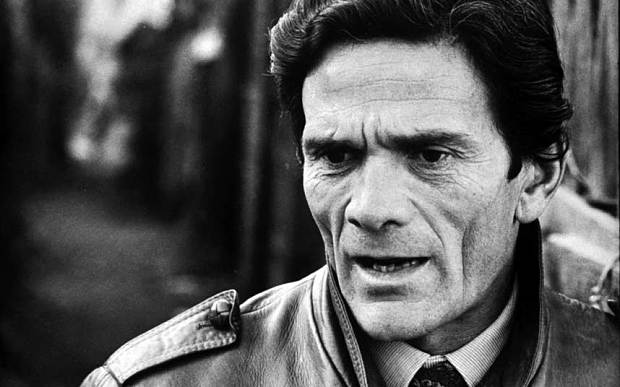

PIER PAOLO PASOLINI (1922–1975) did not actively do much for gay rights in Italy, and yet he contributed to progress inadvertently by appearing in headlines over and over again as the country’s most controversial gay person.

One reason that he didn’t do much for gay rights is that he was personally homophobic. He saw his sexual orientation as a sin, and over the years he used various pejoratives to refer to it, such as “secret and guilt-ridden,” “devil,” “terrible,” and “degrading.” Tonuti, his second lover, denied that Pasolini was gay. Even Pasolini denied his orientation in a sense. At one point he wrote: “My homosexuality … had nothing to do with me. … I always saw it as something next to me, like an enemy, never feeling it inside me.” At times, he struggled to free himself of homophobia, but never overcame it, achieving, for a while, only some comfort with hired sex.

In his youth, Pasolini fixated on a particular sexual type and romanticized his sex partners by thinking of sex as a connection with a divine, life-giving source. As he grew older, he realized that this obsession had become a troublesome psychological complex. With age, money, and fame, sex with hustlers was strictly a commercial transaction. The boys that he had once thought of as his poor brothers had transmogrified into mercenary, violent thugs that he hated.