TWO MOVIES about popular music and its stars were released late last year, Bohemian Rhapsody and A Star is Born, both of which portray the tinsel and terror of superstardom.

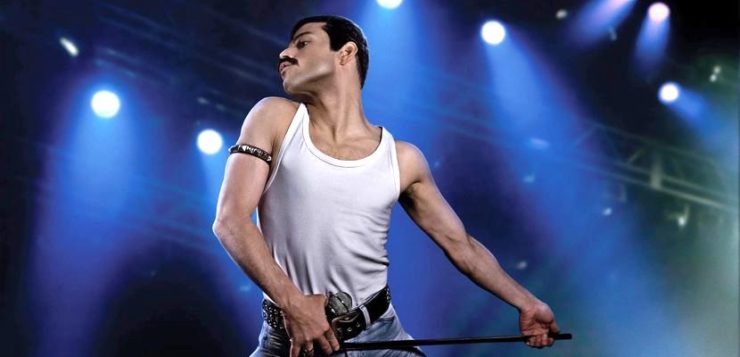

Bohemian Rhapsody is essentially a biopic about Queen’s lead singer Freddie Mercury, who died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1991. In the starring role, Rami Malek (the Emmy-winning star of Mr. Robot) struts about onstage in ballet tights and presents himself, in more ways than one, as the whole package. An additional prosthetic—buckteeth—gives Malek the singer’s famously equine overbite. Early in the film, he approaches guitarist Brian May (Gwilym Lee) and drummer Roger Taylor (Ben Hardy) in a parking lot after a gig where they’ve just lost their lead singer. “I was born with four more incisors,” he tells them. “More space in my mouth, and more range.” Now there’s a sales pitch.

Bohemian Rhapsody is framed by Queen’s performance at the Live Aid concert on July 13, 1985, before 70,000 concertgoers (including Prince Charles and Diana) at Wembley Stadium, 100,000 more in the JFK Stadium in Philadelphia, and more than a billion viewers worldwide. After three days of rehearsal, Queen’s set began just before 7 PM with Mercury seated at his Steinway. From there, the film flashes back to 1970 and the singer’s early days of obscurity. After Queen’s debut in a grungy local pub, one audience member snarls, “Who’s the Paki?” There are additional queries: when asked by his girlfriend Mary Austin (Lucy Boynton), about the meaning of his band’s name, Freddie replies: “Queen, as in Her Royal Highness, and it’s outrageous, and there’s no one more outrageous than me.” Once he finally drops his poker face and comes out to Mary as “bisexual,” she balks: “Freddie, you’re gay [and]your life is going to be very difficult.”

Below the film’s surface, there is something unsettling about how the legend of Mercury has been straight-washed for mass appeal. The original trailer for Bohemian Rhapsody drew the ire of the gay press for omitting any referenc to AIDS. Meanwhile, screenwriter Anthony McCarten compressed the timeframe in order to make the Live Aid event a kind of swan song, which it wasn’t. Mercury was diagnosed two years later, in 1987, and such a switcheroo is not just emotionally manipulative but dishonest. Even worse, the logic at work is straight: Mary’s love, like that of her Christian namesake, is a saving grace that he rejects at his peril. The love of his bandmates is likened to that of a “family,” which means that Freddie’s lover and personal manager Paul (played by Allen Leech), whom his “family” distrusts, must be jettisoned for his “villainy.”

The fact that Mercury’s fame continues to rise posthumously is ironic. Brian May told NPR’s Terry Gross that the band never enjoyed real success in the U.S. until the 1992 release of Wayne’s World, in which Wayne and Garth rock out to “Bohemian Rhapsody.” Mercury always refused to explain the lyrics to the six-minute song, but some interpret its four parts as the painful process of coming out, whereby the singer kills off the illusion of his heterosexuality (“Mama, just killed a man. … Gotta leave you all behind and face the truth”). May related the sad but clairvoyant fact that prior to his death, Mercury told May (also the film’s producer): “I suppose I’ll have to fucking die before we ever get big in America again.”

