The Man Who Loved Birds

The Man Who Loved Birds

Fenton Johnson

Univ. Press of Kentucky. 328 pages, $24.95

Brother Flavian, after seventeen years in a Kentucky monastery—which he entered to escape the draft—wanders into the local tavern, beginning a series of encounters with the surrounding county. This not-very-holy fool’s excursions flush out such indelible characters as Meena, a Bengali doctor whose guardedness in a strange land protects her only so far. Most winning and revelatory is Johnny Faye. Illiterate yet unwittingly intelligent, a ne’er-do-well who’s acutely attuned to nature, he merges with the land itself. Johnny Faye pulls Flavian every which way, creating human comedy at its most ennobling. Redeeming the cliché of the Vietnam War vet (and marijuana cultivator), every interaction surprises us. He is a seer, unlike the timid monk, and opens up to everyone he encounters. Even his deadly struggle with county attorney Harry Vetch pits playful masculinity against its destructive kin.

The story trusts its place and people. Fecund humanity, the heavy burden of the expected, and the glory of the unexpected allows these characters to change constantly, even via lovemaking. As in his earlier novel, Scissors, Paper, Rock (re-issued by University Press of Kentucky), Johnson reveals sexuality through a character’s awareness, not the heavy hand of the author’s desires. The male-to-male sexuality is erotically and emotionally textured—acts of what might be called agape. Johnson’s nonfiction work (Geography of the Heart, Keeping Faith) examines grief and loss and the conflict between faith and belief. In this novel he pulls us into vivid and messy lives, rich with revelatory humanity.

Jeff McMahon

Gay American Novels, 1870-–1970: A Reader’s Guide

Gay American Novels, 1870-–1970: A Reader’s Guide

by Drewey Wayne Gunn

McFarland. 200 pages, $39.95

What differentiates Gay American Novels from so many other compendia of long-forgotten novels that have been published over the past couple of decades? Author Drewey Wayne Gunn says that 75 of the 257 books profiled have not appeared in any other bibliography, and he does not dismiss a book for being too lowbrow or too highbrow. Tracing the development of gay male identity—not queer identity, nor proto-gay identity, he’s clear to point out—is his concern, and he’s “interested in novels in which sexual desire is unmistakably a key component.”

Entries are arranged in chronological order from Bayard Taylor’s Joseph and his Friend (1870) to Gerald Walker’s Cruising (1970) and Donald E. Westlake’s A Jade in Aries (1970)—both murder mysteries in which “the victims are homosexual and the killers are closet cases.” There are quite a few big names: Christopher Isherwood, John Rechy, Samuel R. Delany, William S. Burroughs. In his description of Distinguished Air, by Robert McAlmon (1925), Gunn states that McAlmon had been in love with Gore Vidal’s father, and notes the many friends of McAlmon, such as painter Marsden Hartley, who appeared in his novels. Gunn also speculates that McAlmon may have written under the name of Robert Scully, author of Scarlet Pansy (1933). Several works of the Harlem Renaissance are represented, among them Blair Niles’s Strange Brother (1931), Claude McKay’s Home to Harlem (1928), and Wallace Thurman’s Infants of the Spring (1932). It’s notable that Niles was a straight married woman. Richard Amory’s Song of the Loon (1966) is represented, as is the cleverly titled parody Fruit of the Loon (by “Ricardo Armoury,” 1968). Despite its overlap with other collections, the reader who is looking to mine the early gay literature will find a fair number of gems in Gay American Novels.

Maurice Gold

The Argonauts

The Argonauts

by Maggie Nelson

Graywolf. 160 pages, $15.

Maggie Nelson cements a well-deserved reputation as one of the best nonfiction writers of her generation with The Argonauts, which has just been published in the UK but has been garnering significant acclaim, and fans, in the U.S. for over a year. It’s a daring, intelligent, strange, and beautiful book. It collides barely-there glimpses of rough sex in shower stalls against dialogues with Wittgenstein and Barthes. It’s a very personal book, which occasionally addresses Nelson’s partner, Harry Dodge, directly. (“What’s your pleasure? you asked, then stuck around for an answer.”) Nelson and Dodge have a son together, Iggy. The saga of his conception and birth runs throughout the book, slaloming between several others themes, including Dodge’s gender transition (he identifies as “a butch on T”) and Nelson’s relationship with the “many gendered-mothers of [her]heart”—her intellectual influences and mentors, among them Eve Sedgwick and D. W. Winnicott.

