Shakespeare’s Tempest ends with Miranda, the daughter of the exiled sorcerous Prospero, engaged to Ferdinand, the prince of Naples. Having spent most of her life on an island with only her father and various supernatural beings for company, she falls hopelessly in love with the first young man she sees. Katherine Duckett’s fantasy novel picks up from there and describes what happens when Miranda, back in her ancestral home in Milan, meets a mysterious serving girl named Dorothea. It’s lust at first sight as she explores the brave new world of same-sex attraction. Perhaps being raised by a warlock made it inevitable that Miranda would fall for someone like Dorothea, a witch with a murky past who can alter her appearance and enter other people’s dreams while they sleep.

Although the main characters are drawn from Shakespeare, Miranda in Milan’s plot is derived from classic Gothic novels. Upon arriving in Italy from their enchanted island, Prospero forcibly separates Miranda from Ferdinand and takes her to their family palace in gloomy Milan. Miranda is locked in her chambers like a prisoner with few visitors except for a grim governess and Dorothea. Luckily, escape is easy because Prospero’s palace has more hidden passages than Otranto’s castle. Miranda finds herself at the center of several mysteries, including a portrait that must remain covered by decree, a masked figure who wanders the hallways at night, a prisoner locked deep underground, and necromantic shenanigans in a secret laboratory. With a little help from Dorothea’s witchcraft, Miranda solves these puzzles, overthrows the patriarchy, and even questions her own role as a privileged colonialist. It may seem like a lot to pack into a short book, but Duckett keeps the plot focused and the writing brisk as she moves toward a sunny ending.

Peter Muise

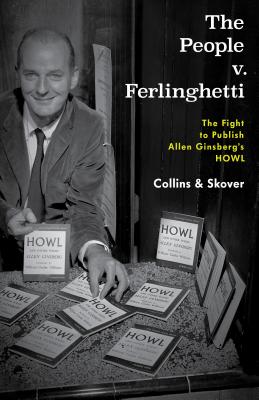

The People v. Ferlinghetti: The Fight

The People v. Ferlinghetti: The Fight

to Publish Allen Ginsberg’s Howl

Edited by Ronald K. L. Collins & David M. Skover

Rowman & Littlefield. 216 pages, $30.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti isn’t gay (he’s still with us at age 100), but he played a unique role in the LGBT history when he decided to publish Allen Ginsberg’s Howl in the not-very-queer year of 1957. After that, talk about gay sex became much more public. For Ginsberg, his eventual victory in court was the release valve for immense sales of Howl, which remains in print to this day as a sort of mid-century queer outcry, Whitmanesque in its spectacular spray-nozzle of words and ideas, if more colorful in terminology. For Ferlinghetti, the victory was that of a tiny publisher over a crude effort at censorship.

The book is mainly about this legal fight and includes the previously unpublished opinion of Clayton Horn, a municipal judge whose religious background and apparent inexperience with major cases had made Ginsberg’s camp nervous. But Horn did an exceptional amount of research and concluded that “if the material has the slightest redeeming social importance it is not obscene.” The rest of the opinion includes a series of mechanisms for evaluating such cases and some exceptionally clear defenses of the First Amendment: “Would there be any freedom of the press or speech if one must reduce his vocabulary to vapid and innocuous euphemism?” Thus did Ginsberg’s straightforward talk about gay sex—fellating sailors and ass-pumping motorcyclists—walk unfettered out the door of City Lights Books to become a beacon for writing about gay sex. This book would have benefited from a more thorough editing, but as a reference on a free-speech victory for LGBT people, it fills a clear need and tells a good story.

Alan Contreras

This documentary film follows the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus and the Oakland Interfaith Gospel Choir on a five-state tour through the Deep South, where they performed in churches, community centers, and concert halls. The idea originated with Tim Seelig, conductor and artistic director of the San Francisco group, who thought such a tour would be a good way to bring a message of LGBT inclusion to the Bible Belt. A secondary goal was to help some chorus members who were raised in the South to re-connect with their families and to assist them, if possible, in addressing unresolved wounds with family and friends. (Venues were selected based on these individuals’ community contacts.) Eight or so choir members’ stories are told in sequence, including that of Seelig himself, who was raised in the Baptist faith and confronts his painful memories of attending a Southern Baptist church thiry years ago. Another chorus member hopes the tour will help him to reconcile with his conservative father. These encounters provide the film with lots of happy endings and leave the viewer feeling that the tour did some good in bringing these two separate worlds together.

Stephen Hemrick