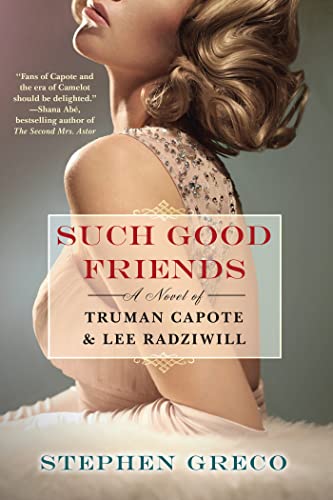

SUCH GOOD FRIENDS

SUCH GOOD FRIENDS

A Novel of Truman Capote & Lee Radziwill

by Stephen Greco

Kensington. 480 pages, $16.95

A FRIEND noticed Such Good Friends on my table and scoffed, “Candy!” Maybe, but candy can be a Mars bar or it can be Teuscher’s Champagne Truffles. Stephen Greco’s book is the highest form of confection I’ve read in years.

The premise is simple: a 21-year-old aristo, Marlene, a refugee from Castro’s Cuba, finds a much-needed housekeeper position with Princess Lee Radziwill, née Bouvier. The year is 1961, and among Jackie Kennedy’s sister’s closest pals and confidantes is writer Truman Capote. Over the years, Marlene becomes a friend, sounding board, sometime advisor, and coauthor, to Truman and Lee. She’s a close-up witness to the historical, and quite dramatic, events of several Social Register families’ lives and times. Capote is omnipresent as the wittily commenting, often instigating, diminutive author during his seemingly unstoppable ascent and then his equally steep dive into perdition. It’s all here: the marriages and divorces, the assassinations and theater failures, the Bouvier girls’ competition over billionaires, the amazing parties, the vacations in the Mediterranean, the multiple Town & Country homes, the power brokering, the astounding decors and one of a kind fashions, the high gossip and low maneuvering. There’s never a dull moment.

In a note at the end, Greco admits that “the vast majority of the dialogue is invented, but a small portion is factual, based on…” and he goes on to list all the media consulted. There are many, because, after all, these people were famous. For fame, not unlimited wealth, not even scandal, is the glucose that powers this novel. Stas, Lee’s two-decades older, socially rigid European husband, will not abide Lee going on the stage or acting in a televised film of a classy play; he’s got a reputation to protect. But she’s a modern gal and must be free to experience things, and she gets nonstop encouragement from her best friend: the inventor of the nonfiction novel, Truman Capote. Traumatized widow Jackie, the most famous woman in the world in her day, marries a man who owns his own island and has his own army, explaining the decision: “They’re killing Kennedys. My children are Kennedys.” These are situations you probably won’t encounter every day in over-the-backyard-fence conversations.

Writing a historical novel about a time of such recent vintage is a challenge, but Greco proves up to the task. He cleverly adopts a third-person “camera-on-the-shoulder” point-of-view that allows us access to the minds and motives not only of Marlene, but also of Lee and Capote. Greco’s dialogue and choices of what to put in dialogue are usually spot-on. Tiny moments—like Lee and Stas discussing some intramural Roman Catholic business surrounding Cardinal O’Connor, or Lee with Capote’s other “Swans” dishing while at Le Cirque and Caravelle, or while sunning aboard ridiculously large yachts—are rendered impressively.

Writing a historical novel about a time of such recent vintage is a challenge, but Greco proves up to the task. He cleverly adopts a third-person “camera-on-the-shoulder” point-of-view that allows us access to the minds and motives not only of Marlene, but also of Lee and Capote. Greco’s dialogue and choices of what to put in dialogue are usually spot-on. Tiny moments—like Lee and Stas discussing some intramural Roman Catholic business surrounding Cardinal O’Connor, or Lee with Capote’s other “Swans” dishing while at Le Cirque and Caravelle, or while sunning aboard ridiculously large yachts—are rendered impressively.

The three-part structure with a shorter fourth part supports the author’s focus upon Lee and Tru’s attempts to find new channels of self-expression. Sooner or later, these efforts become problematical within the little mutual admiration society. Lee’s life becomes, if anything, more class-defying, more glamorous. Even when she has to work, she finds a job as a decorator and later as Armani’s promotion director. Slowly, Marlene begins to come out of her shell, and she gets one of the prized invites to the Black and White Ball that Capote throws at the Plaza.

Meanwhile, the usually astute Capote bets on his fame and high society’s adoration to keep the pot boiling. But he can’t stop hating Gore Vidal publicly, which leads to a lawsuit and a trial in which he forces Lee to decide between family (Gore) and friendship (Capote). This is no way to treat a Princess. On top of that, he makes an authorial blunder—publishing sections of his last, “Proustian” novel, Answered Prayers, that turn out to be fatal to his social “cred.” By the epilogue, which is set in the present day, septuagenarian Marlene is alone, if in a far better place mentally and socially. And what memories!

Such Good Friends is highly readable. Truman Capote is the beating heart of this novel. As the decades roll on, it has become increasingly apparent—and ironic, after all the newsprint and media noise about Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, John Updike, Eugene O’Neill, and Arthur Miller—that midcentury American literature belongs to three gay men: W. H. Auden, Tennessee Williams, and Truman Capote.

Felice Picano’s latest book is A Bard on Hercular.