Nelson cribs her title from Barthes, who compares “the subject who utters the phrase ‘I love you’” to a sailor on the Argo, who might cycle out old parts and replace them with new ones but still calls his ship by the same name. Many things we may think are solid are in fact “argonautical,” Nelson implies: bodies, minds, political movements, genders, selves. Even as Nelson struggles with how language constantly replaces, and attempts to represent, experience (“How can the words not be good enough?”) she has created an essential thing, a guide to the first years of the queer 21st century, and a hymn to love in all its forms.

CJ Byrd

Communal Nude: Collected Essays

Communal Nude: Collected Essays

by Robert Glück

Semiotext(e). 392 pages, $18.95

This remarkable book confirms what Robert Glück’s devoted readers have long known. He is one of our smartest, most sympathetic—and underrated—cultural commentators on GLBT issues and æsthetics. This fact has been further illustrated by a career of fiction writing over four decades, resulting in many must-read titles, including the novels Jack the Modernist (1985) and Margery Kempe (1994), and two era-defining poetry and short story collections: Reader (1989) and Denny Smith (2003).

The Cleveland-born author cofounded the inspirational New Narrative movement in San Francisco in 1979. Many of the pieces collected in Communal Nude reflect upon the ideas of that movement and its important fiction writers, including Kathy Acker, Kevin Killian, Dodie Bellamy, Sam D’Allesandro, and Bruce Boone. New Narrative interprets our storytelling in terms of GLBT identities and self-constructions—and, in turn, considers these latter abstractions in light of fictional, nonfiction, poetic, and visual art works. New Narrative’s most important common thread is its resistance to marketized GLBT identities and its insistence on individual agency, artistic choice, and selective serendipity.

Glück is as much a poet as he is a novelist and an essayist, and the prose found in Communal Nude is anything but prosaic; it soars. Take this excerpt from a 2008 essay titled “Bataille and New Narrative” on the American coming-out novel: “The family was a strangely remote institution in the lives of most gay men. It was like the old country: a way of life, a set of gestures, and even a language that had been left behind. Certainly the ever-radical hippie credo that helped shaped the beginning of the gay movement—that play is more important than work—could not be affirmed in the family context. In a sense, our writers were faced with the problem of finding a public stage on which our actual lives could be portrayed.” Beautiful, still timely, and above all very wise.

Richard Canning

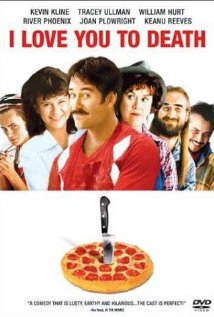

Love You to Death

Love You to Death

by Tegan and Sara

Vapor/Warner Bros. Records

Tegan and Sara Quin are 35-year-old twin sisters from Canada. They’re striving to become the first openly lesbian pop superstars on the planet, and they may well be on their way. The erstwhile folk-rock act debuted in 1999, signed to Neil Young’s label, but never really enjoyed mainstream success until 2012’s Heartthrob, which suddenly landed them on the Top 40. Due to the breakout single “Closer,” the Quins rode the wave of commercial success, even opening for Taylor Swift and Katy Perry. Heartthrob was electropop perfection, comprised of mostly three-minute songs about unrequited love and bad breakups (familiar pop fare). Their eighth album, Love You to Death, isn’t as energized as their last—lyrically clunky, it sounds mostly like a collection of B-sides from Heartthrob—though it does have some hummable hooks, such as “BWU” (Internet slang for “be with you”) and “Boyfriend” (sung from the perspective of a girl tired of being another girl’s secret lover). In a recent interview, Sara Quin praised openly gay acts like Troye Sivan, Years & Years, and Sam Smith, adding: “But it does feel like, ‘Man, can we get some queer ladies up in this joint?’” If Tegan and Sara keep on re-inventing themselves, they could be just the ladies for the job.

Colin Carman