This coffee table book is one of many books commemorating Stonewall’s fiftieth anniversary, with 200 photographs from the twenty years following the 1969 event. Most of the photos are ones that I had not seen before in art history or photojournalism books. A few that really jumped off the page for me are Raven (Gun), by Catherine Opie, Floating, by Morgan Grenwald, and The Piers (Three Men on Dock), by Alvin Baltrop, with its eerily tranquil atmosphere only vaguely hinting of lurking perils. The book is divided into seven well-chosen sections, such as “Coming Out,” “Sexual Outlaws,” and “Uses of the Erotic.” Each section includes an introduction that provides a synopsis of the pictures to come. The general intro explains that the book intends to examine “the impact of the lgbtq movement on the art world,” and the section openers succeed in taking us beyond the descriptive and theoretical toward actually documenting this impact. For example, the magazine The Blatant Image: A Magazine of Feminist Photography was short-lived but still a breakthrough showcase for queer women photographers. The years from 1969 to 1989 tell a particularly poignant story, starting with the Stonewall era and ending at the height of the AIDS crisis. Many of the photographs, posters, and other artwork become that much more meaningful when viewed through the lens of our own time.

Peter Marino

In the Valley of Tears

In the Valley of Tears

by Patrick Autréaux

Translated by Eduardo A. Febles

The Unconscious in Translation (UIT Books)

117 pages, $19.95

Originally published in French in 2009 and newly translated into English by Eduardo A. Febles (who is on the Board of Directors of this magazine), this is a brief, somber, and certainly somewhat autobiographical novel about an unnamed narrator’s cancer diagnosis and treatment, and his relationship with his long-term partner. Patrick Autréaux, who started out as a psychiatrist, is acclaimed in France for his fiction, nonfiction, and poetry. He was in his mid-thirties when he was diagnosed with lymphoma, and underwent surgery and chemotherapy in Paris. The book resonated with translator Eduardo Febles, a professor at Simmons University in Boston, who experienced his own cancer diagnosis and treatment.

In the Valley of Tears’ narrator is involved in a transatlantic relationship with Benjamin, an American physician based in New York City. They had met a decade earlier, when Benjamin was studying in Paris. Though Benjamin takes exquisite care of him (“the man in him [was]… replaced by an angel”) the relationship suffers. Later, when the narrator finds—to his delighted surprise—that he is healthy again and filled with sexual desire, he begins seeking “different bodies, for exotic encounters.” He’s following Susan Sontag’s advice, also used as the book’s epigraph, which she recorded in her journal when she was receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer: “In the

valley of sorrow, spread your wings.” The narrator calls himself a “sacred whore” (putain sacrée, in the original) who is “fascinated by the diversity of [his]desire.” Though he and Benjamin are in agreement on non-exclusivity, their relationship does suffer. The ending, set in an STD clinic where Benjamin is being treated, can be seen as inconclusive, and leaves the reader wondering: well, now what?

Martha E. Stone

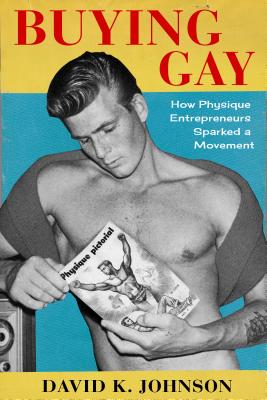

Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked a Movement

Buying Gay: How Physique Entrepreneurs Sparked a Movement

by David K. Johnson

Columbia University Press. 320 pages, $32.

In his history of early American physique photographers, David K. Johnson maintains that they were not just a byproduct of the early homophile movement, but a catalyst to it. These entrepreneurs supported the movement financially and by fighting the legal battles that liberated it. The story begins in Los Angeles with Bob Mizer (1922–1991) and his Athletic Model Guild. Mizer fought the postal authorities and went to prison for his work. He photographed well over a thousand models, with whom he had great rapport. In his best photos and movies, the models seem proud and happy to be displaying their bodies. Others in Buying Gay include Greenberg Publishers (founded 1931), which published early gay novels and The Homosexual in America, by “Donald Webster Cory” (pseudonym for Edward Sagarin). There were Randolph Benson and John Bullock and their Grecian Guild, which envisaged a comprehensive gay community. Lynn Womack built a gay empire and successfully took on the viciously anti-gay postal authorities. And there was Directory Services, Inc. (DSI), founded in 1963, which won a court decision against the Post Office—a landmark victory for gay rights. Johnson concludes: “The business of producing and disseminating homoerotic images helped forge a movement.” This book tells an important part gay history.

A longer piece on this topic will appear in a forthcoming issue of this magazine.

John Lauritsen

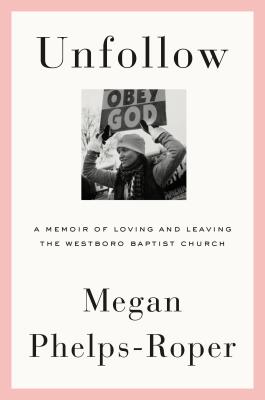

Unfollow: A Memoir of Loving and Leaving the Westboro Baptist Church

Unfollow: A Memoir of Loving and Leaving the Westboro Baptist Church

by Megan Phelps-Roper

Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 304 pages. $27.

Brace yourself for the harrowing, gut-wrenching and often heartbreaking story of Megan and Grace Phelps-Roper’s escape from the Westboro Baptist Church. LGBT readers will know the WBC due to its sheer homophobic extremity, a tone set by its founder, the late Fred Phelps. Phelps and his church members (mainly also his family members, as he had umpteen children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren) became notorious for their protests, which included signs that read (among other things) “God Hates Fags.” In vivid detail, Phelps-Roper recounts the various epiphanies that led her to realize that the strict Christian fundamentalist philosophy she had been brought up on and the extreme micromanaging of every aspect of their lives—“an Orwellian level of control over our every word, our every movement”—meant that she had to get out. But the decision to leave the compound, and the courage it took to act, took time, as the two sisters weighed the considerable cost of leaving. It would mean a clean break from the all-or-nothing ties to their family, almost certainly resulting in never seeing their parents or siblings again. Phelps-Roper is a fine writer, full of insights into how the scripture was twisted to meet the bigoted means of the WBC, and what incredible moments awaited her once she had broken free of the constraints of this cult. Unfollow plays out like a gasp-inducing thriller, a page-turner that will no doubt make a great film one day.

Matthew Hays