Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997

Writers Who Love Too Much: New Narrative 1977-1997

Edited by Dodie Bellamy and Kevin Killian

Nightboat Books. 544 pages, $24.95

Fans of New Narrative (NN) will leap to devour this remarkable anthology, a fortieth-anniversary “Best Of” that sensibly confines itself to the NN phenomenon’s first two decades. Those who don’t know what the San Francisco-based movement is should take its significance on trust, and read this right now! You’ve lots of catching up to do! The movement had its origins in the science fiction-based poetry scenes of the 1970s, but Writers Who Love Too Much shows the extent to which its tentacles reached out to a wide range of non-naturalistic poets, essayists, novelists, and even playwrights across the U.S. and beyond. Key figures include both of this volume’s editors, whose generosity in their introduction is characteristic of all the key NN writers.

While the East Coast publishing matrix became ever more ruthless, corporate, and opportunistic in the ‘80s and ‘90s, including in its promotion of LGBT books as a subgenre, the New Narrators focused on avant-garde collaboration, dialogue, and mutual support (mostly). They did not hope to make money or have a commercial “hit,” and in almost every case they succeeded at commercial failure! The exceptions would include Kathy Acker, whose novel Great Expectations is excerpted here, and her biographer Chris Kraus, whose I Love Dick is also excerpted. Other contributors who “crossed over” include Rebecca Brown, Dennis Cooper, Brad Gooch, Gary Indiana, Eileen Myles, Sarah Schulman, and Lynne Tillman.

Richard Canning

David Bowie Made Me Gay: 100 Years of LGBT Music

David Bowie Made Me Gay: 100 Years of LGBT Music

by Darryl W. Bullock

Overlook Press. 320 pages, $35.

The year 2016 was a mixed bag for music historian Darryl W. Bullock. His book Florence Foster Jenkins made it to the silver screen, with Meryl Streep in yet another Oscar-nominated performance. But another icon, David Bowie, died earlier that year, and out of Bullock’s grief came his latest work, David Bowie Made Me Gay: 100 Years of LGBT Music. The author does not confine himself to the usual suspects—Lou Reed, Melissa Etheridge, George Michael—or even to the past fifty years. Encyclopedic in scope, the book goes back to Marlene Dietrich in Berlin and the pansy revues in 1930s L.A., but also catches up with a Kenyan rapper named Art Attack and the Russian punk trio Pussy Riot of today. Then and now, he observes: “LGBT musicians have powered many of the most important stages in the development of music over the last century.”

The standout chapter is “Lavender Country,” because the gay side of Country and Western is typically overlooked. Bullock stresses how current acts like Chely Wright and Drake Jensen are carrying the torch passed by k. d. lang, among others. The book is dedicated to the victims of the Pulse Nightclub shooting of 2016, where the 49 Floridians slain were largely men and women of color, which makes Bullock’s profiles of black artists like Tony Jackson and Bessie Smith all the more poignant. The book ends with the threat of Trump in the ascendency and artists scrambling to organize fundraisers for causes they fear will come increasingly under attack with the resurgence of Republicanism. Bullock’s time-capsule reminds us that gay politics and rock ‘n’ roll have long been intertwined.

Colin Carman

Sexagon: Muslims, France, and the Sexualization of National Culture

Sexagon: Muslims, France, and the Sexualization of National Culture

by Mehammed Amadeus Mack

Fordham University Press. 344 pages, $27.

If France is shaped like a hexagon, then the study of sexuality in France leads to the word “sexagon.” In this lively study, Mehammed Mack proposes that the French goal of mixité, or assimilation, has been recast in sexual terms following the dramatic increase in Muslim and Arab residents since Algeria gained independence in 1962. Mack, who teaches French and gender studies at Smith College, offers his view of French attitudes toward “others,” defined by ethnicity, religion, gender, or sexual identity. One provocative finding is that immigrants are being pushed to disclose details about their private lives, including their sexual lives, to demonstrate their aptitude for citizenship in today’s France. So, for example, North African immigrants living in Parisian suburbs may resist answering mental health workers’ questions about their family life, because exposure makes them feel vulnerable. LGBT Arabs and Muslims may be even more wary of self-disclosure. However, refusing disclosure has gotten harder in today’s France, because psychologists “pathologize the closet” and often adopt an “imperative of ‘outness’” toward sexual minorities. French newspapers, TV shows, and films criticize LGBT immigrants’ secrecy as well. But Mack found that porn films might be an exception. A porn film may start with an obnoxious cliché—for example, “homo thug” or “the veil as striptease”—but without a requirement to be politically correct. The result may be a largely accurate picture of sexual creativity in Muslim suburbia. Sexagon vividly portrays the context in which many French LGBT immigrants live now, under pressure for self-disclosure.

Rosemary Booth

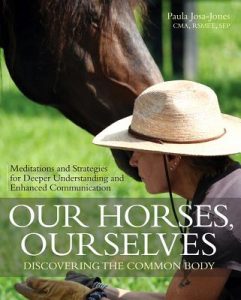

Our Horses, Ourselves: Discovering the Common Body: Meditations and Strategies for Deeper Understanding and Enhanced Communication

Our Horses, Ourselves: Discovering the Common Body: Meditations and Strategies for Deeper Understanding and Enhanced Communication

by Paula Josa-Jones

Trafalgar Square. 278 pages, $29.95

Choreographer and equestrian Paula Josa-Jones has written an intelligently observed, beautifully rendered collection of experiences and inspirations about her interactions with horses. Josa-Jones approaches riding as the dancer she is, calibrating breath, balance, and alignment, while focusing on her core. As important, she reminds us how essential it is to become “one with the horse” through a deeper understanding of how they experience the world: “Always in the moment, aware of smells, sounds, and sights, what is near or far, hard or soft, familiar or strange.” As a choreographer, Josa-Jones created critically acclaimed works featuring dancers and horses. Not dressage events, they are lyrically expressive swatches of movement built from somatic improvisations between humans on the ground and equines cueing off each other. These dances are wonderfully illustrated through gorgeous photographs and choreographic notes. Interviews and teaching from such lesbian luminaries as visual artist Gillian Jagger, composer Pauline Oliveros, and performance artist Ann Carlson further illuminate the author’s journey toward embodied awareness. Josa-Jones’ wife, Pam White, complements the text with explosive, color-saturated paintings. Meditations and exercises encourage the reader to pause, embrace stillness, focus on breath and touch, become more intentional, and embrace interconnectedness.

John R. Killacky