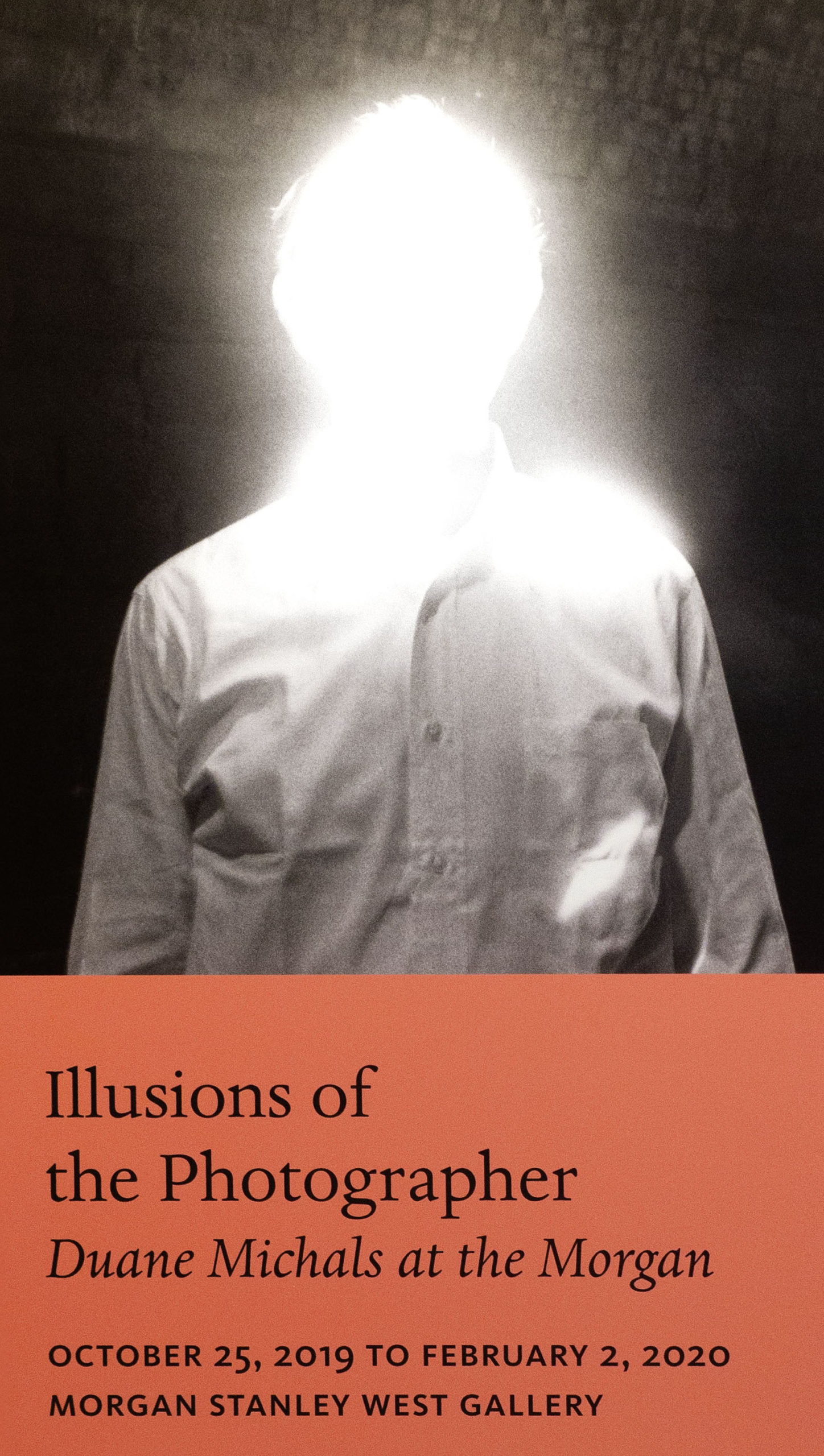

Illusions of the Photographer: Duane Michals at the Morgan

Illusions of the Photographer: Duane Michals at the Morgan

Exhibition at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York City

October 25, 2019–February 2, 2020

Catalog edited by Joel Smith

AFTER an eight-hour exposure in a camera obscura, a light-sensitive chemically treated pewter plate produced a rudimentary negative that revealed an image of rooftops and trees. Nicéphore Niépce titled the landscape, the first photograph ever made, “View from the Window at Le Gras.” From that moment in 1826 to the present, the æsthetics, practice, and theory of photography have been deliberated within two oppositional paradigms.

