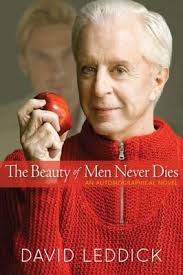

The Beauty of Men Never Dies:

The Beauty of Men Never Dies:

An Autobiographical Novel

by David Leddick

University of Wisconsin Press. 135 pages, $24.95

A FORMER ADMAN, an actor, a prolific writer, and—judging by the cover photo on his latest book—David Leddick is a remarkably well-preserved man in his eighties. He served in the Navy in World War II and danced at the Metropolitan Opera in the 1950s. These personal details figure in this “autobiographical novel,” a phrase that blurs the distinction between an author’s real life and an imagined story. Despite the ambiguity of the title, the voice that dominates the book seems to belong to Leddick rather than to a character he has created.

The narrator of these short, loosely connected chapters is an old man looking back on a life he believes has been “pointless but amusing.” What plot there is comes from the narrator’s four major romances, of which the first was with Clyde, a young sailor he met on a battleship during the War. Of the four, only the most recent of his lovers, Fenil, a Uruguayan policeman in his twenties, comes to life as a fully realized character. Leddick had hired Fenil to be his physical trainer at a gym in Montevideo, and this gives rise to some nicely erotic descriptions of the handsome, fit young man. Because Clyde and Fenil were straight, they eventually became alarmed by their sexual involvement with another man. Leddick’s other two lovers were gay, but very thinly sketched, especially the one Leddick calls “the great love of my life.”

Leddick is at his best when he writes like a novelist, setting scenes and creating dialogue. One of the longer chapters describes an interaction with Fenil in a surreal, seventy-story luxury hotel in Panama City. Fenil is returning home to their shared bed later and later each night. Realizing he is losing the young policeman, who has a son and a girlfriend, Leddick ponders earlier betrayals and failed relationships.

Aging is the great uncharted territory of gay life. How many women and men with gray hair appear in the photos for HRC promotions? Leddick boldly enters this territory, but his report on what it means to be an older gay man may not connect with a generation that’s seeking the right to marry. “I wanted romance,” he states, not a “domestic relationship.” Leddick has the money to travel to exotic locales, seek out beautiful men, and move on when passion ends—a life that may not appeal to readers for whom (gay) life means commitment to a partner, to a family, or to a community. Nor does it address the deeper experience of aging for many gay people: the gradual loss of the family of contemporaries who gave meaning to their lives.

It is when Leddick ceases to tell a story and addresses the reader in a more self-conscious, analytical voice that the book falters. Thus, for example, we get the following bit of earnest wisdom: “Perhaps those who live to be the oldest are those who have felt the least for others. They have lived untampered with and undistorted by the losses of love.” Then, too, Leddick’s concerns tend to be quite superficial: glamor, money, physical appearance. He elevates to importance the concept of “bodily collision,” when great sex happens between two people who otherwise have no interest in each other. A writer like Quentin Crisp can make the superficial profoundly entertaining; Leddick, not so much.

________________________________________________________

Daniel Burr is an assistant dean at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, where he teaches in the medical humanities program.