls Alan off the screaming Emory as Bernard ministers to Her Majesty’s wounds. Ding-dong. Someone’s at the door. Enter Harold, the birthday boy, who’s late to his own party and immediately sees that he has missed a moment of high drama, what with Emory bleeding and sniveling on the floor and this unknown man in the house.

In the aftermath of this disastrous display for the guest of honor, Michael’s composure is shattered. Director Joe Mantello engages a bit of tried-and-true stagecraft to make sure we don’t miss the point. Lights dim on all the guests, who freeze in place. Suddenly, Michael appears in a spotlight as the others recede into darkness. He pours himself a drink and downs it. Within minutes, “hostility” spews as Michael chastises birthday boy Harold: “You’re stoned and you’re late! You were supposed to arrive at this location at approximately eight-thirty dash nine o’clock!”

Tall and imposing, Harold, whose self-regard and theatrical bearing were established when he first entered and slithered out of his trench coat, will not be shamed: “What I am, Michael, is a thirty-two year old, ugly, pockmarked Jew fairy—and if it takes me a while to pull myself together and if I smoke a little grass before I can get up the nerve to show this face to the world, it’s nobody’s goddamn business but my own.” Harold has laid down the challenge. And now the games really begin.

Let’s avoid spoiler alerts. Suffice it to say that Michael, having lost all control of the party, re-imposes his will by forcing everyone to play a variant of the game of “Truth.” Here, each person must telephone someone he has always secretly loved and confess that love to him. Michael has devised an elaborate point system; and so it begins. In a climactic scene that pits the domineering Michael against the imperious Harold, Quinto reveals himself a masterful character actor playing a man whose entire life is a performance: Harold condescends to share the planet with us. Jim Parsons as Michael must reveal a lifetime’s insecurity and self-loathing under his armored exterior of bitter camp irony. As the play’s central antagonists, their verbal sparring is a thrill to behold.

The Boys in the Band may be a period piece, but it has been given fresh life with an ensemble cast that has been put through their paces by one of Broadway’s premier directors, Joe Mantello. Directorial choices Mantello has made, especially at the play’s denouement, restore dignity to crucial characters and balance to the evening’s eruptions—a feature which may not have been so clear in the aftermath of Stonewall, when the play would already have been seen as wallowing in self-pity instead of demanding equal rights. To be sure, these “boys” were not the first ones to march for liberation, but it helps make vivid why others did.

Allen Ellenzweig, a frequent contributor to these pages, is a writer based in New York City.