The first paradigm, termed “pure” photography or photorealism, includes the subgenres of documentary, photojournalism, and candid street images. These are unmanipulated images in sharp focus believed to be authentic, visual representations of reality. The second, “fine art” or conceptualist photography, a spin-off from Pictorialism (a late 19th and early 20th-century style) highlights the imaginative content of images through tonality and composition, with subject matter that evokes fantasy, dreams, memory, and metamorphosis. These images often use costuming and elaborately constructed stage-set designs that blend reality and fiction to create cinematographic or theatrical tableaux. Duane Michals is an artist who belongs to the second school of photography.

Illusions of the Photographer: Duane Michals at the Morgan was a comprehensive retrospective at the Morgan Library & Museum, curated by Joel Smith, the institution’s groundbreaking first curator of photography. Michals’ photography epitomizes the conceptualist method—narrative and performed, illusionistic and dreamlike. In addition to his well-known black-and-white sequences and portraiture, the exhibition includes color chromogenic prints, mixed-media paintings, and objects and stills from his short films, sixteen of which were screened during the run of the exhibition. Juxtaposed against his work are sixty diverse examples of art and artifacts dating from the 18th to the 20th centuries, selected by Michals after a two-year exploration of the Morgan’s extensive archives.

Michals has opinions on a range of subjects from deconstructionist philosophy to street photography. To make a point, he will sometimes wear costumes to become his own subject, as in the satiric sequence Who Is Sidney Sherman? (2000) (unfortunately not in the exhibition), in which he sports a blond wig and dangles a cigarette, a parody of photographer Cindy Sherman. Included is a lengthy caption that reads in part: “Sidney paints his fingernails pink, a brilliantly audacious gesture that exposes the dis-corroborative of Revlon’s vacuity while trenchantly confirming lipstick as a phallic ploy of alpha males vis a vis [sic]Derrida’s strategies of discorroboration.”

Michals derides photographers for their quasi-fetishistic preoccupation with equipment: “Can you see Joyce, Steinbeck, and Hemingway sitting around comparing typewriters?” Of street photography he says: “Without those rocks and trees and those funny looking people standing on corners eating carrots with American flags would we have a picture to take? We are what we feel, not what we look at. The best part of us is not what we see. We are not eyeballs.” (All quotations in this essay are from newspaper and video interviews that were conducted from 1981 through 2019.)

