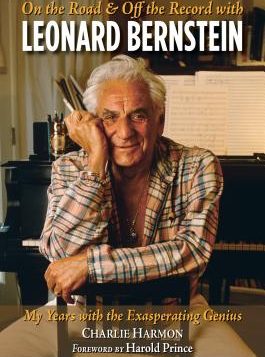

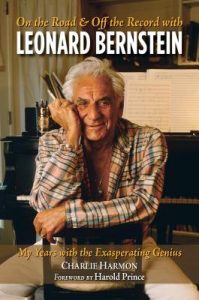

On the Road and Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein:

On the Road and Off the Record with Leonard Bernstein:

My Years with the Exasperating Genius

by Charlie Harmon

Imagine Press. 272 pages, $24.99

In this tell-all book, Charlie Harmon—orchestra librarian, music arranger, and editor—recounts his four exciting, draining years as assistant to Leonard Bernstein. He describes his job as manager of Bernstein’s day-to-day life as a whirligig of phone calls, appointments, music scores, and traveling. But managing Bernstein involved a lot more. The maestro was demanding and prone to “bouts of fury and bratty behavior.” Harmon was given the job of monitoring Lenny’s “celebrated libido” for young men and keeping this information from reaching the press.

Bernstein’s manic behavior was exacerbated by the vast amounts of Dexedrine he consumed and, of course, the alcohol. These frenzied episodes were often followed by major bouts of depression, when Bernstein wouldn’t shave, shower, or sleep for days. Contributing to his frenetic behavior was grief over his wife Felicia’s death in 1978. According to Harmon, Lenny seemed haunted by her. He seemed at times to be pursued by demons—driven to exhaustion by a relentless schedule of conducting, teaching, and composing. He sometimes complained that no one cared about him as a person.

We get a good sense of life with Lenny from 1982 to ’86 through the lens of Charlie Harmon. We travel all over the world with the maestro, and we meet plenty of celebrities along the way. For Harmon, his time with Bernstein was a mixed blessing. He ended up suffering from severe exhaustion and depression. On the other hand, it provided him with an extraordinary education. His four years as assistant to a genius were a self-revelatory journal as well as a musical one.

Irene Javors

At first blush, it is possible to assume that Cassara’s novel is primarily about New York City’s black and Latino ball culture featured in Jennie Livingston’s Paris is Burning (1990) documentary. Both the novel and the film are peppered with extended monologues by drag performer Dorian Corey and the House of Xtravaganza, which Livingston lingers on in the film and which provides Cassara with his characters (Angel, Hector, Venus, and Juanito). But there the similarity ends, as Cassara’s fictionalized account imagines their lives outside of the circuit over a longer timeframe (1976–1993). With this expanded view, we learn about their lives before each character found the camaraderie and shelter provided by Xtravaganza. Incest, rape, abandonment, and drug abuse affect their lives as teens to differing degrees, and new horrors await them during the plague years of 1986 to 1993, which comprise two-thirds of the narrative. Unlike many depictions of gay and transgender suffering, here such trauma is not included for dramatic effect. Rather, through their woe and loss we learn more about the characters who survive and how they cope. Denial, revenge, homecoming, and a renewed commitment to rebuilding communal ties are all projects that Cassara’s characters bravely tackle.

Jayson Morrison

Apocalypse, Darling is a wonderful addition to Barrie Jean Borich’s literary explorations of queer and Midwestern identities. My Lesbian Husband (1999) won her an American Library Association Stonewall Book Award and Body Geographic (2013) was given a Lambda Literary Award in Memoir. In this new memoir, the author draws inspiration from T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. But it might be more apt to see Barrie Jean Borich as a postmodern Willa Cather, what with her exquisitely rendered, humane illuminations of the particulars of place and the multiplicities of family constellations.

The memoir’s organizing event happens when Borich and her “gender-queer male expressive wife” attend the wedding of her estranged father-in-law, who at age 75 reunites with a high school sweetheart. Bewildered extended families on both sides awkwardly comingle. The locale, too, is surreal—an exclusive gated community alongside postindustrial remediated brown fields of Indiana steel mills. Time is ever shifting; painful memories fill in the backstories of relationships with their abusive “hard drinking Michigan Swede” father. Siblings and their spouses wonder why they came. Juxtaposing these passages with pristinely elegant descriptions of the toxic area now reinvented as park land, the author muses: “I want to see if change is possible, if wastelands can revive, if lost love and refound love can coexist, if unloving fathers can become loving, even lovable.”

John R. Killacky

Patient Zero and the Making of the Aids Epidemic

Patient Zero and the Making of the Aids Epidemic

by Richard A. McKay

Univ. of Chicago. 400 pages, $35.

Of the many books on the AIDS epidemic, the one that undoubtedly had the greatest impact was Randy Shilts’ And the Band Played On. In this new book, Richard A. McKay picks up on an important and controversial aspect of Shilts’ book concerning the much-maligned figure, Gaetan Dugas, dubbed “Patient Zero” for his supposed role in introducing HIV into the U.S. Dugas became the de facto monster of the AIDS crisis thanks to Shilts and other reporters. The main question that McKay tackles is why Americans required a “patient zero” at all. Dugas became different things to different groups. Gay men positioned him as a boogeyman, haunting the bath houses, infecting others at random. Straight Americans saw an unapologetically sexual foreigner infiltrating the U.S. with those dirty desires. McKay concludes that Patient Zero provided everyone with a scapegoat and relieved some of the fear caused by the AIDS virus, offering a simplified explanation for those who want “neat, uncomplicated answers.”

McKay has taken a misunderstood monster who appears in the periphery of many essential AIDS-related works and has humanized Dugas as a person caught in the crosshairs of a terrified gay population, a sensationalist media, and an indifferent government. The final section of the book features an oral account from one of Dugas’ paramours who describes him as “no ogre and no saint … just a young man exploring the world as it opened up for him in his twenties.”

Dan Calhoun