Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals

Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh

Nov. 1, 2014 to Feb. 16, 2015

Peabody Essex Museum, Essex, Massachusetts

March 7 to June 21, 2015

Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals

Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals

Edited by Linda Benedict-Jones

Prestel. 240 pages, $75.

“A camera is like a typewriter, in the sense in which you can use the machine to write a love letter, a book, or a business memo,” the photographer Duane Michals said in a 2001 interview with Italian critic Enrica Viganò, which is reproduced in Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals. He added that some photographers use a camera “simply to document reality: a face you pass on the street, a car accident. I think the camera can also be used as a vehicle of the imagination.” Produced as the catalog for a retrospective exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh earlier this year and currently the Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts, Storyteller presents critical essays, early and recent interviews with the artist, and reproductions of some of his more important series.

Michals has used the camera as such a vehicle for over fifty years, producing a still-growing portfolio of work that has often challenged our notions of what photography should look like in both form and subject matter. When he started out taking photographs in the 1960s, he had little interest in the kind of Cartier-Bresson “decisive moment realism” that was the genre’s dominant æsthetic. Instead, he explored photography’s creative and invented potential using double and long exposures, creating

narrative sequences made up of images, often adding lyrical captions in his own handwriting—which, he once said, turned the mechanical form of the photograph into a unique and personal work.

These elements combine to produce thoughtful and deeply intimate images. To encounter a Michals photograph is to be caught

somewhere between a poet’s concern for language and detail, a photographer’s eye for the quotidian, and a surrealist’s use of juxtaposition and illusion. (He has had a long-standing fascination with Belgian painter René Magritte and did several portraits of the artist and his wife in the 1970s.) He has explored this unique alchemy over the years, exhibiting in solo and group shows in the U.S. and abroad and publishing over twenty photo books. But his place in the art world has often been a mixed one: critics have described his work as everything from sentimental to powerfully inventive.

Born in 1932, Michals was raised in a working-class neighborhood outside of Pittsburgh. His father was a steelworker and his mother worked as a live-in domestic

servant, leaving Michals to be raised by his Slovak immigrant grandparents, who spoke little English. His upbringing was quite similar to that of his contemporary, Andy Warhol, who also grew up in an immigrant, working-class Slovak family in Pittsburgh. Both men would ultimately leave home to study art and would eventually land in New York, where they would start their creative careers in commercial art. But Warhol’s aloof and ironic stance in both his public persona and his art—as well as his meteoric rise to celebrity status—contrasts sharply with Michals’ expressive sincerity, emotional acuity, and oftentimes comic play in his art. “He has never been a photographer’s photographer,” writes Linda Benedict-Jones, the exhibition curator and chief writer for this collection, in her introductory essay. She adds that despite this marginal position among his peers, “he has carved a place for himself in contemporary art history and left an indelible mark on all kinds of people who trade in human communication and visual expression.”

As the essays in this collection show, it is Michals’ intimacy of ideas and emotions that define his work and its appeal. Allen Ellenzweig’s essay, “Wounded by Beauty,” begins with an early encounter with Michals’ Paradise Regained, a 1968 series of images that captures a young man and woman staring back at us as they sit in a sparse apartment, dressed in business attire. As the series progresses, the furniture is replaced by an increasingly dense forest of plants, and the man and woman lose layers of clothing, “gradually reveal[ing]themselves in the glory of their nakedness and sinless innocence.” But it is the seductive image of Adam, who sits closest to the camera, muscled and angelic, that attracted Ellenzweig’s eye, prompting him to wonder in that first encounter: “Who was this photographer who placed before my eyes a figure so luscious and seductive? How did he, this Duane Michals, know my secret?” It is this kind of provocative intimacy, this secret of visual expression, that has made Michals’ work so compelling within late 20th-century gay imagery.

In such important works as Homage To Cavafy (1978), The Nature of Desire (1986), Narcissus (1986), and Salute, Walt Whitman (1996), Michals merged the personal with the historical and the mythical through a visual language of desire that appears always just out of reach. Unlike the younger generation of gay-identified photographers working in the late 1970s and ’80s for whom homoerotic desire was their explicit subject (notably Robert Mapplethorpe), Michals offered, in Ellenzweig’s words, “indirection, ambiguity, metaphor” as ways to engage with “same-sex amity, physical adoration, and romantic longing in images that are staged to mysterious, poetic effect.” In some sense it is the idea of desire, with its visual and poetic uncertainties, rather than its actuality that motivates Michals in such works.

What is clear throughout the essays and interviews is how Michals saw his place in 20th-century photography, which was precisely through his resistance to its demands. When The New York Times featured Michals in an interview just before the exhibition at the Carnegie Museum opened, they titled the piece “Documents of a Contrarian.” This title underscored not only the artist’s direct and sometimes flat criticisms of art world pretensions (most acutely demonstrated in his visual satire of artists such as Cindy Sherman and Andreas Gursky in his 2006 Foto Follies: How Photography Lost Its Virginity on the Way to the Bank), but also suggested the ways in which he taught himself (and others) the freedom to push at the boundaries of photographic art.

Max Kozloff, in his essay on Michals’ most recent work of painting brightly-colored modernist and surrealist designs on 19th-century tintypes, thinks they evoke a collage-like discontinuity between past and present in which the earlier image becomes a disembodied portrait, reconfigured in the present under Michals’ brushstrokes. As Kozloff writes, photography for Michals is “a ghostly medium, since it transcribes appearances but lacks substance, forever disallowing our touch.” We experience this in so many of his images that play with shadows and ghostly figures, images haunted by a presence seen and unseen.

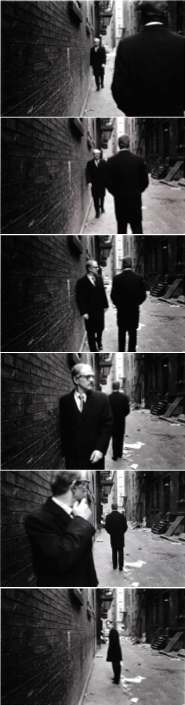

In a series from the 1970s titled Chance Meeting, we watch the alleyway encounter of two men in business suits, their bodies passing in silence. In the first few images, we encounter the scene from just behind one man’s shoulder, looking down the alley as the other approaches in the distance. The photographs move like a series of film stills as the two men encounter each other, exchange glances, and turn backwards to look as the space between them grows. The final image presents just the one man, staring back at us down the length of the alley. Throughout the sequence only their glances suggest the potential sexual encounter that never materializes as the two men float away like fleeting apparitions.

What this collection does best is to illuminate how Michals’ creative, genre-crossing work has influenced the history of late 20th-century photography. Aaron Schuman’s personal and engaging essay, “Lessons Learned: Three Encounters with Duane Michals,” sees in the early work of the 1960s and early ’70s a prescient vision of choreographed and narrative photography that later became vital to the genre’s place in contemporary art. Shuman correctly notes that Michals has spent the last half-century blurring the boundaries between “photography and art, between fiction and reality, between the personal and the universal, and between artwork and the artists.” But more importantly, he has “consistently redefined such boundaries in terms of his own life and his own needs, and has even pushed past such boundaries, repeatedly and resolutely exploring territories well beyond the established frontiers of photography itself.”

James Polchin teaches writing at New York University and is a frequent contributor to this magazine.