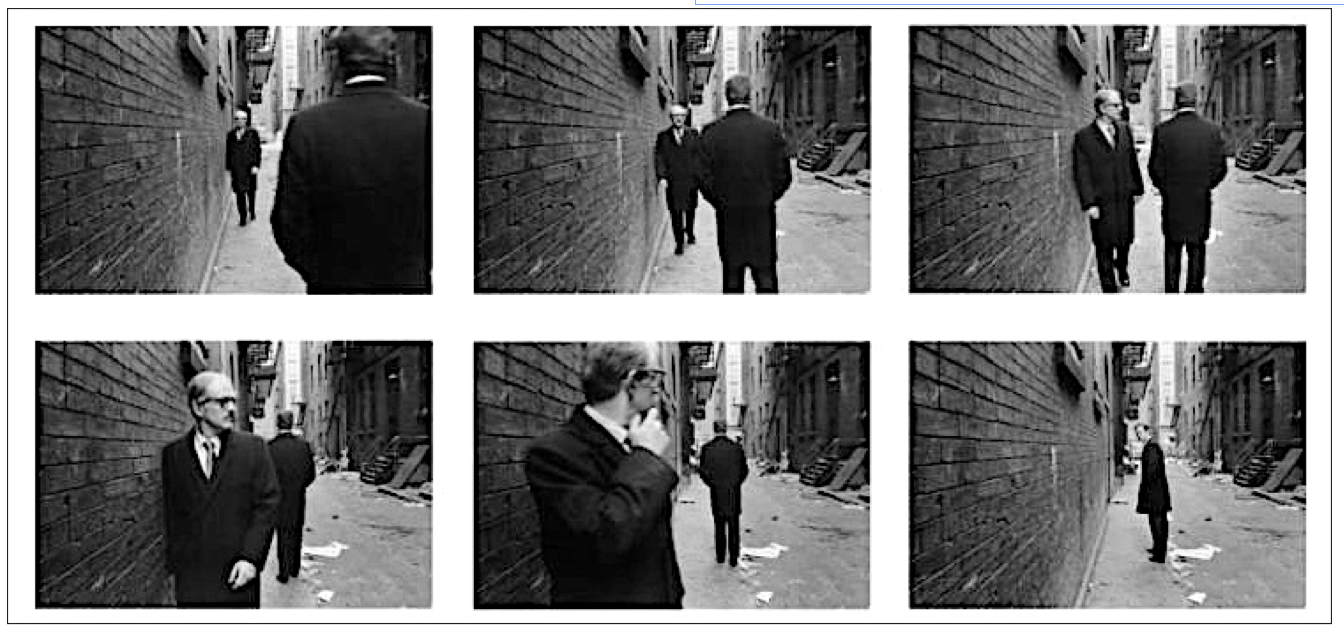

First and foremost, Michals is a storyteller, turning the camera on himself at times to create frame-by-frame narratives in which he poses and performs as the subject in a mise-en-scène. He defies the constraints of visual language and structure by incorporating handwritten textual commentary or narrative directly onto the borders of photographs. While the use of definitional titles for artwork is ubiquitous, the interconnectivity of sequential images and the conjunction of text and image are distinctly Michals.

Nevertheless, these features of his work—homoeroticism, performativity, self-representation, storytelling, and theatricality within images—have been present since the early days of photography. For example, American photographer F. Holland Day made a portfolio of 250 photographs from 1895 to 1898 performing as Jesus Christ, having prepared for three years by going on a starvation diet, growing an unkempt beard and long hair, and importing a wooden cross from Syria and costumes from Egypt. Despite Day’s use of religious symbolism, there are unmistakable homoerotic references in his photographs, as Shawn Michelle Smith asserts in At the Edge of Sight: Photography and the Unseen (2013): “While some historians of photography have had difficulty discussing Day’s images as erotic, historians of queer visual culture have not.”

Michals scoffs at the necessity for extensive preparation for his sequences. “Most of the work is done in my head. So when it comes to the actual shooting time, it’s very easy. I can do the whole thing in about an hour.” However, his work derives from lifelong personal explorations into memory, mortality, temporality, sexual orientation, and spirituality. The photographs are deeply affective, whether extracted from an autobiographical core about early childhood at the precipice of trauma or drawn from the psychological realities of modern life, including queer genealogies and experience, such as the iconography of gay-male cruising in Chance Meeting (1970). It is all accomplished within the vernacular of nocturnal cityscapes. In Empty New York: Subway Interior (1964) from his monograph Empty New York, he captured the demimonde of sidewalks at dawn or dusk along with deserted subway stations, diners, storefronts, and vacant theaters (also hauntingly photographed in the 1970s by Peter Hujar and published in 2005 as Night).

