Falling

Falling

by Trebor Healey

Univ. of Wisconsin. 262 pages, $26.95

Wanderers, immigrants, and others unmoored in space and adrift from their emotions populate the tales in this new short story collection by Trebor Healey. Most of the stories take place in Mexico, the American Southwest, and Argentina; but despite the sunny climes, death and how we deal with it is a prominent theme. In “The Falling Man,” the collection’s opener, a tourist falls off his hotel balcony in Acapulco and develops amnesia. Following a vague instinct, he leaves the resort in search of a famous butterfly reserve in a nearby town. The story begins as a dark comedy but ends with a surprising jolt of sexuality and mournfulness. Butterflies also figure in “300 Insurgentes,” in which a young man from rural Chiapas gets a job guarding an abandoned luxury apartment building in Mexico City. He soon learns the building is haunted by the ghosts of those who died unjustly—and there are a lot of them.

Although not all of Falling’s protagonists are gay, many are. In “Nogales,” an immigration lawyer in a bad relationship falls in love with the man who almost ran him over while fleeing the police. An aimless gay dilettante drifts around in “Rite of Passage,” taking drugs, sleeping with artists and hippies, and not facing what he needs to until it’s almost too late. In “Ghost,” we follow an American tourist through bohemian Mexico City and witness him falling in (and out) of love with a heroin-addict hustler whose father may be a famous poet. An Argentine political consultant tries to create the gay version of Eva Peron in “The Orchid,” Falling’s novella-length closing story. When his plans go badly awry, we’re not surprised: the consultant is mourning his recently deceased daughter, and his scheme was inspired by a dream about a skull-faced Evita.

Peter Muise

Norman Hartnell: The Biography

Norman Hartnell: The Biography

by Michael Pick

Zuleika. 734 pages, $34.52

Sir Norman Hartnell (1901–1979) matters to anyone interested in the modern British monarchy, because he created many of the iconic dresses worn by the Queen Mother and by Queen Elizabeth II. Along with a few others, such as Victor Stiebel and Hardy Amies, he created a distinctively British take on high fashion that deviated from modern trends in France and the U.S. His forte was aristocratic glamour of a kind that faded during the 1960s. Although his business thrived for many years, he was not a natural businessman. Nor was he, strangely enough, a natural fashion designer, since he never learned to “cut or sew, much less fit a garment.” He did know how to draw and paint clothes, but many of the images that bear his signature were executed by assistants.

So why was he a success? Perhaps the answer was his charm, which he applied not only to his female clients but also to the men that he admired. As Pick observes: “it will not surprise the reader to learn that Norman was homosexual from his boyhood on.” His business and sexual tastes were aligned through the medium of role-play. He had enjoyed cross-dressing in theatrical productions as a student at Cambridge, and he reprised one such character in particular, “Miss Kitty,” whose pleasure it was to be “menaced by a large male partner with a riding crop and finally violated with considerable force.” The book includes a delightful 1945 illustration of Hartnell’s “male ideal.” The effect is halfway between Liberace and a British guards officer. Alas, the social mores of the times meant that, while he was well paid for creations for socialite women, he had to keep his tastes in male style a secret.

Dominic Janes

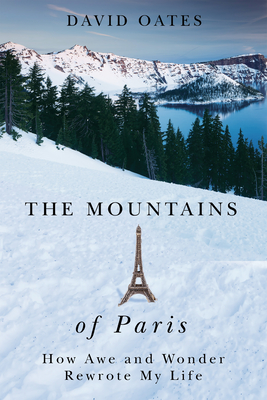

The Mountains of Paris: How Awe and Wonder Rewrote My Life

The Mountains of Paris: How Awe and Wonder Rewrote My Life

by David Oates

Oregon State Univ. 178 pages, $22.95

Noted back-country climber David Oates is perhaps best known for Paradise Wild, his manifesto on the way humans fit into the natural world. In that book and in The Mountains of Paris, a recurring theme is his upbringing in a conservative religious household (“I am the gay son they never wanted”). Both books focus on his ways of coping and becoming more free as a gay person. As Paradise Wild used the metaphor of escape via the Sierras as its principal route to sexual salvation, The Mountains of Paris uses the image of ascending a mountain to confront personal demons or to be awestruck by a painting. Flashbacks to his youth bring us the golden-fleshed Tommy—someone who, like Gore Vidal’s Jimmy, perhaps, we all knew in our youth. The music of Schubert heard, played, and imagined flows through much of Paris along with the author. Youthful reminiscences of C.S. Lewis contrast with the delicate faith of a mature man. Oates calls his re-rooting as an adult being in “the deep present.” It is certainly a gift to all of us to be able to walk with him in his days and nights of Parisian discovery, as much John Muir as Ned Rorem, blending the richness of church as it should be with the pine-scented cirques of his doubting youth.

Alan Contreras