No less ironic is the fact that foot-stomping anthems like “We Are the Champions” and “We Will Rock You” were co-written by May (a doctoral student in interplanetary dust) and Mercury (a queer outcast of Zoroastrian descent), and now blare from the speakers in the biggest sports arenas on earth. Even tepid reviews could not prevent the film, with a budget of only fifty million, from earning more than that in its opening weekend. When Bohemian Rhapsody comes full circle, it soars straight to the top by recreating the Live Aid set (all 21 minutes) virtually shot for shot. Nothing short of exhilarating—close-ups, aerials, 180-degree pans—the finale was filmed first and pushed Malek to the brink of passing out. Malek, whose family is Egyptian, felt a special kinship with Mercury, who was born Farrokh Bulsara in the British protectorate of Zanzibar before his parents fled to India and eventually to London. The audio of that legendary performance was released for the first time on the Bohemian Rhapsody soundtrack and includes the 1984 hit “Radio Ga Ga.”

And speaking of Ga Ga, Lady Gaga (who took her stage name from Queen) stars as Ally and Bradley Cooper as Jackson Maine in another film that bears out essentially the same idea: fame can be nasty, brutish, and short. As Gaga told Elle magazine: “Success tests relationships. It tests families. It tests your dynamic with your friends. There is a price to stardom.” Directed by Cooper, A Star Is Born dramatizes that price and electrifies the crowd in a musical sequence every bit as thrilling as the Live Aid recreation. It’s another crash-and-burn tale of artistry and excess. In this case, the ingénue Ally’s star rises as Jackson’s falls due to drug and alcohol abuse. Another one bites the dust! While Gaga is perfectly suited to the role, the press loves a comeback and greatly overstated her performance. It’s not as if she took on Medea or Lady Macbeth, and revealing one’s natural hair color could be yet another costume. In A Star Is Born, Gaga is a pop star playing a pop star, which is no more of a stretch than diva Madonna playing diva Eva Perón in Evita.

Is there anything especially queer about A Star Is Born? Not particularly, aside from the fact that Jackson first encounters Ally after stumbling into a gay bar on drag night. He has come straight from a concert and craves just one (or five) more drinks. A bad romance ensues. Cooper, in his directorial debut, cast many of the drag queens he knew from Philadelphia. Ally is the only biological female who’s allowed to take the stage (where she sings “La Vie en Rose”). If A Star Is Born is a vehicle for its leading lady, this isn’t the first time. Janet Gaynor originated the role in 1937 (with costar Frederic March), followed by Judy Garland in 1954 (James Mason) and Barbra Streisand in 1976 (Kris Kristofferson). In the third version, Kristofferson is astoundingly flat and far less sympathetic than Cooper’s Jackson, who, in a full tailspin mode, crashes an awards ceremony when Ally is onstage, falls over drunk, and pees his pants. Kristofferson uses vodka as a hand sanitizer and says things like “Let’s go boogie!” Clearly it was time for an update.

The film’s success could not come at a better time for Lady Gaga, whose star has dimmed a bit in recent years. Since her debut ten years ago, she has won six Grammys and one Golden Globe, and knocked ’em dead at the Super Bowl. Yet the third of her five studio albums, 2013’s “Artpop,” was dubbed “Art Flop” by music critics, and a hip injury and subsequent surgery left her debilitated. Last year’s documentary Gaga: Five Foot Two provided fans with a behind-the-scenes look at her break-up with actor Taylor Kinney and her ongoing defense of LGBT rights via the Born This Way Foundation, which she founded with her mother. All told, Gaga has safely secured her status in a pantheon that includes such icons as Garland and Streisand and, for that matter, one Freddie Mercury of Queen.

Colin Carman, PhD, is the author of the newly published The Radical Ecology of the Shelleys: Eros and Environment (Routledge) and a contributing writer to this magazine.