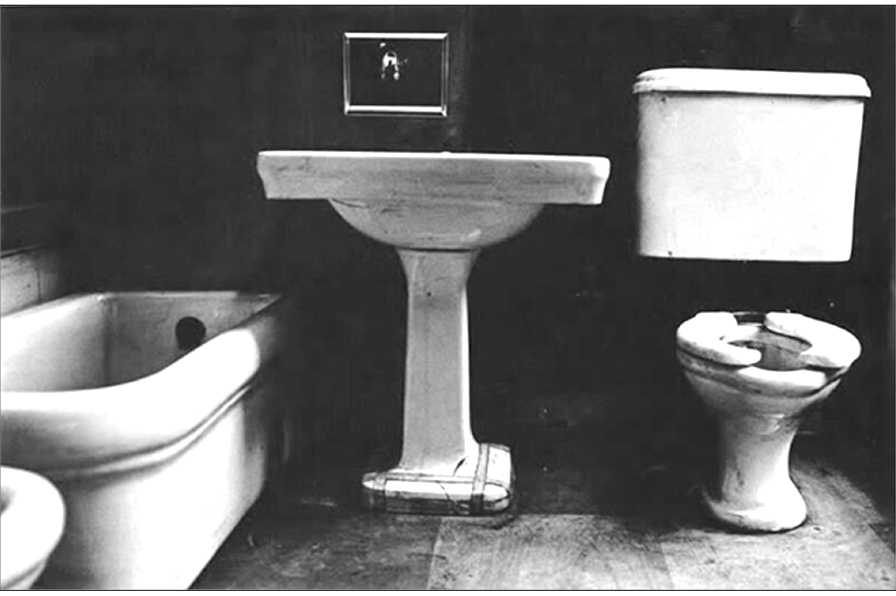

The imaginative challenge for Michals is about using visual images to convey abstract ideas: how to photograph the ephemeral, that which is imaginative, intangible, invisible, or subconscious. He writes: “Photographers feel comfortable photographing what they see. But they never try to photograph what you can’t see.” In the 19th century, British photographer Julia Margaret Cameron utilized similar methods, such as soft focus and low lighting, incorporating chemical stains, fingerprints, smudges, and scratches. She used swirls of drapery to enhance the dreamlike quality of her images. Like Cameron, Michals uses diaphanous drapery to evoke the ethereal, as in Warren Beatty (1967) and Certain Words Must Be Said (1976). When he plays with “properties” of mirroring, reflections from various angles, as in A Story About A Story (1989), he illustrates the blind spots, boundaries, and limitations of perception. He claims that reality is relative: “How do you know that my reflection is the real one? It’s all in your mind, you know. The mirror reflects everything.” Or: “I am a reflection photographing other reflections within a reflection.”

The imaginative challenge for Michals is about using visual images to convey abstract ideas: how to photograph the ephemeral, that which is imaginative, intangible, invisible, or subconscious. He writes: “Photographers feel comfortable photographing what they see. But they never try to photograph what you can’t see.” In the 19th century, British photographer Julia Margaret Cameron utilized similar methods, such as soft focus and low lighting, incorporating chemical stains, fingerprints, smudges, and scratches. She used swirls of drapery to enhance the dreamlike quality of her images. Like Cameron, Michals uses diaphanous drapery to evoke the ethereal, as in Warren Beatty (1967) and Certain Words Must Be Said (1976). When he plays with “properties” of mirroring, reflections from various angles, as in A Story About A Story (1989), he illustrates the blind spots, boundaries, and limitations of perception. He claims that reality is relative: “How do you know that my reflection is the real one? It’s all in your mind, you know. The mirror reflects everything.” Or: “I am a reflection photographing other reflections within a reflection.”

