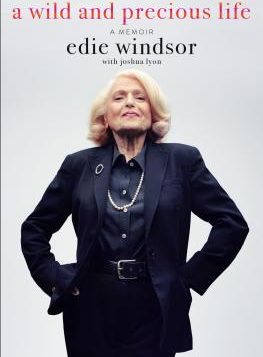

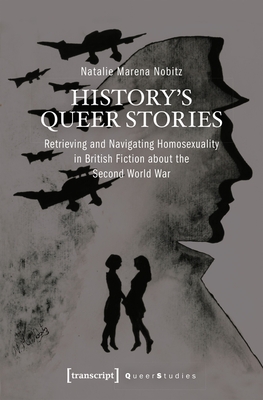

History’s Queer Stories: Retrieving and Navigating

History’s Queer Stories: Retrieving and Navigating

Homosexuality in British Fiction about the Second World War

by Natalie Marena Nobitz

Transcript–Verlag. 310 pages, $45.

Gay fiction before Stonewall is widely assumed to be bleak and despairing in its depiction of LGBT people at odds with social norms. In History’s Queer Stories, Natalie Marena Nobitz takes issue with this assumption, arguing that there was a surprising amount of literature that did not fit this mold. Focusing on novels such as Mary Renault’s The Charioteer (1953) and Walter Baxter’s Look Down in Mercy (1951) as well as books by Quentin Crisp and others, Nobitz stresses that these works are often strikingly matter-of-fact, even unapologetic, in their depictions of homosexual desire.

Many have pointed out that during World War II, men and women were suddenly thrust into very close contact with each other, as well as into nontraditional roles (especially women). But Nobitz takes this a step further and looks at how these writers were affected by the carnage that resulted from traditional norms of masculinity. Thus, for example, in The Charioteer, the main character is not only gay, he is also a conscientious objector. Nobitz argues that by opting out of the traditional male role of soldier, he actually carves out the space he needs to be gay—something he’s not particularly ashamed about. Or as Quentin Crisp cheekily declared: “No-one expected the war to be about an unemployed and effeminate homosexual who struggled for money or about a lesbian couple and their endeavors to stay together despite all odds.” And yet, as this book points out, such arrangements were not as unusual as might be supposed.

Dale Boyer

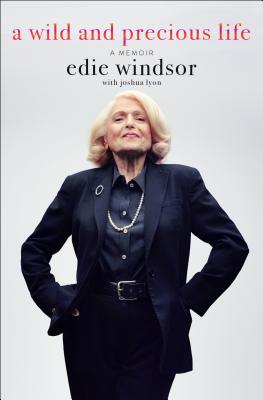

A Wild and Precious Life: A Memoir

A Wild and Precious Life: A Memoir

Edie Windsor, with Joshua Lyon

St. Martin’s Press. 288 pages, $23.95

Edie Windsor was the headliner in the 2013 case (U.S. v. Windsor) that struck down the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) and paved the way for marriage equality. Her partner of forty years had died, leaving Edie burdened with inheritance taxes that wouldn’t have been levied in a heterosexual marriage. Well-known among activists, she was represented by high-level attorneys who used a Due Process argument to win the day.

A Wild and Precious Life, Edie’s autobiography, sparkles with her life of brave decisions. Was it just looks, brains, extroversion, inordinate self-confidence, an innate sense of justice and decency that made her the powerhouse she was? Edie’s storytelling fuels such ruminations. Born in 1929 in Pennsylvania to a working-class Jewish family of strong personalities, she knew early on that she was lesbian. This was the 1940s, so she gave traditional marriage a shot, but a year later she was divorced and on her way to New York City, where she became a denizen of those legendary lesbian and gay bars of old Greenwich Village. A math whiz, she graduated from NYU and ended up working at IBM, becoming one of the first women in computing. Next she met Thea, a respected clinical psychologist, and soon the two lovebirds became a power couple.

Because Edie died before completing her story, author Joshua Lyon has added useful context between chapters. Edie left her money to many causes in the community, including SAGE, a service organization for LGBT seniors. Edie Windsor’s life was graced with intelligence, courage, and parties, as is this autobiography.

Sarah Sarai

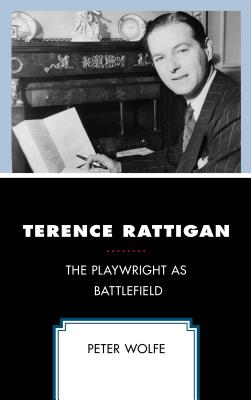

It’s difficult to know just who the intended audience for Peter Wolfe’s book about Terence Rattigan might be. Rattigan was in his time the most successful and prolific of British playwrights (The Browning Version, The Winslow Boy, Separate Tables). But he became démodé in 1956 when the first of the angry young men plays, John Osborne’s Look Back In Anger opened. In Rattigan’s plays people entered through French doors; in Osborne they screamed at each other in the kitchen. While Rattigan went on writing for another twenty years, and even helped produce Joe Orton’s Entertaining Mister Sloane, he was simply out of fashion.

He was also a tortured homosexual, a playwright whose characters portray the terrible loneliness of people for whom sex never works out. In Rattigan’s vision of things, Wolfe says, whether you have sex or you don’t, you’re doomed. Though Wolfe makes frequent references to Rattigan’s life—his problems with alcohol, gambling, homosexuality, success, his less than admirable father, the suicide of one of his lovers—this book is not a biography. It’s primarily a detailed summary of a selected number of Rattigan’s plays. It’s so scene-by-scene that it reads a bit like the “color commentary” of sports journalists describing a football game. Theater majors and mavens may love this book; the rest of us may be left with a desire to read one of the biographies cited in the bibliography.

Andrew Holleran

Lisa Jarnot’s 2012 biography, Robert Duncan: The Ambassador from Venus gives us a view of the poet’s life but a limited view of Duncan’s life partner, collage artist Burgess Collins, better known as Jess. In The Householders, Tara McDowell offers a detailed look at how Duncan and Jess lived and worked together as a couple in San Francisco from 1951 until Duncan’s death in 1988. Duncan and Jess exchanged marriage vows when they moved in together. In the 1950s there were no norms for what a gay male household should or could be. This book provides a record of what that household became, though whether it could be a model for gay couples is debatable. Chalk it up to the distinctive personalities and work styles of the two artists. The book returns often to the question of what makes a family and how queer families are generated. Duncan the poet wanted what he thought of as a “household” in which to do his work. He described this as “a lone holding in an alien forest-world, as a campfire about which we gatherd in an era of cold and night—a made-up thing in which participating we have had the medium of a life together.” The poet and the self-described “housewaif” built a distinctive domestic space for their work, and ultimately it was their work that mattered, then and now.

Alan Contreras