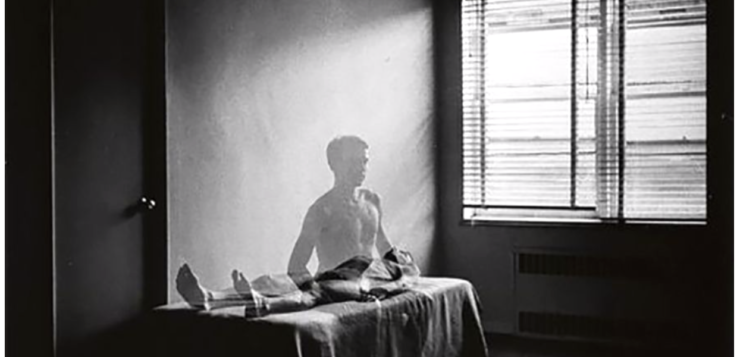

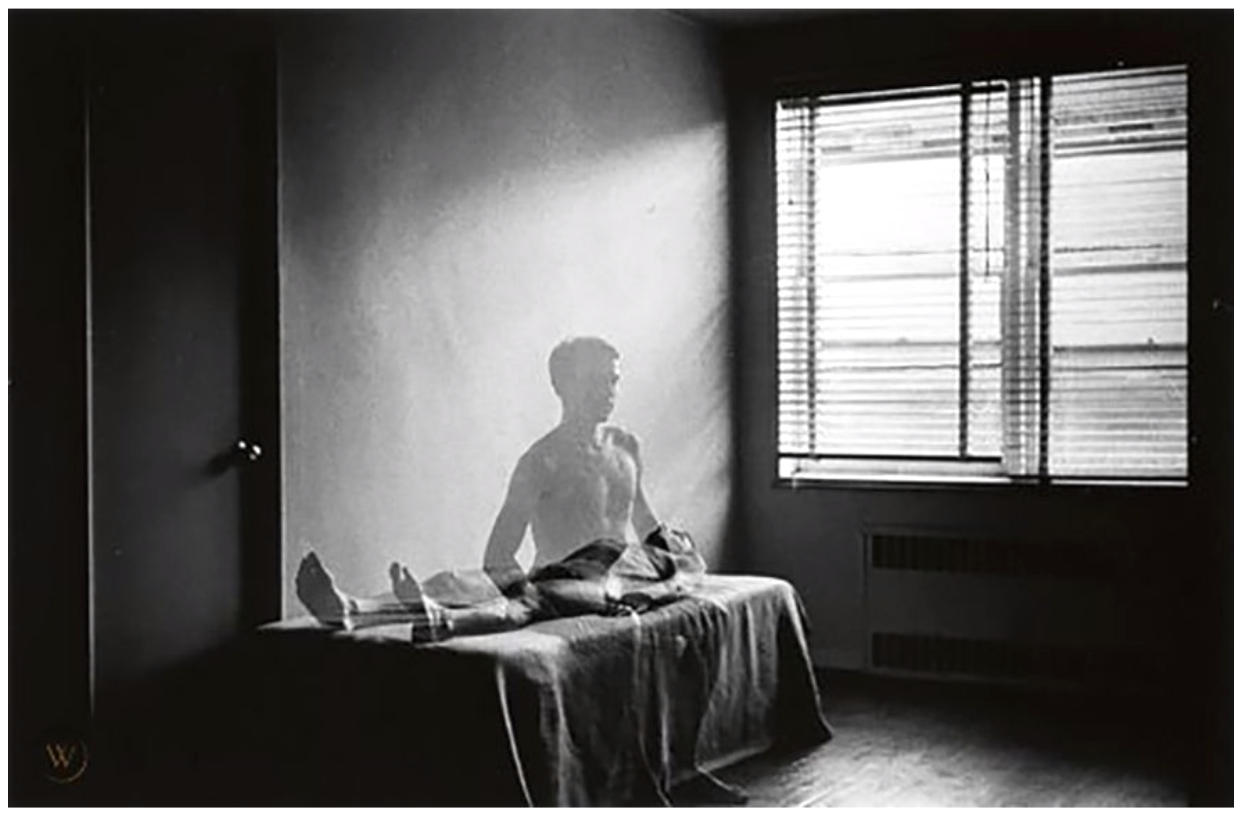

In A Short History of Photography, philosopher Walter Benjamin declared the “optical unconscious” as one of photography’s revelations, the camera’s technical capacity to make visible what usually evades perception. Michals explores what is hidden, unseen, or outside the frame, which he references in several portraits, such as Andy Warhol (1958) with hands over face and Magritte with Hand Over Face Exposing One Eye (1965). Photographs have the talismanic authority to make visible that which is unseen, and to allow us to see metaphorically beyond the literal representation. In Michals’ words: “I believe in the imagination. What I cannot see is infinitely more important than what I can see.” In The Illuminated Man (1968), the figure projects the sheer energy of the optical unconscious. “With this man I wanted to do a picture where you could see the mind working.” Michals believes the mind is luminous. In The Human Condition (1969), a set of six images, a man on the IRT 14th Street subway platform fantastically explodes beyond his human form into an astronomical diagram of the Milky Way.

Starting in the mid-19th century, spiritualists, psychics, and mediums attempted to communicate with the dead through the camera, creating a genre of spirit photography. Photographs can sometimes capture more than the eye can see. Michals summons a ghostly apparition by means of double exposure, reviving the ethereal iconography of 19th-century spirit photography in a new poetic context. In The Spirit Leaves the Body (1968) he uses double exposure to create ghost-like images. He exploits this and other techniques, such as intricate imagery and the use of mirrors, to convey abstract ideas or belief systems or to communicate emotional states. Other works in which he uses double exposure to achieve different results include George Balanchine and Dancers (1960) and René Magritte at his Easel (1965).

Now 87, Michals has explored mortality in so many of his images that it prompted Joel Smith, in the exhibition catalog interview, to ask him: “You’ve been preoccupied with mortality since age thirty, at least! Why do you think that is?” Replied Michals: “From the beginning! I have no idea.” Susan Sontag wrote in On Photography: “All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability.” Many late 20th-century photographers, particularly during the AIDS epidemic, explored mortality in photographs, such as in Candy Darling on her Deathbed (1973), by Peter Hujar; Robert Mapplethorpe’s Self-Portrait (1988); and David Wojnarowicz being buried alive in Face In Dirt (1991).

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes defined “affective intentionality” as the method by which to interpret or read a photograph. The image must be “steeped in desire, repulsion, nostalgia, and euphoria.” Michals sums up his guiding principle: “A good photograph should have emotional impact.” Whether he’s having a conversation with a duck, impersonating the devil, wearing a clown’s red nose or a bowler, standing over his own corpse, dancing on the Brooklyn Bridge, demonstrating at Trump Tower, or howling at the moon from a rooftop, Michals celebrates the human condition. “I wish we realized that we are queer creatures. It’s a queer life. The universe is queer.”

Steven F. Dansky has been an activist, photograper, and writer for more than fifty years. He is the co-founder of the video projectOutspoken: Oral History from LGBTQ Pioneers.